Thinkers across the ages have taken a generally sunny approach to adversity, convinced that we can be ennobled — or at least educated — by our suffering. Aeschylus mused that “nothing forces us to know what we do not want to know except pain” and Confucius outlined three methods by which we may learn wisdom: “first, by reflection, which is noblest; second, by imitation, which is easiest; and third, by experience, which is bitterest.”

And so, during the bitter harvest of the Covid-19 pandemic, we have gathered the pedagogical fruits of our discontent. We’ve discovered a new-found appreciation of nature — flamboyant skies, the ruffled silk of the ocean in the early morning — we’ve become unnervingly excited about seeing our friends, and we’ve developed empathy for people on the margins. Reliant on seemingly arbitrary decisions by immigration department officials to reconnect with loved ones overseas, we might have a better understanding of the experiences of migrants.

And if we were among the one in five Australians who experienced high or very high levels of psychological distress during the pandemic, or if we have care of someone with a mental illness, we now have some experience of what it’s like to navigate Australia’s broken mental health system. We now know what our system of “care in the community” really feels like.

Australians went into the pandemic with a mental health system that was already shattered. As the recent Victorian royal commission found, funding has not kept up with demand in Victoria, nor in any other Australian state. If you are in need of care today you are unlikely to be able to access treatment close to your home, and you’re likely to be prescribed medication rather than therapy. And if you reach out to a hospital for help, you will probably be told you’re not sick enough to be given one of the few psychiatric beds available. The threshold for accessing mental health services is impossibly high, with many people effectively told that they’re “not suicidal enough.”

If your symptoms are severe, you may be among those whose first encounter is not with a psychologist but with the police, and you may be one of the significant proportion of psychiatric admissions driven to hospital in a paddy wagon. In Victoria, you would have to wait more than eight hours to receive a psychiatric care bed, if there’s room at all. You may have been given compulsory treatment or placed in seclusion or restraint (all of which are routinely used), and you would be released not when you’ve recovered but when your symptoms have abated. Once outside, it’s likely that the women in your life will care for you, unpaid and unrecognised. Care in the community, after all, has almost always meant care by women.

Whether we are experiencing garden-variety Covid flatness (pondering whether R U OK? Day should be called R U Meh? Day), low-level anxiety about government incompetence, or depression at the interminable sameness of our days, or we have reached out for help only to receive a script for pharmaceuticals in place of a professional, we are being given first-hand insights into our mental health system. And this is leading to questions about how our system became so dysfunctional and what can be done.

The Victorian royal commission tells us that “the system’s failures can be linked to its origins”:

In the 19th and 20th centuries, people living with mental illness were separated from the rest of the community and housed in institutions. These institutions began to be dismantled from the 1980s, with a desire to move towards a community-based model of care. But while there has been social change since then, such as a strengthened focus on protecting and promoting human rights and the consumer movement, Victoria’s mental health system has not kept pace.

It’s a common progressivist view of the history of mental healthcare, which starts in the frightful Victorian era, when the mad were locked away in gloomy asylums with narrow windows and long, cold corridors to be shackled, whipped and straitjacketed. Over time, we discovered that people with mental illness were not demons but suffered from medical conditions. By the late twentieth century we had transformed “lunatics” into rights-bearing citizens, patients into consumers, institutions into community care, and straitjackets into pills. The asylum belonged to the monstrous past.

In fact, the history is far more complicated. “It’s not clear whether [the asylum’s] disappearance is a victory for mental health,” writes historian Barbara Taylor in The Last Asylum, a book that weaves the history of deinstitutionalisation into her own experience of being admitted to a British mental asylum. The asylum that Taylor refers to was not the overcrowded, underfunded cemetery for the mad that it had become by the middle of the twentieth century, but the well-regulated refuge for troubled minds that Victorian-era reformers first imagined.

Britain’s self-supporting community of Colney Hatch was a good example. “Its 165-acre site boasted a large farm, orchards, gardens, stables, gasworks, waterworks, laundries, bakeries, and craft workshops manufacturing everything from brushes and beds to boots and clothing of all varieties,” writes Taylor. “Most of the asylum’s food and, by the end of the nineteenth century, all of its clothing were produced on-site by the patients… So idyllic did all this appear that it left more than one mid-nineteenth-century observer convinced that Colney Hatch was a model environment for the sane as well as the insane.”

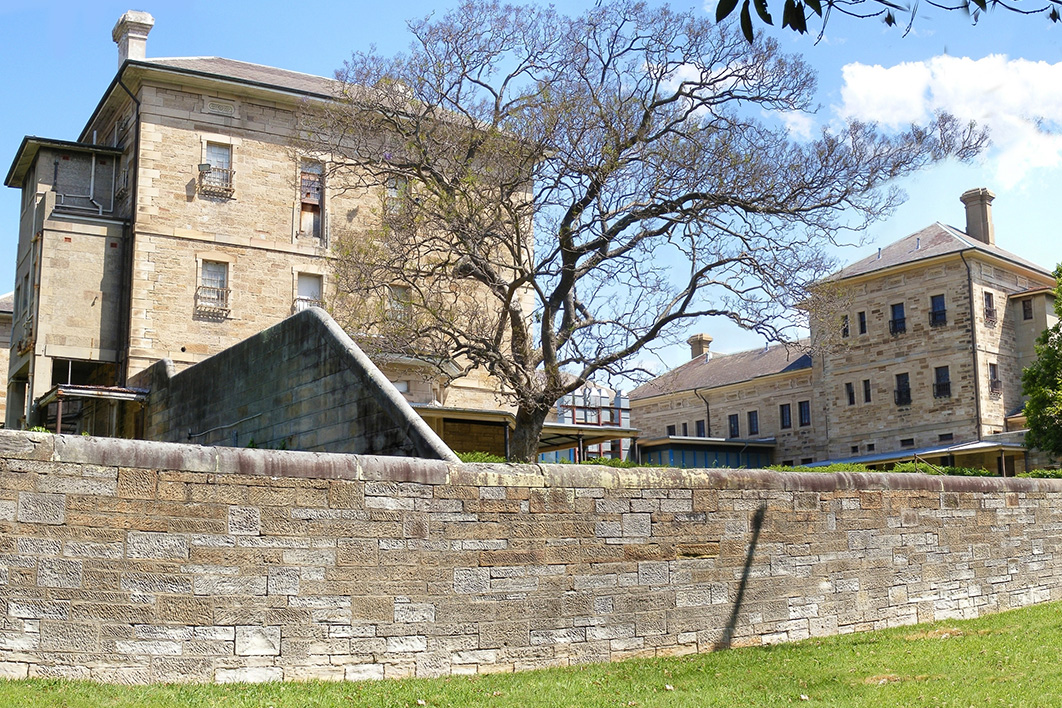

Australia’s first asylum, built in 1811, was designed to sequester “lunatics” deemed “dangerous,” and it wasn’t until a series of inquiries into lunacy law between 1855 and 1868 that a kind of moral enlightenment swept across asylum administration. The focus shifted to moral therapy and medical intervention: the asylum was to be a refuge and a place of reform for troubled minds. The splendid architectural remains of this vision can be seen most clearly today in Callan Park in Sydney, with its pavilion-style layout, views of the Blue Mountains, lofty, airy rooms, summer breezes and landscaped courtyards.

By the twentieth century the language of madness had changed. Eugenicist pessimism usurped Enlightenment optimism and developed treatments to suit its miserable science. With the problem now assumed to be one of genetic defects, the solutions shifted from the social to the physical. Psychiatry shook off the embarrassment of its parentage (the medieval theory of “humours”) and transformed itself into a branch of medicine, with remedies to suit.

Sterilisation, electroconvulsive therapy, prefrontal lobotomies and insulin shock therapy were introduced in the first half of the twentieth century. As psychiatrists imagined more pathologies, the constituency expanded and changed from itinerant men to housewives and servants. As Sydney University historian Stephen Garton has written, this was not a progressive march towards humanitarian care of the mentally ill: “In fact, the older moral therapeutics of the nineteenth century resulted in more humane treatment, less resort to restraint and higher rates of recovery than the psychiatric hospital of the mid twentieth century.”

By the 1960s, when the anti-psychiatry and civil rights movements pushed for the closure of asylums and the right of people with mental illness to live in the community, reform was overdue. Cunningham Dax, the reformer who oversaw deinstitutionalisation in Australia, established a network of medical and rehabilitation services delivered in institutional settings, day hospitals, general practices, sheltered workshops and hospital out-patient departments.

This progressive therapeutic model of community care continued into the 1970s under prime minister Gough Whitlam, who funded modern psychiatric hospitals and innovative forms of treatment, including group therapy and resocialisation programs run by psychologists, occupational therapists and social workers. As psychiatrist John Cade wrote in 1979, these modern institutions were so pleasant that “it is hardly to be wondered at that some people… are resistant to the thought of discharge from such an environment.”

The changes came in 1983 with the Richmond report on institutional care in New South Wales. The report outlined a framework for closing standalone psychiatric hospitals and “mainstreaming” mental health services into an integrated hospital system. Change swept through the system.

Just a decade later, the Burdekin report provided the first official assessment of the catastrophic effects of “community care.” Ever more damning reports, like the one released by the recent Victorian royal commission, have followed. As social historian Virginia Berridge has argued, care in the community has become care by the community.

As we, or family members, or other people we know suffer mental illness because of the pandemic, it seems a good time to try to imagine what a compassionate mental health system would look like. And this means engaging with a more complicated past than suggested by our caricatures of asylums. Is the freedom to be cared for at home by an overburdened family member with no expertise and no financial or medical support a liberty or a loss?

Rather than promoting individualised solutions to mental health problems — mindfulness, R U OK? days, exercise, medication or massages — why not demand that today’s governments spend the same kind of money that Victorian-era governments devoted to asylums or Gough Whitlam put into community care? And why not begin tackling the social pressures that give rise to psychological distress — such as job losses, wage stagnation, housing costs, discrimination, climate change, and fear of violence — rather than pathologising people for their quite rational responses to an increasingly unwell world? •