After news of the Japanese surrender reached Australia on the morning of Wednesday 15 August 1945, the brief announcement from prime minister Ben Chifley on national radio was taken up by wailing sirens, clanging trams, train whistles, car horns and church bells in cities and towns across Australia. “Let us remember those whose lives were given that we may enjoy this glorious moment,” said Chifley, “and may we look forward to a peace which they have won for us.”

Celebrations in Canberra followed the pattern – office workers downed pens, shops shut, schools closed and crowds congregated in the Civic Centre to sing and dance. Although beer supplies ran out during the afternoon, the festivities resumed at the Manuka oval and continued long into the evening. On the following day Chifley and members of the diplomatic corps attended a thanksgiving service at the War Memorial.

The staff of the Department of Post-War Reconstruction were not present at the service because the director, H.C. Coombs, had called a meeting for early that morning to consider their most urgent tasks. One of those summoned was Trevor Swan, the young economist who had developed the statistical procedures that guided the War Commitments Committee’s deployment of manpower. Another, still younger, was Noel Butlin, who had been taught by Swan the year after this gifted but highly strung prodigy graduated at Sydney with the university medal.

Butlin would recall how a chain-smoking Swan prowled Coombs’s office that Thursday as he enumerated the concatenation of circumstances created by the abrupt end of hostilities and the measures needed to deal with them: “demobilisation, protection against immediate displacement consequences, training and retraining, expediting readaptation of factory production, restoration of infrastructure and housing, capital issues control, monetary and fiscal measures to cope with expected inflationary pressures.” The others present – Coombs, economists John Crawford, Gerald Firth and Arthur Tange, political scientist L.F. Crisp and Butlin himself – contributed to the discussion, “but it was undoubtedly Trevor in the starring role” and by the end of the day “measures to deal with the immediate transition from war to peace were in place.”

As these public servants worked out the sequence of steps needed to throw the vast machinery of the war economy into reverse, the country’s leaders moved to dampen expectations. Chifley warned that the sudden ending of the war so much earlier than expected presented both the government and the people with a challenge. Although the steps necessary to effect “a smooth and rapid transfer from war to civil production” had been worked out, the pace of their implementation would depend on ready cooperation and goodwill. A broadcast that evening from the governor-general reiterated that the tasks of reconstruction required Australians to “work hard together for the good of all.” “Let no one suppose,” he warned, “that we can slacken now, or that peace will bring a utopian state of rest and benefit for all.”

Expectations were high, and understandably so since the government had built them up as an inducement for the sacrifices it demanded. Now, after six years of effort, it was anticipated that peace would allow normal patterns of life to be resumed in the improved circumstances the victory made possible – better homes with superior amenities, more secure and rewarding jobs, greater social protection and a higher standard of living in a prosperous and progressive society. Chifley had good reason to ask for patience since he knew the changeover would be difficult. The governor-general, who had only come to Australia at the beginning of 1945, was astonished by the country’s backwardness and neglect.

While Australians were celebrating and even before the economists gathered at Acton to expedite the plans for reconversion, Coombs had chaired a meeting of the Standing Committee on Demobilisation to bring forward the scheme for discharging members of the armed services. This committee reported directly to the War Cabinet and included representatives of the three armed services, but the Department of Post-War Reconstruction guided demobilisation from its inception. Despite criticism from the parliamentary opposition, there were compelling reasons for having the department direct such a complex undertaking: an orderly return to civilian life bore directly on the plans for industry, employment, housing and much else.

The scheme cabinet approved in March 1945 envisaged a discharge from the forces at a rate of 3000 persons per day, a rate that was expected to facilitate their absorption into employment. The order of the discharge was to be determined by age, length of service and family responsibilities: servicemen would be given two points for every year of age at enlistment and two points for every month of service, or three for those with dependants, while a servicewoman (who was assumed to have no dependants) would receive three points for every year of age and one for every month of service. After ready reckoners were distributed in camps and bases to help recipients calculate their tallies, a war correspondent on the island of Morotai described how “points scores and probabilities of departure are studied and discussed like form guides.”

Coombs and his department had to devise a process that combined various formal requirements with assessment of eligibility for benefits and assistance. They did so by creating an integrated dispersal centre in each of the state capitals – a vast establishment with a series of booths staffed by representatives of the various specialist agencies, and behind them typing pools where the necessary forms were completed and documents produced. The centre at the Sydney Showground had 140 doctors and more than 1000 other officials, with a telephone switchboard of 250 lines to speak to prospective employers. Progress along this human assembly line began with a health check and ended in the issue of a final service pay cheque along with a rail pass back to the place of enlistment, street clothing and a tobacco allowance. If the assembly line made for efficiency and expedition, the human dimension demanded a sensitivity to individual circumstances not normally associated with bureaucracy.

The dispersal centres were still being set up when Japan surrendered and the earliest they could be made ready was the beginning of October. The government therefore decided that demobilisation would proceed in stages: an initial reduction of 200,000 from 1 October to 31 January in the current strength of 554,000 men and 44,000 women, and then a further 200,000 by 30 June 1946. The delay was only six weeks but it exacerbated the frustration of troops waiting to return to prewar occupations and employers who were keen to restart them. The cabinet had already begun an early release from the services for men with five years of service and others on compassionate or occupational grounds, but these discharges were suspended to allow preparation for the general demobilisation. The opposition accused the government of bungling the process, the deputy Liberal leader Eric Harrison even alleging that the government had postponed it so that trade unionists put off from war industries could find jobs first.

The delay was particularly irksome for the 244,000 Australians stationed abroad. Lieutenant Clive Edwards, who volunteered for the AIF in 1940, served in the Middle East, married while on leave in Perth and was now on duty at Morotai, assumed he had the points for an immediate discharge. His platoon, “doing absolutely nothing all day and every day,” was to return in September but then learned that all available shipping was needed to transport prisoners of war back to Australia and occupation troops to Japan. He wrote home to vent his frustration: “Again it appears that our government has made wild schemes which they have no hope of fulfilling.” As Christmas approached, 1500 soldiers at Morotai marched in protest against the delay.

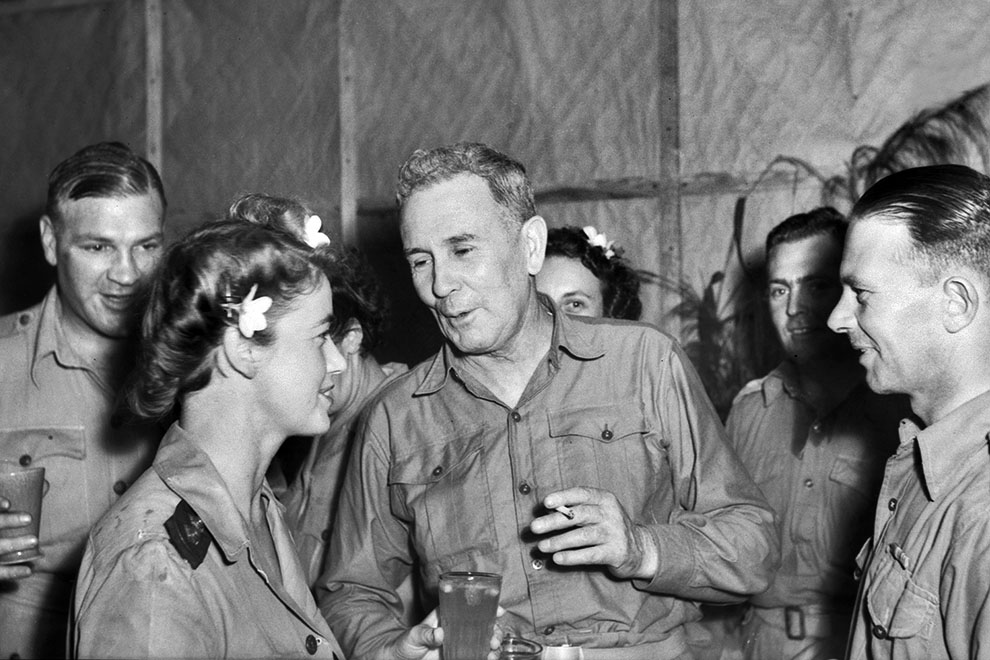

“The times ahead will be difficult for the Party,” the Melbourne barrister and Labor insider John Vincent Barry wrote to his Sydney counterpart, Bill Taylor, two days after the end of hostilities. With shipping under American and British control, the repatriation of military forces serving abroad would inevitably encounter “irritating delays.” Since the press was likely to distort the difficulties and exacerbate resentment, radio provided the best means of explaining the task and Barry urged Taylor to persuade his friend Chifley to use it. The prime minister, who had a horror of the airwaves and declined to make a broadcast, could nevertheless see the need to allay discontent and flew to New Guinea and the Solomons to spend Christmas with the troops. It was characteristic that he spurned formality, simply sitting himself among soldiers in the messes he visited and saying, “I’m Chifley, who are you?” and just as characteristic that he threatened heads would roll if publicity was given to his trip.

“Is the federal government doing enough for ex-servicemen?” Australian Public Opinion Polls asked in July 1946, nearly a year after hostilities had ended. Fifty-nine per cent of the respondents answered no. There was no lack of publicity given to the re-establishment of service personnel: 600,000 copies of the fifty-six-page booklet Return to Civil Life were produced, along with additional publications on training, re-employment, housing, pensions and other benefits. The government provided special funds for an “enlightenment campaign” aimed at “removing ignorance on the part of civilians,” countering “uninformed criticism” and helping the families of servicemen and women understand what was being done for them. John Dedman, the postwar reconstruction minister, broadcast frequently, albeit with some acknowledgement of the difficulties: “No plan of demobilisation will ever meet with the approval of everybody.” Coombs appeared on a weekly ABC radio program to answer queries from ex-servicemen and women about their entitlements – and was accused by Eric Harrison of pushing the government line.

Demobilisation went remarkably smoothly. After problems in Brisbane caused by the need to complete the centre at Redbank, a steady stream of men and women passed through all six dispersal centres and out into civilian life. The goal of 3000 discharges a day was soon exceeded and by the end of January 1946 more than 249,000 had been released. With the completion of the second stage in June 1946 the number approached 450,000 and 80 per cent of all those in uniform at the ceasefire were back home by the anniversary of V-J Day.

Yet grumbling continued, fanned by instances of neglect that were taken up by the Returned Sailors’, Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Imperial League of Australia, or RSL, and publicised in scandal-rags such as Smith’s Weekly. Woe betide those with ministerial responsibility. The dutiful army minister, Frank Forde, who rejected all pleas for early release from the army, lost his seat at the 1946 election, as did the hapless repatriation minister, Charles (“Hoar”) Frost. His successor in the portfolio, Claude Barnard, a courtly politician of the old school, was turned out in 1949.

One reason for the discontent was that many who completed service were not ready to make the transition to civilian life. As they arrived back in Australia they were given leave to return to their family homes for a “living out” period so that they could begin the adjustment and make plans for the future before reporting to the dispersal centre. Some struggling with the traumatic effects of fighting were unwilling – or unable – to respond to what was on offer. Others simply wanted a longer break. A journalist spoke to soldiers of the 7th and 9th Divisions, who were among the first to return from New Guinea and Borneo, and found that “everyone’s first plan is to get a holiday.” Sergeant G.M. MacFarlane said that “for a while all I want is three good meals a day and a good bed”; then he would return to his job at a gas company “but it will take a bit of getting used to.” Sergeant Norman Hadley intended to find a new job but was in no hurry: “I’m not going to begin working again until after Christmas.” Warrant Officer Charles Scott stated simply, “I’m going to have a good time first.”

The women were more practical. When a journalist asked members of the Women’s Army Service passing through the Redbank centre in the middle of November about their intentions, one replied, “To hunt me a man.” Many anticipated marriage and planned to undertake training in domestic skills, but others sought further options. Hence Miss M.V. Hibdon would take a short holiday before beginning a part-time course in dressmaking. Private Heather Gleig-Scott thought she would resume her job as a telephonist but learn dressmaking and typing in case she wanted a change. Sergeant M. Shepherd from Cairns had been a clerk but life in the army had given her “a new outlook” so she would “find a job where she could move around and meet people.” Another army woman used to be a governess but “the army has cured me of that” and she proposed to complete her matriculation and become a librarian.

Notwithstanding their apparent readiness to get on with life after the war, the ex-servicewomen aroused concern. They had left homes and set aside domestic duties to undertake new tasks, an experience that broadened their horizons yet enclosed them in military discipline. One concern was whether younger women would be ready for household management and how they would cope when released from the routines of institutional life. “Leaving the WAAF was rather like leaving school,” one who enlisted as an eighteen-year-old recalled; “my life in the service had been completely organised, there was no need to worry about what to wear, what to eat, where to live – it was all laid down for us, all that was necessary was to do as we were told.” A further concern was whether these women would want to return to domesticity, for their service entitled them to retrain and pursue civilian careers.

Conscious of these divergent expectations, Coombs decided quite early to appoint a senior officer to guide the re-establishment of ex-servicewomen and “assist in reconstruction matters affecting women generally.” His extensive search led to the appointment of Kathleen Best as assistant director of the Re-establishment Division of his department. Best was a matron in the army nursing service, decorated for her courage during the evacuation from Greece, and subsequently the adjutant-general of women’s services at military headquarters in Melbourne.

Kathleen Best in 1944, shortly before she took up duties with the Department of Post-War Construction. Australian War Memorial

A newspaper profile at the time of the appointment in August 1944, when Best was still in her mid thirties, described her as an enthusiast with a “quiet, yet forceful personality” – and she would need those qualities as she pressed for recognition of the special needs of women. Like Coombs, she thought that women should be able to choose whether they wished to pursue employment or leave the workforce. In either case, she stressed the assistance they would need to help them cope with the tasks of adjustment to civilian life. If they wanted to retrain, they should enjoy the same entitlements as men. If they chose to become mothers, then that vocation needed no less support.

The difficulties of securing support are illustrated by the proposals Best took to an interdepartmental meeting in early 1945. It was called by Coombs to consider “The Problems Concerned with the Re-establishment of Women and the Needs of the Community,” and included female representatives of the departments of Social Services and Health, with a mixed team from the Manpower Directorate and two men from Treasury. Best wanted retraining and assistance for women in their domestic roles, with special support for new mothers. As she explained the need for domestic aides, day nurses and emergency housekeepers, one of the Treasury officials observed that the field “apparently had no boundaries at all,” and Treasury’s resistance stiffened in the absence of the director-general from subsequent meetings. Coombs wrote to his minister in June to recommend that this expanded range of services be raised at the next Premiers Conference. Treasury informed him that Chifley would not do so. Re-establishment stopped short of the home.

The fear of unemployment had lain dormant during the war. It revived at war’s end, and with it the memories of the humiliation and hardship that had soured the 1930s. A poll conducted in September 1945 asked Australians what they thought about the prospects of employment “in the next few years”; only 31 per cent expected there would be jobs for all, with 39 per cent anticipating some unemployment and 28 per cent fearing it would be extensive.

The fears proved groundless. Of 435,000 demobilisation forms collected up to June 1946, 336,000 recorded immediate placement in employment. Another 57,000 had deferred placement, while others were training, did not seek work or were prevented from doing so by disabilities. Just 22,000 of those wishing to rejoin the workforce were not placed within a fortnight of discharge and it was clear that the great majority of them had since found work as only 6800 persons were on unemployment benefit. It was the same with the war workers. Anticipating that as many as 60,000 of these would be displaced, the government provided a special transition allowance to supplement their unemployment benefit, but the numbers claiming it were negligible.

Far from a surplus of labour, there was a shortage – the Commonwealth Employment Service recorded unfilled vacancies for 22,000 men and 31,000 women in June 1946. While the shortages included some types of skilled labour, they were most pronounced in manual occupations that called for “heavy and unpleasant work.” In the case of men, these included mining, building and construction, and the production of building materials such as bricks, tiles and timber; apart from the consequences for the housing program, the short supply in these basic industries created bottlenecks in the rest of the economy. The vacancies for women were in textiles, food processing, laundries and other traditionally female occupations.

The shortfall of women was greater because they were leaving the workforce. In the last year of the war there were 745,000 in civilian occupations and 46,000 in the forces. Two years later the number employed had fallen to 639,000. The reasons for withdrawal are deceptively obvious. Those who had earned good wages in munitions factories were not prepared to work for much lower ones in textile mills and canning factories. Those who came out of uniform and wanted to work were looking for more attractive options; office duties, hairdressing, dressmaking and catering were popular choices and the number of female working proprietors increased. Besides, there were powerful expectations that women should make way for men to resume their customary role as breadwinners.

But the testimony of those caught up in the change both confirms and complicates these explanations. A West Australian study found that while women undertook war work as a patriotic duty, many were only too glad to give it up. One munitions worker recalled that she was travelling to her morning shift when she heard of the Japanese surrender: “I went down to workshop and I said ‘that’s that!’… I could think of nothing better than not having to go to work.” Full employment for men did not prevent such women from earning wages; rather, it obviated the need for them to do so.

The reluctance of servicewomen to enter the civilian workforce was especially marked. Writing in the army newspaper Salt of her conversations on the subject, a correspondent said that “the majority intend that Home Sweet Home will be their post-war job.” A WAAF declared she was “breaking her neck to get out, get married and have children. And most of the girls in my unit feel the same.” Only a small minority of the 50,000 women who passed through the discharge centres took advantage of the centrepiece of the government’s re-establishment program, vocational training.

Despite its prosaic title, the Commonwealth Reconstruction Training Scheme, or CRTS, is recalled fondly in the memoirs of the war generation and still appears in obituaries of those who went on to notable careers. It is rightly hailed as a device that unlocked the talent of many who could not have gained a higher education without it. But the 38,000 men and women who commenced university courses under the CRTS made up only a small portion of the trainees – the great majority pursued vocational training in industrial trades. That program provided 230,000 ex-service personnel with training but it was beset by difficulties, with serious consequences for the supply of skilled labour on which the government based its plans.

The CRTS was designed to be open to all who had enlisted before their twenty-first birthday and served for at least six months. Applicants would be assessed for their capacity to undertake the course and its suitability. Those accepted would receive free tuition and a living allowance for up to three years, with an allowance for travel expenses and supplementary allowances for books and equipment.

From the outset, there were arguments over the conditions of eligibility, the methods of selection and the allowances. The Ministry of Post-War Reconstruction would have preferred the CRTS to include workers in war industries; though Treasury blocked their inclusion, it was opened in 1945 to merchant seamen and members of the Women’s Land Army. The rules of selection were formulated to give the ministry maximum discretion, which it used generously – very few members of the armed services with a genuine interest were turned away. The schedule of allowances made provision for married men (at ninety-six shillings a week it was the same as the basic wage in 1945) but the lower rate for women (fifty-five shillings provided they were not living at home) worried Coombs. He convened a special meeting of the committee at which senior officers of the women’s services declared the amount was inadequate, but was unable to win parity with men until November 1945.

The design of the CRTS left unresolved differences of purpose. Was it a benefit owed to those who had served, and if so should it be provided sparingly or generously? Or was it a form of training to serve national objectives that should override the preferences of beneficiaries? Was it an instrument of re-establishment or reconstruction? These questions found one set of answers in the universities, another in the trade schools.

Those who nominated for university study were able to enrol in the course of their choice – arts was the most popular, followed by economics, engineering, law, science and medicine – and commence (or resume) with minimal delay. Others who demonstrated aptitude could complete their secondary education before enrolment, and a smaller number was allowed to undertake postgraduate study here or overseas. Some 33,000 men and 5000 women commenced university studies under the CRTS and more than two-thirds of them completed degrees or diplomas.

Even though the demand was far higher than expected, there was no attempt to restrict enrolments. Moreover, the Universities Commission interpreted the principles of selection liberally. It was a training system, so the test was whether there was a vocational demand for graduates with the qualification that the course of study provided, but without judgement of its utility or any reference to workforce priorities. More than 3000 CRTS university trainees studied music (most of them part-time) and nearly 800 theology (almost all full-time). The CRTS provided four of the country’s six Rhodes scholars for 1949: an agricultural scientist, a linguist, a historian and a theologian.

Technical training was the troubled arm of the CRTS. It was conceived from the outset as meeting the needs of industry and used subcommittees made up of employer and union representatives to determine the numbers required in particular trades. Initial estimates were that between 60,000 and 80,000 ex-service personnel would seek full-time places and they were to be trained until they achieved a level of proficiency that would enable them to begin work and then complete their course by night study. The state technical colleges would be expanded through a Commonwealth building program and supplemented with additional facilities at former munitions factories.

The plans went quickly awry. In the first year there were 63,000 applications for full-time and 105,000 for part-time technical training. The technical colleges had their own training obligations and could offer only limited space; the additional buildings remained unbuilt; the Munitions Department insisted that its factories were to be handed over to private enterprise; and there was a lack of instructors, textbooks and even tools with which to run the classes. In contrast to the university scheme, those who applied for technical training waited months for selection, some for over a year before a place became available. More than a quarter of those who were accepted withdrew before commencement and a high proportion dropped out before completion.

The problem was exacerbated by arguments in the industrial subcommittees. Still dubious that full employment would last, some unions feared that the employment of trainees with part proficiency (the employer paid that proportion, the government made up the rest of the wage) would undermine the apprenticeship system. Some employers preferred to recruit fully trained hands. Since both parties had to agree on the CRTS intake, several of these subcommittees ground to a halt.

“The trainee scheme has broken down,” alleged Eric Millhouse, the national president of the RSL. His organisation was a persistent critic of the CRTS, its demand that the scheme be run by a dedicated ex-service authority in stark contrast to Dedman’s insistence that training was a vital component of reconstruction. So too Chifley’s reply to Bob Walshe, the president of the New South Wales Council of Reconstruction Trainees, which was agitating in the increase of allowances: “the CRTS was not a reward for service but an integral part of the Government’s policy of full employment.” But if that was the case, asked Walshe, why were the trainees put on “a pension scale” of allowances? Walshe campaigned for parity of the allowance with the basic wage, which increased to 106 shillings a week in 1946 and 129 shillings by the end of 1949, when the maximum training rate for a married couple with two children was 116 shillings and subject to income tax.

Although we still lack a proper analysis of the CRTS’s beneficiaries, the limited studies that are available suggest a strong appeal to former private school boys of modest means who might otherwise have settled for office jobs; half of a sample of 166 former students of Trinity Grammar School in the middle-class Melbourne suburb of Kew undertook university studies under the scheme. Even so, substantial numbers who had attended government schools also took advantage of the unprecedented opportunity. The Universities Commission supported them with additional tuition and advice from guidance officers, and their academic performance was better than that of the other students.

Australia was not alone in assisting those who had gone into uniform to obtain higher education. The United States had its GI Bill, and similar arrangements were introduced in Britain, Canada and New Zealand. In each case they brought substantial enlargement of university enrolments, setting the universities on a course of growth that would continue for the next quarter-century. They opened up new possibilities for men and women from families with limited means who had previously been shut out of further study. And in doing so they augmented their countries’ professional skills, with lasting results for economic development and national life. •

This is an edited extract from Stuart Macintyre’s latest book, Australia’s Boldest Experiment: War and Reconstruction in the 1940s, published in June by NewSouth.