William Cooper: An Aboriginal Life Story

By Bain Attwood | The Miegunyah Press | $34.99 | 296 pages

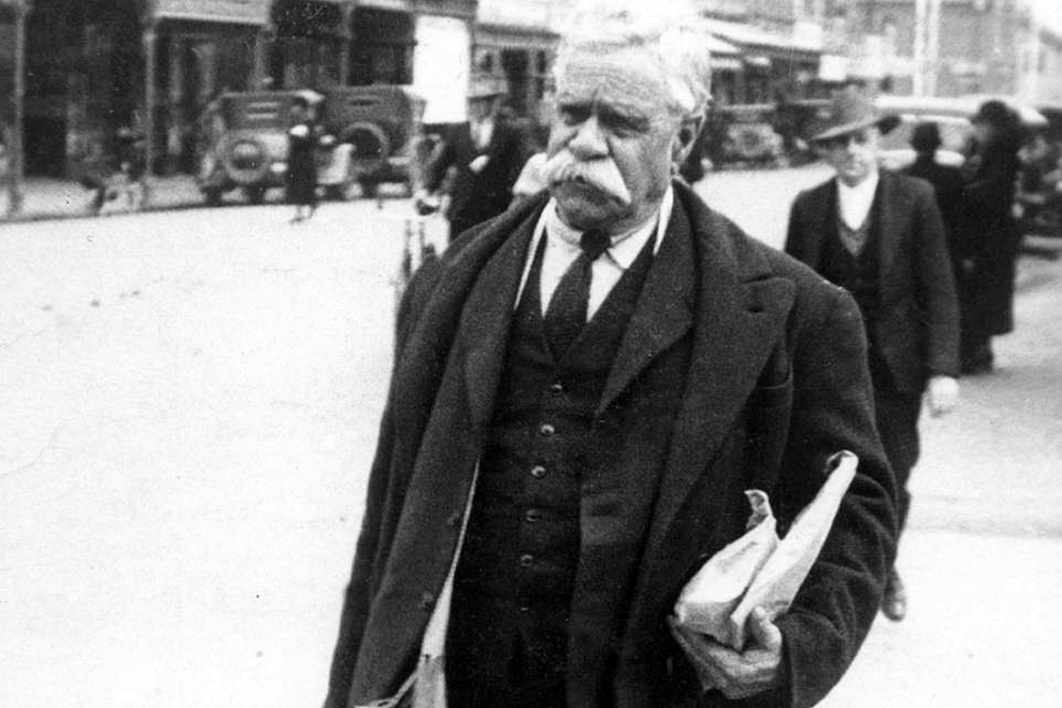

What makes a documentary trace of an Aboriginal person’s life? The question matters to historians like Bain Attwood, who believe that if “Aboriginal History” is to be more than Australian history enlarged to deal with European–Aboriginal relations then “the principal historical subject… should be Aboriginal.” The life of the Aboriginal subject of this book, Yorta Yorta man William Cooper (1861–1941), is very unevenly documented. We know a little of his childhood, very little of his working-age years and quite a lot about what he did in retirement — the final ten years of his life — when he agitated for his people’s rights.

In those last, productive years William Cooper said some things that now seem weird. On 3 December 1939, he asked prime minister Robert Menzies for legislation “granting full rights to aborigines who have attained civilised status.” What did Cooper mean by “civilised”? He didn’t mean “white”: only eight months before writing to Menzies he had complained to interior minister John McEwen about Western Australia’s policy of “absorption of aborigines into the white population” — a policy “as unfavourably viewed by us as by the white organisations.” Yet he could say (to McEwen in February 1938) that for the purposes of the White Australia policy, “the Aboriginal is white.”

And when Cooper used the word “culture,” did he mean what we now mean? On 25 November 1938 he reassured McEwen that “the Aboriginal loses his culture with the greatest facility. He as quickly acquires the culture of the superior race he contacts.” This was consistent with what he had written to the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Protection Society’s John Harris in March 1937: that “the primitive culture [is] destined ultimately to perish.” It followed from this prognosis that (as he wrote to McEwen in February 1938) “when the aboriginal people are fully cultured and are Australian in the full sense of the term you will be proud of us.”

Yet Cooper also insisted that there was something distinct and worthy about “thinking black” — a capacity attained by very few white Australians, he told Thomas Paterson, McEwen’s predecessor as interior minister, in February 1937. Cooper was proud of “thinking black” and sought to share its insights with Australian policymakers.

When we enter into Cooper’s world, as documented in the petition, the letters and the newspaper interviews of the 1930s, we must concede him a vocabulary that is very different from our own. The challenge for a biographer is to enable readers to empathise with the unfamiliar terms of Cooper’s demands for recognition and inclusion.

Historian Bain Attwood has written about Cooper before. In 2004, in collaboration with Andrew Markus under the title Thinking Black: William Cooper and the Australian Aborigines’ League, he compiled one hundred items written by or with Cooper, nearly all from the period 1933–41. This slim but rich book confronts us with the strangeness (from a 2022 perspective) of the terms in which Cooper appealed to the Australian political elite. Read alongside Michel Rose’s compilation For the Record: 160 years of Aboriginal Print Journalism (1996) and John Maynard’s Fight for Liberty and Freedom (2007), Thinking Black made it possible to construct a tradition of Australian Indigenous political thought and to tease out its thematic continuities and discontinuities.

Few have embarked on this project, however, because one of the effects of the politicisation of debates about Australia’s colonial past has been to make scholars cautious about historicising Indigenous Australians as intellectuals. It has been safer to idealise and essentialise articulate Aboriginality (“always was, always will be”) or simply leave the utterances of past Aboriginal people in the margins of narratives based on the much-quoted axiom that colonisation “is a structure not an event.” To assume that historical events do little more than enact the underlying structure of Australia’s colonisation diminishes our curiosity about contexts of Indigenous agency that were different from those of the more recent past. We have lacked ambition to understand how certain Aboriginal utterances, worded in unfamiliar ways, were pertinent to those who then spoke and heard them.

One lamentable effect of the current popularity of the axiom that colonisation is a structure not an event is that the past becomes too familiar when it would be better to allow it to be strange. Historical enquiry (enjoined as “truth-telling”) can easily become a search for ideological reassurance. It would be all too easy to keep Cooper behind the screen of our “presentism” — a revered ancestor of current Indigenous protest, but not to be too closely examined and rarely quoted.

By attempting a full biography — notwithstanding gaps in the record — Attwood shows us that the man who found his voice (and the attention of politicians and the press) on the eve of the second world war was formed ideologically by the end of the nineteenth century.

By the time Cooper was born, the Yorta Yorta had learned to adapt to colonisation by working for pastoralists; later they would become small landholders themselves. Cooper’s father (Edward or James) was a white worker; the sexual availability of women such as William’s mother was a boon to a hard life. William grew up in an Aboriginal kin group, but under the influence first of John O’Shanassy — land-owner and politician — and then of Daniel and Janet Matthews, who established Maloga Mission in 1874 on Yorta Yorta country. As Cooper became a working teenager, he sought wages outside the mission without losing sight of that secure place in which his wider kin group chose to live. Making Maloga his home from 1882, he helped petition for its extension in 1887. On that added land residents formed Cumeroogunga (“our home”).

Like most missionaries, Daniel and Janet Matthews documented their work extensively, enabling Attwood to narrate Cooper’s early adult world first through the lens of Maloga and then by describing Cumeroogunga’s dealings with the NSW government. In the 1880s Cooper’s sister married Maloga’s Mauritian teacher, Thomas Shadrach James, and we can see in Cooper’s writing during the 1930s the themes of James’s teachings to the Yorta Yorta in the 1880s: “to embrace the opportunities that Christianity and civilisation (as [James] saw it) had to offer but also to assert their rights as British subjects.” In 1881 and 1887 Maloga folk also demonstrated a form of political action — the petition — that Cooper was to take up again in 1933–37.

Cooper committed his life to the Christian God in 1884, as one of many converts in what historian Claire McLisky calls the Maloga Mission Revival. For the Yorta Yorta, Attwood writes, Christianity “was a powerful framework to make sense of their oppression, endure it and raise their voices against it.” God remained one of the two higher authorities against which Cooper — a lifetime Bible reader — would judge the flawed behaviour of Australian Britons; the other was the British Empire, with its promise of liberty and progress under the rule of law. In 1937 he assured John Harris that “the Aboriginal is more British often than the white.”

Attwood shows that people living at Maloga and Cumeroogunga had the chance to find out that the wider world was white-dominated. In 1886 the Fisk Jubilee Singers — evangelical Christian African-Americans and advocates for the rights of former slaves — visited Maloga. Their stories of the vicissitudes of Reconstruction in the United States must have resonated. Cooper’s awareness of non-white peoples was nurtured also by his visits to New Zealand (as a shearer) and by his reading. He was not only a trade unionist (as a member of the Shearers’ Union and Australian Workers Union) but also — we suppose — a reader of the labour movement press. He was to learn how, under British authority, “cannibals” in Fiji had advanced, Māori could elect four members of parliament, the government of Canada was paying attention to the “Eskimo” and, in the 1930s, “native affairs” exercised the imagination of white South Africans.

While white power over non-white people was a global phenomenon, the struggles against it — for Cooper, at Maloga and subsequently at Cumeroogunga — were local and particular. The narrative drive of Attwood’s biography is that the Yorta Yorta (with Cooper himself sometimes in view) were in constant negotiation with various forms of white authority, at times assisted by white champions — and not without victories. On this he gives much interesting detail.

Cooper retired to the inner-Melbourne suburbs of Footscray and Yarraville, where he lived on the aged pension. He recruited allies a generation younger than himself, including his nephew Shadrach Livingstone James (1890–1956), the “Christian communist” Helen Baillie (born c. 1893), Anna and Caleb Morgan (birth dates not given), Arthur Burdeu (born 1882) and Doug Nicholls (1906–1988). This milieu was Labor-affiliated and Christian. By February 1936, they had formed the Australian Aborigines’ League, or AAL. They believed that the civilisation that had colonised Australia had the potential and the obligation to treat Aboriginal people more fairly, and to do more to “uplift” them.

Attwood lists four connected ideas of the AAL that may or may not mesh with the outlooks of many who will read this book. First, that the rights they sought “were not so much an entitlement as something to be earned.” Second, that the demand for justice was more pressing for “civilised Aboriginals” (who were to be entrusted to guide the elevation of those still “myall”). Third, that differences of capacity were what mattered, as there were not any intrinsic differences of “race” or “colour.” Fourth, that Aboriginal people were of the same nature as white Australians. Such precepts may chafe some contemporary versions of identity politics.

Attwood’s account concludes by reminding us how high-handed, self-confident and paternalistic were the political elites of Australia in the 1930s. In the dismissive and deceitful treatment of the AAL’s petition to the King, in the self-congratulatory “foundation” celebrations of John Batman (1937) and Arthur Phillip (1938), and in the reluctance of the NSW government to discipline the bullying Cumeroogunga manager (1939) we see good reasons for Aboriginal people’s lasting anger. A self-satisfied Australia lacked the humility and perspicacity to test itself against the standards of British Christian civilisation on which Cooper and his colleagues were insisting. •