Let’s put the politics aside. Given the circumstances, yesterday’s national accounts show Australia came out of the first half of 2020 amazingly well. Whatever the Morrison government’s faults in other areas, it handled the crisis capably, and is entitled to congratulations on the outcome.

An unprecedented coronavirus had swept through the country. The federal government had closed the borders. The states had shut down a vast range of economic activity. Yet the economy in that half-year shrank by just 7.3 per cent.

And at 30 June, only 104 people had died — four deaths per million people, one of the lowest rates of any developed country. Compared with where we are now, compared with where others were then, Australia could be very relieved.

Sure, we were in the worst recession for almost a century, as the Australian Bureau of Statistics has confirmed. But we’d known for months that was going to happen. And, misled by very inaccurate modelling by epidemiologists of the likely Covid-19 toll, we expected the economic slump to be much worse.

It could still be worse: the slump might last longer than we expected. The policies adopted so far are appropriate but unsustainable. Governments and households could be facing sustained hard times, forcing difficult choices on us. It would help if we could recover the spirit of national unity that saw instant agreement on the JobKeeper and enhanced JobSeeker payments, which are the real heroes of yesterday’s data.

In the midst of the worst recession since the 1930s, with 20 per cent of workers unemployed or severely underemployed, the ABS records that:

• Household income shot up 5.5 per cent, per capita, in real terms, in the year to June 2020. That’s amazingly high — it hasn’t risen like that since Kevin Rudd and Wayne Swan were driving around throwing money on everyone’s front lawns in 2008–09. Scott Morrison and Josh Frydenberg did the same this time: government payments to households shot up by half, giving us an extra $16.5 billion in the June quarter.

• Corporate profits also soared by $16.5 billion, as the Morrison government naively directed worker subsidies through employers. As Labor’s Andrew Leigh has succinctly testified, many firms have used the handouts to boost profits and executive bonuses.

• Small and medium business didn’t miss out: its collective income shot up by $8 billion or 21 per cent. Amid the genuine tough-luck stories, many small business owners accustomed to hard times must have looked at their handouts and wondered what to do with them.

I’ll bet that’s not what you expected to hear. Australians in the June quarter might have been without work, but apart from those the government deliberately excluded from its handouts — casual employees, foreign students, temporary workers and universities — they were not short of money.

The federal government was sloshing money around. In the June quarter alone, year on year, its bill for subsidies jumped from $3 billion a year earlier to $51 billion. Its welfare handouts shot up from $32 billion to $48.5 billion. And that all happened while its tax revenue for the quarter plunged by $12.5 billion.

So with all this money, how did we end up in recession? Well, mostly, we didn’t spend it. We saved it instead. This is what the ABS reports we saved in the June quarter, compared with a year earlier:

Households: $59.5 billion ($7.1 billion)

Business: $50.0 billion ($11.1 billion)

Government: –$82.6 billion ($10.8 billion)

Why didn’t we spend the money? In some areas we did: the ABS says Australia was unique in reporting rising spending on durables such as furniture and household goods. But we couldn’t spend it on some things, because governments had shut down hotels, restaurants, arts venues and night spots. They also stopped us travelling; even with credit cards and internet shopping options, we spend far less sitting at home than we do when we’re away.

Consumer spending, after seasonal adjustment, has fallen 13.2 per cent this year. We don’t know how much was due to the lockdowns and border closures, how much to Australians’ fear of catching the virus, how much to our fear of what the future holds, and how much to simple inertia. But the answers to that question will have a lot to do with how we cope in future.

The ABS cites one telling example: household spending on health services in the June quarter was down 25.6 per cent from the same quarter last year. In part, that was because governments, misled by the modelling and the rapid spread of coronavirus in some places, shut down elective surgery because they feared the resources would be needed to treat coronavirus patients. (They weren’t.) And the publicity created a climate of fear that made some Australians stay home rather than go to doctors’ rooms or pathology clinics for tests or consultations.

That could cost us in the long run. Tests for diseases such as cervical cancer are reported to have fallen sharply. And most cancers are far more deadly than coronavirus.

We’ll come back to the future. It’s an indication of how long ago the June quarter seems now that some were surprised yesterday to learn that New South Wales, not Victoria, was the state leading Australia down. We’ve already forgotten that the epicentre of our first wave was Sydney, where the Ruby Princess outbreak and a couple of outbreaks in nursing homes dominated Australia’s caseload and its economic impact.

State final demand (total spending) crashed 9.8 per cent in New South Wales between the December and June quarters, compared with an 8.7 per cent fall in Victoria, 7.5 in South Australia, 6.2 in Queensland, 5.6 in Tasmania, 5.1 in WA, and 4.1 in the Northern Territory.

You will note the Australian Capital Territory is missing from that list. Its state final demand suffered a small blip in the June quarter, but that was outweighed by the surging demand in March. Its spending in the first half of 2020 rose 0.3 per cent while it was falling everywhere else. Canberra already had serious economic momentum coming into 2020, and coronavirus has failed to stop it.

The ACT government read the modelling and erected a temporary hospital on Garran Oval opposite Canberra’s main hospital. That was complete in May, and it has yet to see a single patient; it is now just a Covid testing facility. Indeed, according to that wonderful trove of coronavirus facts, covidlive.com.au, no one has been admitted to any hospital in Canberra for coronavirus since April. Only one in every 700 tests in the capital has discovered anyone with coronavirus, and just seven minor cases have been diagnosed since April.

It sums up one problem facing Australia that, despite this, Canberra residents are banned from travelling to Queensland and Western Australia — Queensland even designates the national capital as “a coronavirus hotspot” — and have to undergo fourteen days’ quarantine on arrival in South Australia and Tasmania. Even Scott Morrison’s worst enemies must concede he has a strong case for trying to open the borders.

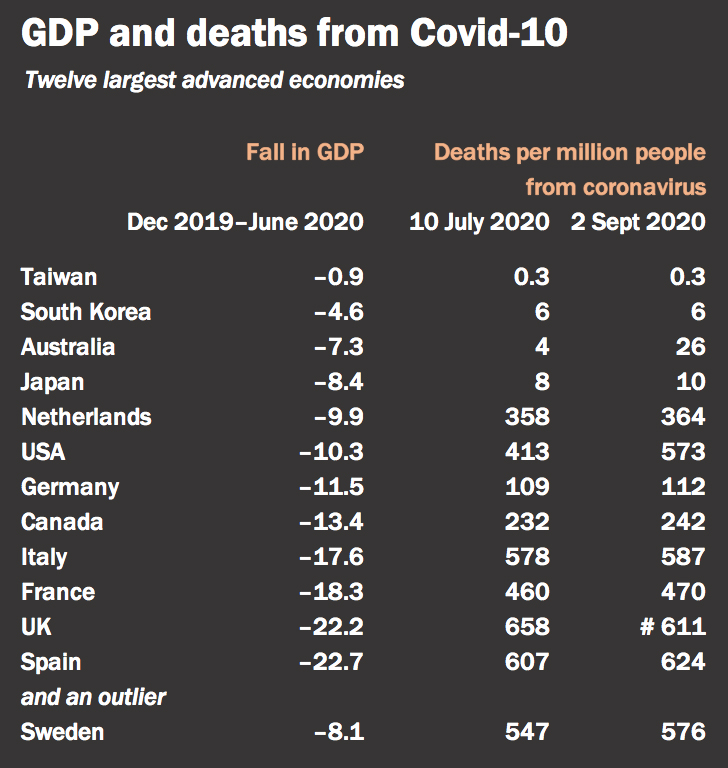

How does Australia’s economy compare with those of other countries? Not as well as the government claims, but pretty well. Of the thirty advanced economies that have so far reported their GDP for the first half of 2020, the 7.3 per cent fall in Australia’s output was the sixth-best outcome, behind Taiwan, South Korea, Finland, Hong Kong, Lithuania and Norway. Of the twelve largest advanced economies, Australia’s had the third smallest fall in output.

Sources: GDP figures from OECD and national statistical agencies; coronavirus figures from Worldometers.

# Britain recently redefined “deaths from coronavirus” to exclude anyone who took more than twenty-eight days to die.

What stands out sharply from the data is the link between the severity of the coronavirus in each country and the severity of its economic slump. The island countries of East Asia and the Pacific are the standouts — partly because an island is easier to lock up than a country in the middle of Europe, but also because, in the first wave, they handled their response well. And Australia is the only one whose second wave has been worse than the first.

In most of Europe, where coronavirus cases and deaths appeared to have settled down, they are now firing up again, especially in Spain and France: yesterday they reported 8581 and 7017 new cases respectively. The resurgence of the virus in western Europe, the United States, Victoria, New Zealand, Indonesia, the Philippines and even South Korea underlines how talk of “eradicating” the disease without a vaccine is farcical. It will be around for a long time, and — lockdowns or not — it will weigh down our economy.

Frydenberg says Treasury forecasts a flattish GDP outcome in the September quarter, which he hopes will be followed by a rebound in December as Victoria’s restrictions ease. He points to job figures that show how, outside Victoria, all states and territories are seeing strong job growth and just over half the jobs lost earlier have come back. Against that, the cost of Melbourne’s stage four restrictions, and the national lockout of Victorians, has severely reduced the economy’s output. A flat result for this quarter would be a lucky escape.

Most areas of consumer spending fell in the June quarter, but the big fall was in two of them. Hotels, cafes and restaurants absorbed a third of the total reduction in household spending, and transport operations (including using our own vehicles) another third. (Spending on entertainment and healthcare were the next biggest casualties.)

Those losses can be made up only by governments removing restrictions: lockdowns and border closures. Even now, governments are still keener to impose new restrictions than to lift old ones. The opinion polls leave no doubt that that is what voters want them to do. It would be a surprise to all if Queensland premier Annastacia Palaszczuk lifted her border restrictions before the state election on 31 October, no matter how ridiculous they are. And WA’s state election is not until March.

International borders remain as closed as ever, making it hard to disagree with Qantas chief Alan Joyce’s forecast that normality will only return in the second half of next year. The new outbreaks of coronavirus — even in New Zealand and South Korea, let alone Victoria — make it unlikely that we’ll see a bubble of Covid-safe countries in the region reopening travel to each other anytime soon.

Australia did well in the first stage of the crisis because the nation united behind a sensible, pragmatic policy agenda combining international border closures with tough lockdowns at state level to bring the virus under control, and a very expansionary fiscal policy at federal level to cushion Australians who lost their jobs. That policy was appropriate and successful — but completely unsustainable.

In the June quarter alone, Australia’s governments borrowed a net $82.6 billion; the federal government borrowed almost three-quarters of that. Ultimately, government debt is our debt: repaying it comes out of our future taxes and entitlements.

Sure, we could go on borrowing to maintain JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments at current levels and expand them to cover all the people left out, to increase subsidies to nursing homes, to bring forward and expand tax cuts, and to do all the other things we would like government to do. But if we want these things, and we don’t want to pay for them, then they will become a charge on our children and grandchildren.

We need to prioritise. We need a national debate on what our priorities should be, knowing that any spending increase or tax cut comes at the cost of others. Back in July, the government set out a timetable for reducing JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments, but it is coming under heavy pressure from Labor and like-minded economists to leave them as they are. There are good arguments for that, as the Guardian’s Greg Jericho and others have spelt out. But the government’s original program was not unreasonable, and I can’t see why maintaining payments at current levels should be a top priority.

Surely the top priority for the federal government now is to fix the mess it has allowed to develop in our dangerous, under-resourced nursing homes. Morrison has tried to pin the blame for the appalling death toll in Victorian nursing homes (which are a federal responsibility) on the state government. That won’t work, as the Victorian figures of deaths and recoveries from the virus (as at 2 September) demonstrate:

In aged care: 433 deaths | 577 recoveries | 43 per cent died

Everywhere else: 158 deaths | 15,575 recoveries | 1 per cent died

It is not simply a matter of providing more funding, although that has to be part of it. Morrison and his government must also ensure that the money is being used directly for patient care, not for the homes’ owners to splash on expensive lifestyles.

This means requirements to ensure that privately owned homes, like state-owned ones, have adequate numbers of staff, especially registered nurses, and provide adequate training — and pay — for non-nursing staff. It would also be a good move to refer the potential misuse of federal nursing home subsidies immediately to the royal commission.

Another priority would be to seize this opportunity to lift unemployment benefits permanently and significantly, and reduce job-search tests to realistic levels. A third would be a joint program to invest with the states in a one-off building boom for social housing, which formed a successful part of the Rudd government’s stimulus when housing construction crashed in 2009.

Others will have other priorities. We need to debate them all, recognising that governments are going to have to make hard choices between them. There are no soft options ahead. •