When government MPs talk about tackling Australia’s housing crisis their mantra is “supply, supply, supply.” Michelle Ananda‑Rajah used the phrase when she was launching new homes in her electorate of Higgins. Backbenchers Graham Perrett and Peter Khalil deployed it in support of the government’s Help to Buy scheme in parliament. The slogan was on the prime minister’s lips as he spruiked new housing measures agreed at national cabinet on 10 May.

It seems obvious that building more homes should moderate prices and rents and make it easier for Australians to keep a roof over their heads. This is the logic behind treasurer Jim Chalmers’ budget speech. As he put it, “More homes means more affordable homes.”

But the link is not as straightforward as it appears.

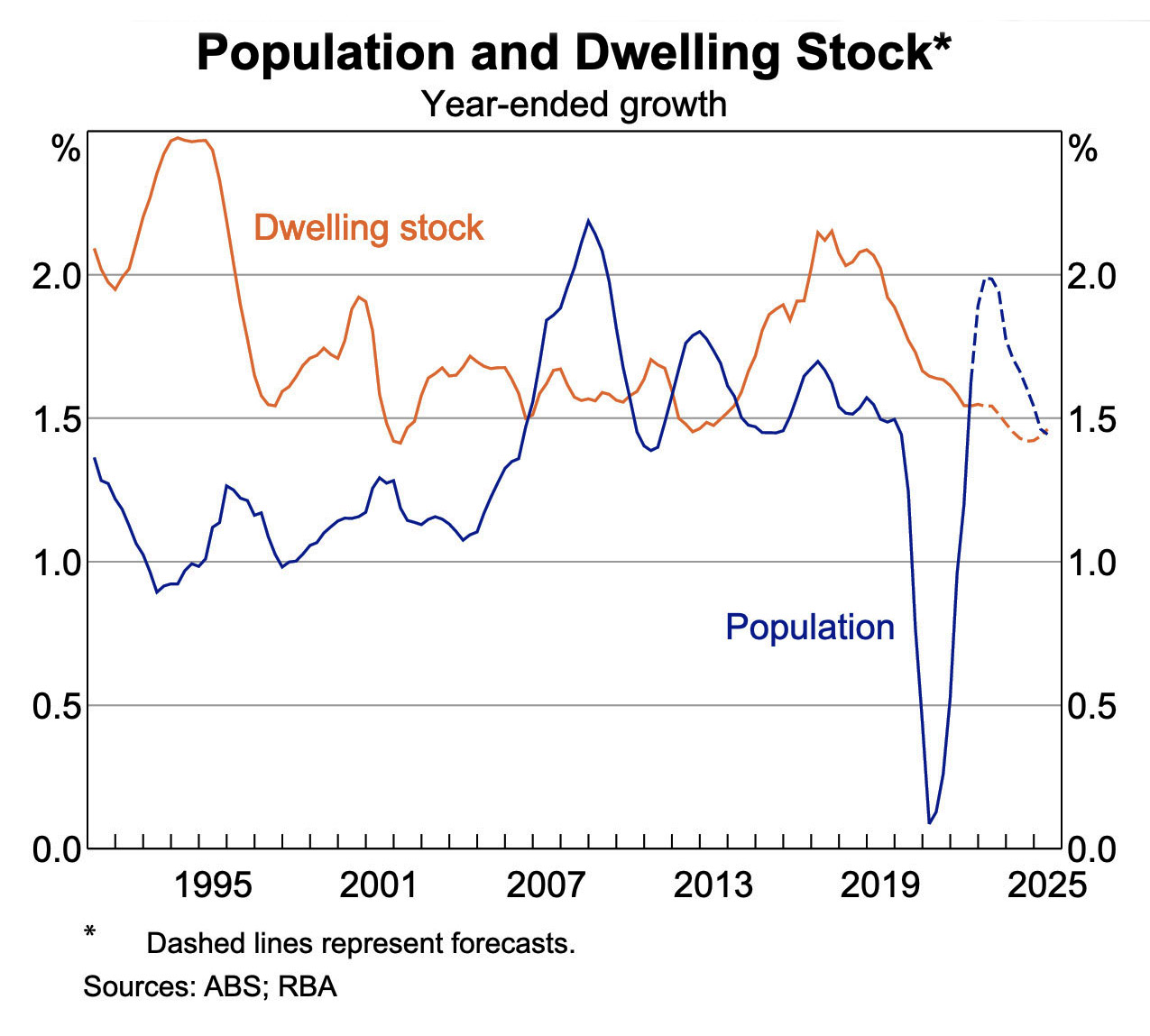

For a start, the growth in Australia’s housing stock has exceeded population increases for much of the past three decades. According to the “supply, supply, supply” theory, this flow of new dwellings should have held back prices. Why then, has the cost of housing been escalating so rapidly? In 2000, the median house price in Melbourne was less than $200,000. Now it’s more than $1 million.

Source: “Monetary Policy, Demand and Supply,” Reserve Bank, 5 April 2023. Dashed lines represent forecasts.

Part of the explanation lies in the fact that households are getting smaller. For decades, families have been having progressively fewer children; and, as the population ages, more people are living alone or in couple-only households.

This trend accelerated during Covid. As Reserve Bank assistant governor Sarah Hunter pointed out in a recent speech, many young people moved out of group houses to live alone or with their partners during the pandemic. When household size falls, the number of dwellings must increase faster than population growth to accommodate everyone.

Then there are cyclical factors. “It takes a long time for housing supply to respond fully to shifts in population growth,” former Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe pointed out in 2023. “In the previous episode of strong population growth, it took around five years.”

We are hitting once such lag right now. With immigration surging after borders reopened after the pandemic, population is growing strongly. International students and other temporary migrants returning to Australia initially seek to rent in the private market. In the short term, this can push down vacancy rates and push up prices, at least in areas close to universities.

Widely quoted research for the Property Council found that international students make up only 4 per cent of all renters overall, but this figure was based on the 2021 census when, thanks to Covid, international student numbers were unusually low. The proportion today is probably closer to 7 per cent. The research calculated that about 47,000 international students lived in purpose-built student accommodation in 2021, with others concentrated in suburbs close to educational institutions. So the sharp jump in arrivals has put added pressure on the rental market, though these temporary migrants can hardly be blamed for significant rent hikes before borders reopened.

Still, it will take time for construction to respond to population changes — more people and smaller households — especially as the industry has entered a downturn. Data compiled by the Reserve Bank shows housing investment is significantly lower than it was a few years ago. This may partly be a result of the Morrison government’s HomeBuilder scheme during pandemic. At a cost of $2.3 billion, it brought forward a lot of construction activity that would have happened anyway.

The government wants 1.2 million homes built over the next five years. In his budget speech, the treasurer said this ambitious goal was achievable “if we all work together and if we all do our bit.” In the prevailing market such optimism seems unwarranted and suggests a naive take on the hard-nosed business of residential construction.

People build new homes when they can afford to do so; developers construct apartments when they expect to sell at a profit. Current business conditions are not conducive to either private or corporate investment thanks to such factors as higher interest rates, labour shortages and the rising price of building materials. The RBA’s Sarah Hunter calls it a “perfect storm” of constraints.

Restrictive councils and objections from well-heeled NIMBYs often get the blame for the lack of new building, which is what the treasurer is hinting at when he says we wants everyone to pull together and do their bit. Veteran economic commentator Chris Richardson spoke more bluntly on ABC Radio, arguing that progress requires “the feds to kick the states to kick the councils.” True, planning regimes and zoning rules can impede residential development. But they are not the cause of the current downturn, and it would be wishful thinking to expect reform at the level of local government to solve all our housing problems.

Rather than simply repeating the motto, “supply, supply, supply” we need to dig a bit deeper. The question is not just “Are we building enough homes?” but also “What kinds of homes are we building and for whom?”

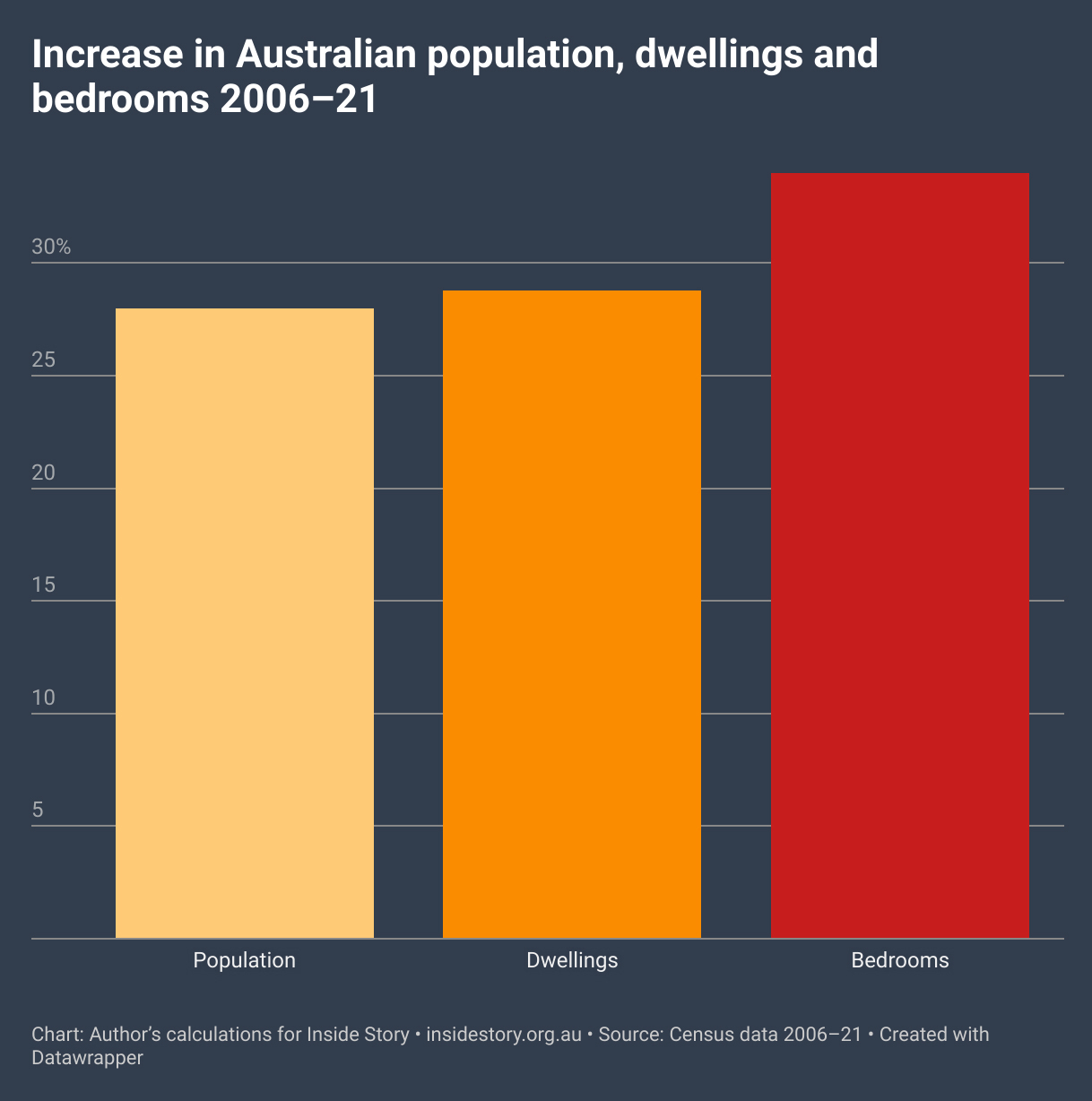

The trends in Australia are clear. Families are having fewer children and more people are living alone or as couples. According to the supply theory, the market should be meeting this demand by delivering homes with fewer bedrooms.

But my analysis of census data between 2006 and 2021 shows the opposite is happening.

In 2006, about 71 per cent of dwellings in Australia were “modest” homes with three or fewer bedrooms. The other 29 per cent, which I call “large,” had four or more bedrooms. Fast forward to 2021, and the share of modest homes has fallen significantly to 65 per cent and the share of large homes has grown strongly to 35 per cent.

Between 2006 and 2021, the number of dwellings grew at a slightly faster rate than the population — 29 per cent compared to 28 per cent — probably insufficient to offset the trend to smaller households. Yet we built enough bedrooms to comfortably accommodate everyone, with an overall increase of 34 per cent.

Chart excludes dwellings where the number of bedrooms was not stated or not applicable.

As a result, Australia has lots of underused housing. At the 2021 census, more than 4.3 million homes (44 per cent of all dwellings) had two or more spare bedrooms. More than a million of these, remarkably, had three or more bedrooms “in excess of need.” If the intention of housing policy is to put a roof over as many heads as possible, then we’re going about it in a very inefficient manner. The labour and resources we plough into building some of the biggest homes on earth should instead be directed into building more modest homes with fewer bedrooms.

This alerts us to three considerations that complicate the “supply, supply, supply” picture.

First, demand for housing is not driven just by demographic factors like population growth and declining household size. It is also driven by increased wealth. As people get richer they tend to “consume” more housing. This can take the form of holiday houses and other second dwellings, or extensions to existing properties. Rising incomes have also fuelled the tendency for developers to build “dream homes” with at least four bedrooms in greenfield estates on the edge of cities. The Morrison government could have countered this trend by investing in social housing during the pandemic; instead, its $25,000 grants to build or renovate favoured people on middle to high incomes.

Australia’s housing problem is not just a problem of supply but also one of distribution, and the inequalities will only get worse as the gap between rich and poor grows.

Second, the shift away from modest homes reflects tax settings that encourage Australians to over-invest in property. The primary residence is completely exempt from both capital gains tax and land tax and is not included in the assets test for assessing the age pension. Thanks to a generous capital gains tax discount, windfall gains on additional dwellings like holiday houses are taxed lightly compared to wages and other income. And since Australia abolished all state and federal inheritance taxes more than four decades ago, residential property has become the primary vehicle for transferring family wealth between generations.

With political will, we could adjust our tax settings to discourage over-investment in property. This would encourage the construction of more modest homes and dampen the speculation that fuels real estate prices. It could also have wider economic benefits as capital flowed into more productive sectors.

The third consideration is the role of government. In a market economy, investment is attracted by opportunities to maximise profits. As a result, the wants and needs of wealthier Australians overwhelmingly shape residential construction, leading to an over-production of large dwellings relative to modest ones. Government could moderate the mismatch between household size and dwelling type by adjusting market incentives.

Most importantly, governments could boost the supply of modest dwellings directly by funding the construction of more social housing — that is, homes low-income earners can afford because their rents are pegged to no more than 30 per cent of their incomes.

In 2001, more than 5 per cent of Australia households lived in social housing. By 2021, the share had fallen below 4 per cent. If state and federal governments had invested enough to keep the ratio stable, then we would have at least 120,000 more households living in social housing than we have today.

As Michael Pascoe has pointed out, in 1971, governments built almost 19,000 dwellings. If we’d kept building at that rate, we might not have a social housing waiting list today — it would certainly be a lot shorter. A substantial, steady and predictable flow of public investment in housing would also help to moderate the ups and downs that plague private residential construction.

After a decade of neglect, recent state and federal investments in housing, including those announced in the budget, are welcome. But they fall well short of what is needed. Labor recognises that Canberra must play a bigger play in the housing system. But if the Albanese government is serious about tackling Australia’s housing crisis then it’s going to have to do much more than kick the states to kick the councils and chant “supply, supply, supply.” •

The text of this article was amended on 23 May to correct errors relating to international students as a share of all renters and the proportion of international students living in purpose built student accommodation. Thank you to the Guardian’s Nick Evershed for alerting us to the mistake.