Less than two years after the return of the Morrison government, the predictable speculation about an early election is intensifying. Favourable Coalition polling permitting, Australians may be voting in the second half of this year.

Regardless of the date, it is worth emphasising that the result of the last election, in 2019, confirmed an enduring feature of modern Australian federal elections. Yet again, an election that didn’t change the government was decided within the 52–48 range of the national two-party-preferred vote. Conversely, in every change-of-government election since 1972 the winner has secured a two-party vote in excess of 52 per cent. In other words, a close federal election result usually means “government returned.”

Since 1977, there has only been one exception to the rule. That was in 2004, when Labor, under Mark Latham, secured a two-party vote of only 47.3 per cent, confirming the view that caucus members who voted for him to become leader shouldn’t list “good judgement” in the “key attributes” sections of their CVs.

The main point here is that outside changes of government, federal elections are rarely blowouts — at least in two-party-preferred terms — although the uneven distribution of party support can result in substantial majorities in terms of seats. The record suggests a mostly finely balanced electorate nationally (albeit with state and regional variations) most of the time.

The current distribution of seats is complicated by the presence of minor parties and independents (currently totalling six) in the House of Representatives. A glance at the pendulum for the next election reveals a challenging task for Labor, one that would require a uniform swing of around 4 per cent. But the Morrison government would lose its absolute majority with the loss of just two seats (a swing of only 0.5 per cent).

It is true that seats can move in both directions in a change-of-government election, but history tells us that there are limits. Gough Whitlam lost seats in Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia in 1972, which helped keep his victory rather narrow. Malcolm Fraser lost none of his own seats in his landslide victory in 1975, and nor did Bob Hawke in 1983. John Howard lost only the seat of Canberra (previously secured at a by-election) in 1996, and Kevin Rudd lost two Labor seats (both in Western Australia) in his substantial win in 2007.

A loss of a seat or two (sometimes because of state, regional or local factors) may be survivable, but the necessary compensatory wins can constitute a challenging task. If several seats are changing hands in both directions, it’s probably safest to bet on the government’s being returned.

Labor’s lost support in mining areas in 2019 remains a lively topic among politicians and commentators. But “mining” seats are few, and there is only one marginal Coalition seat among them: Braddon in Tasmania (scene of Peter Dutton’s expensive visit during the 2018 by-election). Beyond that, the first that would fall to Labor is Herbert (in the federal party’s consistently least successful state, Queensland), on a margin of 8.4 per cent.

Labor strategists might contend that a continuing focus on mining seats is not just about winning the ones the party failed to win in 2019 but also about retaining those pushed into the marginal column in that election. It can also be argued that in Queensland and Western Australia, where mining so powerfully defines the state economies, a perception that Labor is anti-mining may also inflict electoral damage outside mining seats — plausible, but difficult to prove.

Given the swing needed to secure majority government, Labor probably needs to hold virtually all its current seats. I lean to the view that Labor’s path to power involves winning marginal Coalition seats in suburban Brisbane and Perth rather than focusing too greatly on regional blue-collar workers, who ceased to be part of a homogeneous Labor voting bloc some elections ago. Indeed, it could be argued that the non-unionised tradesperson (with an ABN instead of a union ticket) constitutes a growing component of the Liberal Party’s base.

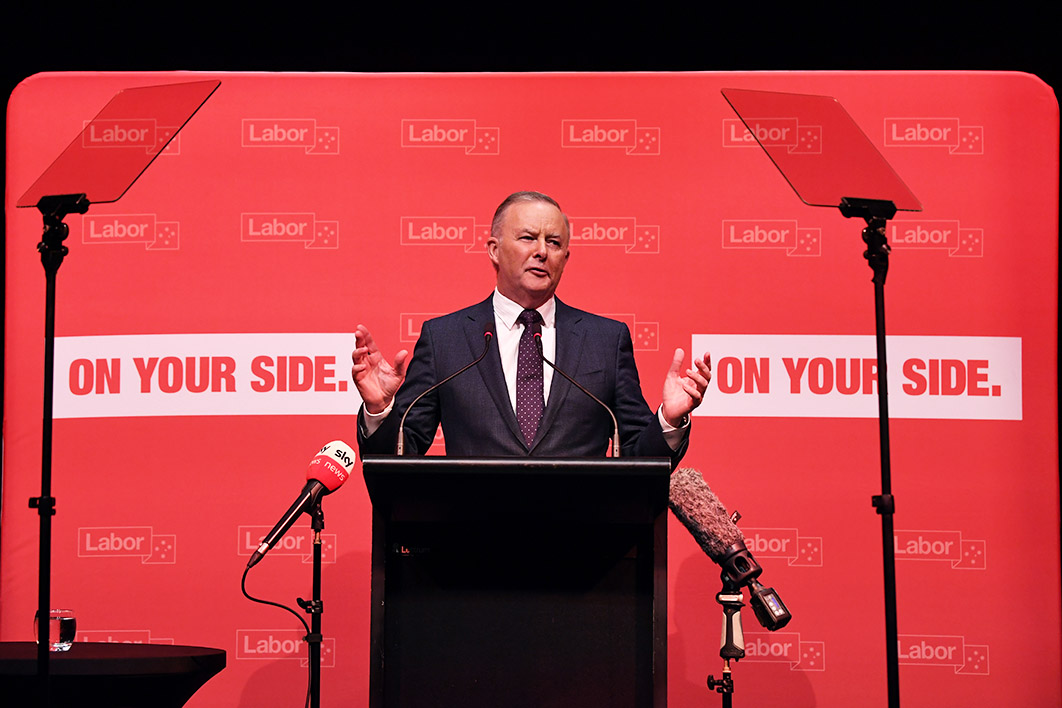

In the unusual circumstances of the pandemic, it is difficult to determine what constitutes a pass grade for an opposition leader; certainly, most of Anthony Albanese’s state counterparts have struggled to make an impact — so much so that incumbent governments have been re-elected in three Australian jurisdictions in the past six months, and who would bet against Mark McGowan in Western Australia next month?

Some might see Albanese to be doing well to have Labor polling in 50–50 territory, and might wonder about the basis of any expectation that Labor should be leading in the polls. Misbehaviour that would formerly have qualified as a political scandal has become so commonplace as to generally be of more interest to political aficionados than to swinging voters, and it can’t be expected to displace management of the pandemic as a key criterion on which the government is likely to be assessed. Clearly, Labor is hoping to use industrial relations policy to undermine the favourable impression Scott Morrison has been able to develop during the pandemic.

But some people obviously hold the view that federal Labor should already be doing better, and history certainly suggests that a change of government is usually preceded by a sustained and substantial opposition polling lead closer to 55–45 than level pegging. That was certainly the scenario that saw the election of the Fraser, Howard, Rudd and Abbott governments. Hawke took and maintained such a lead once Bill Hayden stepped down as Labor leader, just five weeks before the 1983 election. Clearly, Labor has not so far achieved such a lead.

Whether a currently unidentified new leader would do any better is uncertain, although those contemplating an alternative are entitled to remind us that, of the last five changes of government, all winners except Abbott took the leadership a relatively short time before the election, and three of the four deposed the existing leader to do so (Howard was elected unopposed). Then again, Albanese might point to Mark Latham’s successful challenge as evidence that the “change the leader” faction doesn’t always get it right. •