Oh no. Labor MPs, party apparatchiks and political pundits are again fixating on the need to “reconnect with the suburbs.” What did politics watchers do to deserve this? And more importantly, is it true?

You could tell a wonderful story about the Liberal Party’s fatal estrangement from its suburban heartland using what was once everyone’s favourite bellwether seat, Macarthur, in Sydney’s outer southwest fringe. For almost seventy years until 2016, Macarthur was held by the Liberals whenever they formed government. As recently as 2013, the party’s Russell Matheson stormed home with 54.3 per cent of the primary vote and 61.4 per cent after preferences. But less than six years later it’s very comfortably Labor-held; all the Libs could manage last year was a miserable 30.9 per cent, and just 41.6 per cent after preferences.

The party’s abysmal fortunes can be seen close up in Wedderburn, a classic middle-income Macarthur suburb that the Liberals could once take for granted. Just seven years ago, 48.4 per cent of voters there gave the party their first-preference vote; last year it was just 25.9 per cent. If the Liberals can’t win Wedderburn, how can they win elsewhere?

You see what I did there? It’s called cherrypicking. I searched the election returns to find an electorate that would fit a preconceived narrative. Most egregiously, I ignored the big 2016 redistribution that shifted the electorate into Labor territory, though that only accounts for about eight of the twenty-point two-party-preferred turnaround, and doesn’t explain any of the changed sentiment in Wedderburn (a suburb I’d never heard of until I dug it out).

How to explain the rest of the difference? Most of all, it reflects changes in the personal vote, from Matheson, the popular sitting Liberal, to Mike Freelander, a popular sitting Labor MP. The 2013 starting point was exceptionally high, coming off a very big 8.3 per cent swing that was more than twice the state figure. The Coalition’s 2013 national vote was better than its 2019 one, so all else being equal you’d expect declines everywhere. Also contributing would have been demographic changes and other factors I’m not aware of.

In other words, if you want to tell any old tale about elections and back it up with a dramatic “example” it’s usually easy to do. Lies, damn lies, statistics and all that.

Sorting the data the other way to find for the biggest tale of Labor woe gets you Capricornia in North Queensland. It’s a perfect case if you want to illustrate Labor’s low stocks among coalminers, and here’s federal MP Clare O’Neil doing just that in the Financial Review last year:

Capricornia in far north Queensland is a blue-collar regional electorate of Australians Labor strives to represent. And we used to. In 2007, 56 per cent of the people of Capricornia gave us their primary vote… On May 18, fewer than a quarter of voters in Capricornia gave Labor their primary vote.

Capricornia has been cited several times in similar fashion since the last election by Labor supporters of a blue-ish (as in Blue Labour) hue, who urge the party to cast off its post–Arthur Calwell pretensions and return to its working-class roots. (The abysmal electoral record of the pre–Gough Whitlam party goes unmentioned.) Rather inexplicably, they seem to see coalminers as emblematic of this shrinking cohort, though what people actually on low incomes think of this elevation of people earning multiples of the median wage is unclear. It seems to be part of the intra-party climate wars.

Note O’Neil’s (and others’) starting point of 2007, when Labor recorded its best national vote since the 1980s and (with a Queenslander as leader) a rare Queensland-wide two-party-preferred majority. If O’Neil had used 2004 instead, the primary vote would have been 47 rather than 56 per cent. Like Macarthur, the switch from a well-regarded Labor MP to a well-regarded Liberal National MP is a big factor in the Capricornia turnaround.

(And Labor undeniably performed abysmally in Queensland last year, particularly in seats like Capricornia, and the Adani mine played a part. Climate change is challenging for both parties, but particularly for Labor.)

The back-to-the-suburbs/mines strategy of emphasising primary vote support rather than two-party-preferred is also a sleight of hand. For most of the time after its federal introduction in 1918, our compulsory preferential voting system favoured the centre-right, but since the late 1970s, with the rise of the Australian Democrats, it has assisted Labor. The Greens, from 2001, turbocharged this dynamic, and for more than a decade now around one in ten voters have opted for Greens first, and about 80 per cent of them have preferenced Labor over the Coalition regardless of how-to-vote cards.

It’s two-party-preferred votes that win seats. And the primary vote slide is not confined to one side. The Coalition’s worst flogging since the creation of the Liberal Party, in 1983, saw it receive a higher share (43.6 per cent) than at last year’s “Morrison miracle” (41.4 per cent).

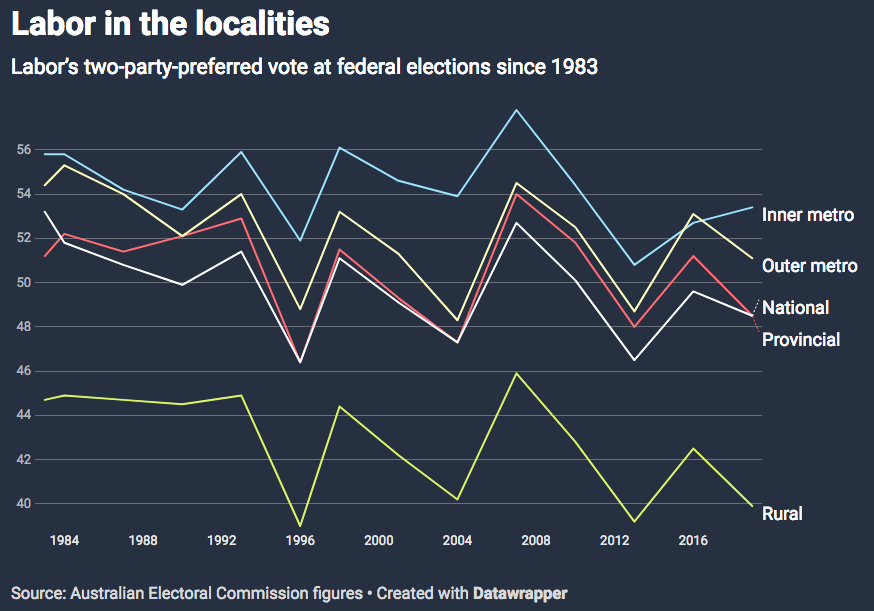

Has Labor lost the suburbs? Here’s a graph of Labor two-party-preferred votes since 1983 using the Australian Electoral Commission’s socio-demographic categories. Has the outer-metropolitan line, a proxy for the cohort at hand, been particularly bad for the party? Its lowest point across the whole period is actually 2004, when Labor set its sights on this part of the country under a leader, Mark Latham, who professed to know suburbanites intimately. Can it be that strategising with a particular section of society in mind ends up looking a bit weird, and gets you the worst of both worlds?

Oddly enough, the recent 2016 result — while far from Labor’s best outer-metro vote in absolute terms — stands out relative to the other lines. That was the year the party won another fabled “bellwether,” Lindsay, yet remained in opposition. (That election also saw outsized swings to Labor in low-income electorates, and much of the ballyhooed movement the other way last year can be seen as corrections for this.)

There’s only so much a graph like that can show. But it does suggest that a rising tide lifts all lines.

It’s not Capricornia, or Macarthur, or Wedderburn that particularly matters, it’s achieving two-party-preferred majorities among Australians. That’s what usually (though not always) wins government. •