Our Man Elsewhere: In Search of Alan Moorehead

By Thornton McCamish | Black Inc. | $39.99

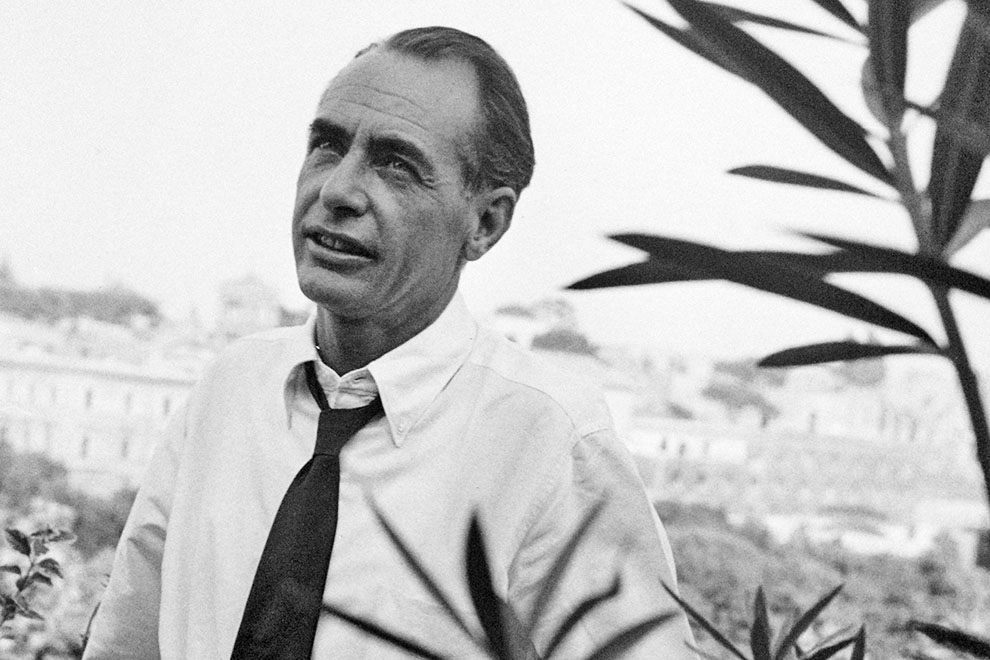

If you were asked to name the best Australian writers of the twentieth century, whose names would spring to mind? Well, of course, Patrick White, Xavier Herbert, Tom Keneally, Manning Clark, Christina Stead, Clive James, Donald Horne. I wonder how many of us would think of Alan Moorehead – war correspondent, historian, author of some twenty-two books, and perhaps the most famous Australian writer of his day? Before I read Thornton McCamish’s wonderful new biography, I doubt if I’d have thought of him myself.

At the height of his career, Moorehead was not only an acclaimed writer: he was a rich and prosperous one. He owned a beautiful house on an Italian hillside and a pied-à-terre in London. He sent his sons to Eton and could afford to knock back an offer of £30,000 a year – a fabulous sum in those days – to continue writing for Lord Beaverbrook’s Daily Express. In McCamish’s words: “In London he was considered a major author, and he was certainly the best-known Australian writer in America.” According to the Washington Post, he was “one of the finest writers in the English language.” A critic in the Times praised “the strain of haunting lyrical beauty” in his work. And Clive James, no mean wordsmith himself, considered him “a far better reporter on combat than his friend Ernest Hemingway.”

On combat. Perhaps that’s the problem. Moorehead was seen as a specialist in a narrow field. Yet the range of his experience was dazzling. In one twelve-month spell in the 1940s, he travelled (by his own estimate) almost 50,000 kilometres across Africa and the Middle East. By 1943 he had flown on bombing raids over Eritrea and the Red Sea and covered conflicts and upheavals in Kenya, Somalia and Abyssinia. He interviewed Gandhi and Nehru in India and flew the length of Africa in a flying boat – all part of what McCamish calls his “focused wanderlust.” He was an international celebrity, hobnobbing with the likes of Truman Capote, Evelyn Waugh, Ingrid Bergman, Elsa Maxwell, Nancy Mitford, the composer William Walton, and countless others. William Shawn, fabled editor of the New Yorker and a great enthusiast for Moorehead’s work, was a loyal mentor and friend.

Among Moorehead’s best-known works were Gallipoli, his classic account of the disastrous Allied invasion (“masterful,” according to Germaine Greer), and his bestselling books about nineteenth-century colonial exploration, The White Nile (1960) and The Blue Nile (1962), critically acclaimed in their day and still in print. Biographies of Montgomery and Churchill, a history of the Russian revolution, novels, memoirs, countless articles in prestigious magazines flowed from his pen. Perhaps the only Australian journalist with a career to compare with Moorehead’s was Keith Murdoch, another boy from Melbourne who fought his way to the top in Fleet Street and made a name for himself at Gallipoli.

So why is Moorehead so little remembered? Have we lost that schoolboy sense of adventure, the zest for travel and storytelling that drove Moorehead and energised his prose? Perhaps. But there’s something more. As McCamish makes clear, he was a deeply conflicted man. He loved writing about death and carnage on the battlefield but was haunted by “the infinite horror” of war itself. He was a brilliant journalist for whom journalism was never really good enough: all his life he longed to be a “serious writer,” to produce a classic novel at a time when successful fiction (in Robert Hughes’s words) was “the ultimate test of a writer’s prowess.” More than that, he never felt truly Australian, preferring to live in Italy or London and sharing Nevil Shute’s view that “young Australians found their country narrow and stultifying.” “I did not feel,” he wrote during one of his spells of despondency, “that I really belonged to Australia at all.”

This is no conventional biography. Those have already been written, notably by Tom Pocock, whose 1990 book is a standard reference. McCamish’s approach was to revisit the places Moorehead had seen and written about: “My idea was that if I followed the thread linking Moorehead’s work to the places where he wrote them, I might, with some intuitive effort, some narrowing of the eyes, get a fuller imaginative sense of what his world looked like.” He succeeds beautifully: Our Man Elsewhere is crammed with anecdote and shrewd observation, with the kind of detail and ruminative digression that conventional biographers might consider trivial or irrelevant. Although Paris yielded little in his search, in the Sicilian town of Taormina McCamish felt “as close as I’d get to the ordinary reality of Moorehead’s wartime – the boredom, the uncertainty, but also his feeling of being thrillingly alive at a moment when history was out of its cage.”

Read this extraordinary book and I guarantee you’ll want to revisit The White Nile, Cooper’s Creek, The Fatal Impact and No Room in the Ark, a loving study of the beauty of African wildlife. Moorehead himself comes across in all his complexity and charm: “the lonely and unhappy man” described by Manning Clarke; the compulsive womaniser; the pathologically nervous public speaker; the self-doubting perfectionist whom fellow journalist James Cameron described as “the best of us all.”

Moorehead married Lucy Milner, fashion editor of the London Express, in 1940. Despite Alan’s serial infidelities, it was a close and enduring marriage. In 1970 Lucy published the autobiography of her husband, A Late Education, put together from his earlier writings (and I was reminded that Anne Brooksbank, the playwright, is working on a similar project about her husband, Bob Ellis, who died in April). Lucy’s book was an act of love. There was no way Moorehead could have written it himself. In 1966 he suffered a stroke that left him half-paralysed and barely able to speak for the last seventeen years of his life.

It was an unbearably sad ending to a life of great excitement and vitality. Our Man Elsewhere is such a good book that I’m hard put to find anything wrong with it. The editors and proofreaders at Black Inc. have done an excellent job, and McCamish, whose name is new to me, may be as good a writer as Moorehead himself. But somewhat to my relief – since all journalists love spotting mistakes in the work of others – I found a small error. When Alan first earned a regular byline on the Express, his name was more than once misspelt as “Moorhead.” Surely no book about a great journalist could get his name wrong! But on page 145 of Our Man Elsewhere the same error creeps in. Moorehead is “Moorhead.” Oh dear. But as the man himself would have said, in his quietly unassuming and calmly fatalistic way, these things happen. •