Labor officials hyped their last federal election campaign as “the biggest grassroots effort in Australian history,” with Bill Shorten claiming in caucus that the party’s 162,000 volunteers had knocked on the doors of more than half a million uncommitted voters and made more than 1.6 million phone calls.

This model of data-driven grassroots mobilisation has played a growing role in state and federal elections over the past decade, and is recognised as a formidable weapon in Labor’s armoury. But the overlap of the NSW and federal election campaigns over the next few months will test whether the party can sustain the effort — and re-energise its teams of organisers and volunteers — at a critical time.

NSW voters will elect a new government on 23 March. A fortnight later, prime minister Scott Morrison is expected to announce an 18 May federal election. Labor’s officials, field directors and volunteers will need to turn around, having won or lost the state election, and do it all again for the federal campaign. Can they pull it off? How many volunteers can they recruit, and how many conversations can they conduct?

The idea behind Labor’s grassroots mobilisation model is simple. By gathering and analysing voter data, Labor seeks to identify and locate “persuadable” voters and then send trained volunteers to meet them on their doorsteps or speak with them by phone. This hybrid — technology-intensive and labour-intensive; highly mediated but personalised and conversational — is derived from the successful micro-targeting campaigns of Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012.

According to proponents of the model, the days of “air war” campaigns built around saturation advertising on network TV are gone. Volunteers are back, in a data-empowered “ground war.” Evidence from the United States suggests that a one-on-one conversation with an uncommitted voter, especially in person, can be a highly effective method of making converts to the cause. But because this campaign model needs a vast labour force, it is relatively inefficient: it requires a long lead-up time to recruit and train sufficient numbers of volunteers; and persuasion, inevitably, is a hit-and-miss task.

Why the attraction then? As one Labor campaigner says, “It’s something we can do that the Tories can’t.” The party has traditions of collective mobilisation and community organising, and has accumulated the necessary data, organisational know-how and confidence to mount significant grassroots persuasion efforts. And it can draw on the ever-replenishing ranks of Young Labor members for the all-important field director role.

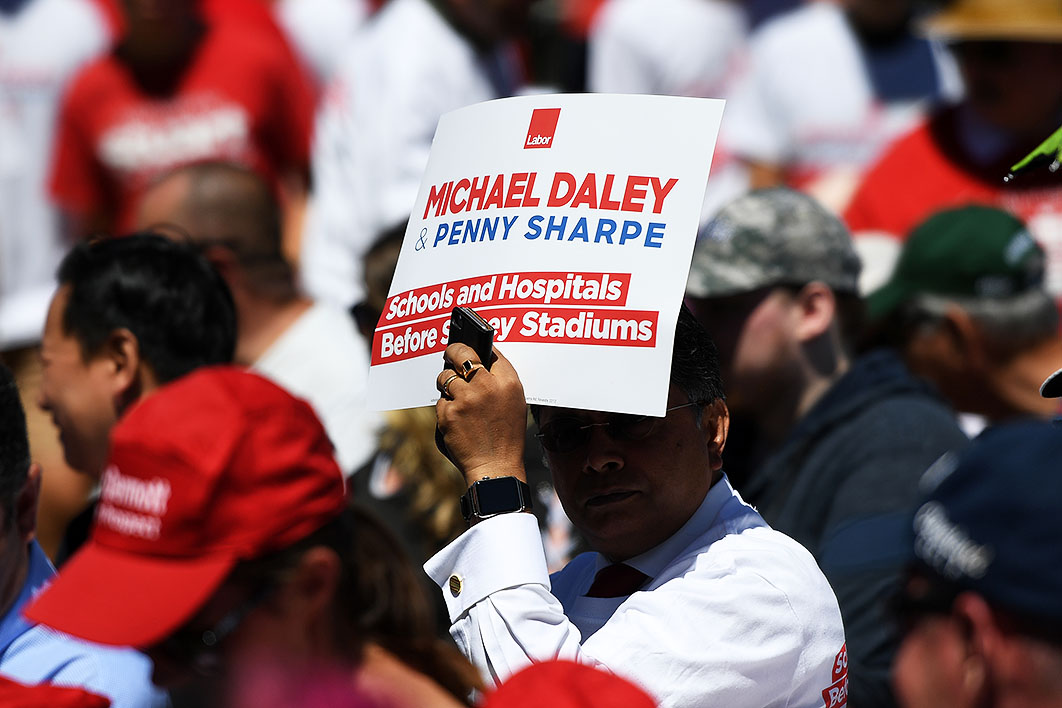

All of this was in evidence recently in a park in the western Sydney suburb of Kings Langley, where Labor’s NSW branch was officially launching its ground war and showcasing new state leader Michael Daley. Present were the campaign bus, balloons, printed placards, candidate posters, t-shirts, caps and merchandise, all in the party’s red-and-white colours. Shadow ministers and local members mingled with unionists and party members — and two dozen or so Young Labor activists, the heart of Labor’s fieldwork campaign. It was a rare outing in the sunshine for these field directors, who are more likely to be hovering over a Campaign Central screen in a darkened call centre.

Kings Langley is in the Liberal seat of Seven Hills, which has been held by former police officer and local councillor Mark Taylor since 2015. Taylor’s 8.7 per cent margin makes it “safe Liberal,” according to election analyst Antony Green. But the presence of Daley, the campaign bus, and the Young Labor contingent underlines the fact that Labor sees Seven Hills as a winnable seat deserving of grassroots campaigning.

Introducing Daley to the crowd, Labor’s candidate for the seat, local solicitor Durga Owen, put it this way: there are just six weeks left until the state election on 23 March, and that means “forty more days of phone banking, five more weekends of doorknocking, forty more early mornings at the train stations getting the message out.” Deputy leader Penny Sharpe had the same message for the volunteers who had “literally embedded themselves in their local communities” for the duration of the campaign.

Forty days sounds like a decent final surge, but in fact Labor’s fieldwork program rolls out over a twelve-month cycle. Although the party doesn’t routinely provide information about the mechanics of its fieldwork, we know quite a bit about it thanks to a report last year on Victorian Labor’s troubled fieldwork effort during the 2014 state election. Ombudsman Deborah Glass released party documents and interview transcripts from her investigation into Labor’s innovative but, as it turned out, deeply improper use of parliamentary staff allowances to help fund its fieldwork.

According to Glass, the state Labor Party began its fieldwork campaign for the November 2014 Victorian election a full year in advance, when it advertised for, appointed and trained some two dozen field directors. From early March 2014 — thirty-eight weeks from election day — these field directors “embedded” themselves in target seats, assembling voter lists, recruiting volunteers and building the local campaign infrastructure. It was a four-phase process, the first three building the local field organisation through “list and organisation building” (twelve weeks), “community engagement and team building” (nine weeks) and “team training” (six weeks). Volunteers — typically, Labor supporters with the time and enthusiasm to do the actual voter contact — were recruited and trained in the use of Labor’s online network of campaign data, Campaign Central, and in how to conduct conversations with target voters. Only then was the organisation ready for the final phase, “persuasion” (eleven weeks). In Victoria this phase began in mid September 2014, running up to and through the campaign.

Assuming that the NSW branch uses a similar fieldwork model, Durga Owen’s volunteers in Seven Hills are already five weeks into the “persuasion” phase. Five down and six to go. In no sense was the Kings Langley event a “launch” of the volunteer effort. They’ve been hard at it for quite a while.

This coincidence of timing, with a federal election following so closely on the heels of a state election, is unprecedented in the modern era. All the states bar Queensland now operate on fixed four-year terms, but federal elections remain on an errant three-year cycle, with the precise date dependent on prime ministerial calculation. The fieldwork model thrives on certainty of timing, allowing a long build-up of campaign organisation and resources to provide a big volunteer effort leading up to election day.

While the fieldwork veterans of last November’s remarkable state election triumph in Victoria have had the Christmas holidays to recover, NSW Labor is essentially required to conduct two parallel fieldwork operations, with the federal campaign running a few weeks behind the state and only really cranking up once the state campaign has finished.

The logistical and political challenge posed by this clash is well understood among party officials and candidates. It’s a concern that federal grassroots efforts in New South Wales are effectively being masked by the state efforts. At the electorate level, some state candidates have tried running joint doorknocking exercises with their federal counterpart. But electorate boundaries don’t neatly correspond, and a target state seat might not fall within a target federal seat. The messages can also become confused: fieldwork is ultimately about local promotion of local candidates, and not every voter is ready to separate and sequence messages about two different candidates representing two different oppositions under Michael Daley and Bill Shorten.

More fundamental is the question of how much of the organisation assembled for the state campaign will be available, let alone ready and willing, to saddle up for the federal campaign? The risk of burnout is high, among field directors as much as volunteers. Doorknocking and phone banking is, by all reports, tiring, tedious and even demoralising work. The rewards are few; no more than one in five contacts yields a useful conversation, let alone a converted vote.

If it’s true that fieldwork is “something we can do that the Tories can’t,” then it is equally true that the overlap of these elections will selectively disadvantage Labor at the expense of parties relying on mass media (TV ads) and social media to get their message out.

There is also the question of just how large the pool of available volunteer labour is. When does the fieldwork model reach its limits? Labor is already effectively competing for left-leaning volunteers with the union movement, Get Up! and the Greens, all of which mount their own versions of fieldwork campaigning. Independent candidates and members in federal seats are also actively recruiting volunteers, unhindered by having run a state campaign beforehand; among them, Kerryn Phelps, Cathy McGowan and Rob Oakeshott use the NationBuilder web tool to do so. (On the other hand, Labor has a big advantage over independents who have not assembled the voter data that underpin micro-targeted campaigning.)

If the 2016 federal election campaign represented the biggest grassroots efforts in Australian history, it also represented a loss. For Shorten, 2019 is a must-win. The question is whether Labor’s fieldwork effort in New South Wales will have the energy and resources to mount an even bigger grassroots effort than three years ago. •