A GOOD twelve months out from the likely election date and the Tony Abbott–led Coalition, despite some recent slippage, is still tracking towards victory. But whether an Abbott government will rule or merely govern will hinge on the Senate results, and they defy predictability for a range of reasons.

Among the many possible outcomes are a Coalition majority (though that seems unlikely), a Coalition minority with crossbench support, and a composition similar to what we have now in the Senate, with the Greens holding the balance of power. And this last possibility raises what is to me a very pertinent, but still unasked question: how would an Abbott government – and especially Abbott himself – deal with the Greens?

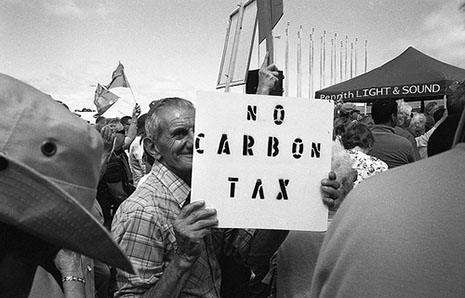

Ideologically, socially and politically, Abbott and the Greens are as far apart as far apart can be. Their common ground on any question, save for the scuttling of the Rudd-inspired emissions trading scheme (though for entirely different reasons), is so close to zero that it doesn’t matter.

Without a majority and without sufficient support on the cross benches, governmental paralysis would be very much the order of the day in cases where Labor and the Greens vote together against Coalition legislation. And the constitutional remedy of an appeal to the electorate through a double dissolution may offer not a solution but rather an exacerbation of the situation. Why would the Coalition be in this unusual position? So long as their vote held up, the Greens would emerge with a greater number of senators, simply because the quota in a double dissolution is half that required to elect a senator in a normal half-Senate election.

Even in a scheduled half-Senate election next year, the likely appearance of new players will work to confound the punditry. Bob Katter’s Australian Party will almost certainly pick up a seat in Queensland and possibly also one in New South Wales. There is mounting speculation that Tasmanian independent Andrew Wilkie will abandon his lower house seat and run for the Senate where, given his prominence and the quirks of the Tasmanian electorate, he stands a fair chance of election. And can the resurrected Democratic Labor Party do it again in Victoria?

At present, the Coalition holds thirty-four seats against thirty-one for Labor, nine Greens, one DLP and one independent. In 2013, both the Coalition and Labor will be defending eighteen seats apiece; but the Greens will be defending only three, with their six other senators not facing re-election until 2016 (or at an earlier double dissolution, as the case may be). The Greens, therefore, are unlikely to have their net numbers reduced next year and may in fact gain seats.

The Coalition will be hoping its vote holds up sufficiently to win control of the Senate. In a chamber of seventy-six, this would require thirty-nine seats, which is likely to be beyond its reach. The best-case scenario for the Coalition is taking three of the six seats in each state and one in each territory, giving it a total of thirty-six.

The strongest state by far for the Coalition is Queensland, but this is also the home ground for the Katterites, who will take more votes from the Coalition than from Labor. Labor’s dismal polling in the Sunshine State suggests it may win only one of the six seats, but two seems more likely. Labor, on aggregated poll data, does not look like picking up three seats in any state.

The performance of the Greens will depend to some extent on what Labor decides to do with its preferences, and this could be vital, especially in the final seat in Western Australia, and possibly also in South Australia and Queensland. On current poll figures, the Greens will comfortably hold their seat in Tasmania (and even have an outside chance of picking up a second seat there at the expense of the Coalition), and stand a good chance of picking up the sixth seat in Victoria and just possibly in New South Wales.

Sarah Hanson-Young looks like having a fight on her hands in South Australia, where the popular independent, Nick Xenophon, who was the third in order of election in 2007, will draw many non–major party votes, splitting the result and producing a possible split of three Coalition, two Labor and one independent. But Hanson-Young is by no means out of the running, with a chance, depending on preference flows, of finishing ahead of the Coalition for the sixth seat. Scott Ludlam, in Western Australia, is similarly placed: in danger but not out.

It is worth remembering that in 2010 the Greens made history when they won a seat in each of the states – a first for a minor party. Their vote remains steady around 12 per cent nationally.

But, as I said before, the final complexion of the Senate defies predictability. Where, for example, was the DLP on the political radar before John Madigan took the sixth seat in Victoria in 2010 with just 0.04 per cent of the primary vote? Or, for that matter, Family First’s Steve Fielding in 2004, with 0.08 per cent?

If it finds itself just short of a majority, the Coalition might find allies among the Katterites and the DLP, but this will require some heavy horsetrading, just as it would to woo Nick Xenophon or even a newly translated Andrew Wilkie. As things stand, however tenuously, the Greens may well be decisive in the post-2013 Senate, and it is a not unreasonable question to pose to Abbott: how will he deal with them?

The answer is crucial, but don’t hold your breath waiting for it. •

Norman Abjorensen is a Visiting Fellow at the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Asia and the Pacific, at the Australian National University.

Updated with corrections.