Afterword added on Saturday 25 March 2017

Donald Trump’s administration faces its first major legislative test this week, with the Republican leadership bringing the American Health Care Act, or AHCA, to the floor of the House of Representatives for a vote. During the election campaign, Trump repeatedly promised to undo Obama’s health reform legacy – which he labelled a “total disaster” – and replace it with “something terrific.” The AHCA purports to do just that.

Yet all the reputable analyses of the AHCA show that it fails to deliver on virtually all of Trump’s commitments. It is politically perilous too: it doesn’t go far enough for right-wing Republicans, it is too hard on older, poorer Americans for more moderate and thoughtful Republicans, and it has been rejected outright by the Democrats. No one in Washington seems to be paying much attention to what voters think; rather, the push is on to get this legislation enacted as quickly as possible with minimum scrutiny.

Given its substantive and political failings and the growing line-up of opponents, it is hard to see how this bill will pass the House, let alone the Senate. The only thing that seems to unite Republicans is the desire to claim that Obamacare has been repealed – which, ironically, is an achievement beyond the scope of this bill. Republicans can’t agree if there should be a replacement for Obama’s scheme, and, if so, what it should look like and when it should commence. More controversially, the current bill is more Ryancare than Trumpcare or even Republicancare, and if the speaker of the House, Paul Ryan, finds himself unable to deliver the votes needed to pass this bill on Thursday, Washington time, he can be certain that the blame will fall squarely on him. Update: The House vote on the bill has been postponed. President Trump has demanded that it be held on Friday, despite the fact that the numbers appear not to be there for the bill to pass.

The AHCA’s rationing of healthcare for poor people to fund tax cuts for the richest is ridiculously unfair. The bill cuts US$880 billion over the next decade from Medicaid, the state-based program that covers people on the lowest incomes, people with disabilities, children with special needs, and a significant amount of nursing-home care, and converts it to a block grant program. Ostensibly, this gives the states more flexibility; in reality, it forces them to ration healthcare services. The cuts will especially hurt the states that took up the Obamacare option of expanding Medicaid to cover more people; it will hit hospitals and healthcare providers as well, and have flow-on effects on Medicare.

The bill also reworks the Obamacare subsidies to help less well-off Americans purchase health insurance through government exchanges or marketplaces. Hit particularly hard will be the 3.4 million older Americans (aged between fifty-five and sixty-four) who have not yet reached Medicare age but have been receiving generous subsidies to enrol in health insurance through the exchanges. Premiums for people aged sixty-four with an annual income of US$25,000 are estimated to rise eightfold, to US$14,600.

At the same time, rich Americans and big business get relief from the “Cadillac tax” and other taxes and levies imposed to fund Obamacare. The net effect is US$542 billion in tax savings, 80 per cent of which go to those whose annual income exceeds US$1 million.

Many people will either drop out of health cover or buy skimpier plans with larger out-of-pocket costs. That will be all they can afford, because the AHCA replaces subsidies with a flat tax credit that ignores income and local costs. On top of that, the AHCA allows insurers to charge older people five times what they charge younger customers, compared to three times under Obamacare.

The much-hated individual mandate, which requires every American to have health insurance or pay a penalty, has been abolished, at a cost to the bottom line of US$210 billion over ten years. Instead, the new bill includes a strange provision requiring insurance companies to levy a 30 per cent penalty on customers who go without insurance for more than sixty-three days. It seems unlikely this “soft mandate” will encourage more young, healthy people to purchase insurance.

Together, these provisions mean that by 2026 some twenty-four million people who currently have health insurance will be without it, either because Medicaid cover was withdrawn or because they can no longer afford to purchase it. Health and human services secretary Tom Price has disagreed strenuously with that estimate, despite the fact that other modelling done for the Trump administration by the Office of Management and Budget predicts that twenty-six million people will lose health insurance.

These provisions would ultimately reduce the cost of health insurance – as promised – but for all the wrong reasons. Many people would be without any insurance, and the remainder would have cheaper policies with less coverage, higher deductibles and higher co-payments. The federal debt would be reduced, but only by US$337 billion by 2026, a drop in the bucket when the gross federal deficit is currently US$20 trillion.

The Ryan bill also punishes women. It completely defunds Planned Parenthood, a major provider of preventive and reproductive services, forbids federal tax credits for any insurance plan that covers elective abortion, and removes the requirement that all plans cover maternity services.

The political ideologies at work, and the potential conflicts, are obvious. This is not the “something terrific” Trump promised his supporters, who will be disproportionately hit by the changes. An Associated Press analysis of data from the Kaiser Family Foundation finds that, on average, counties that supported Trump most strongly will see premium costs for older enrolees rise 50 per cent more than counties who supported Trump the least. The president also promised that no Americans would lose their health insurance under the repeal of Obamacare, a commitment both Ryan and Price have refused to repeat.

Republican House leader Paul Ryan, Senate leader Mitch McConnell and Secretary Price all have a history of proposing savage cuts to Medicaid, Medicare and social security. Ryan is on record as saying he has been “dreaming” of capping Medicaid since he was in college “drinking at a keg.” This is in contrast to Trump, who has promised no cuts to any of these programs – a promise he now seems willing to abandon.

The Republicans’ options are constrained by their decision to use the budget reconciliation process to ram through the legislation and avoid a Senate filibuster (which requires sixty votes to overturn). As a results, key provisions of Obamacare that fall outside the scope of budget reconciliation will remain in place.

For this reason, senior Republicans have begun to talk about a “three-pronged strategy” involving (1) enactment of the AHCA, (2) regulations through the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and (3) more bills to undo core tenets of Obamacare. Yet there is little evidence of any further plans. In particular, Republicans have little chance of mustering the sixty Senate votes needed to pass any further legislation. The biggest threat to Obamacare probably comes from the potential regulatory actions of Secretary Price; these could erode and weaken Obamacare, ensuring it is a continuing disappointment to Americans and eventually justifying Republican claims that it is in a “death spiral.”

Enough Republican members of the House have complained about their leaders’ bill that Ryan has agreed to write up a series of modifications. This marks a significant retreat from his earlier position that the carefully crafted legislation would fail if substantially altered. But he maintains that opportunities for amendment will be limited, declaring bluntly, “Members will face a binary choice to either vote for a bill that can pass or vote for Obamacare status quo.”

Trump, on the other hand, has said, “We’re going to arbitrate, we’re going to all get together. We’re going to get something done.” It’s not at all clear that Trump knows what the AHCA will do and whether he realises the extent to which it ignores his election promises. In interviews, he seems confused about legislative provisions in the bill and uses a repetitive set of talking points and phrases. Given that this is not his bill, his level of engagement is suspect, despite his declaration of 100 per cent support.

Between them, the White House and the Republican leadership must juggle the demands of the conservatives and moderates in both the House and the Senate and listen to the Republican governors, some of whom are concerned about the costs to their state budgets of cuts to Medicaid. A bipartisan effort is out of the question: Democrats will use the same strategy the Republicans adopted when Obamacare was being enacted, and keep their fingerprints off these proposals.

The proposed changes to the Republicans’ bill fall into two categories. To placate right-wing groupings like the Freedom Caucus, limitations on Medicaid will be even tougher, with states allowed to opt for a fixed block grant in lieu of a per-person reimbursement and to impose work requirements on childless adults receiving benefits, and the rollback of the Medicaid expansion permitted under Obamacare would be speedier.

Changes have also been promised to mollify the more moderate Republicans who are worried that the bill would drastically increase costs for low-income, older people and those in rural areas. This provision would come at a yet-to-be-announced cost to the budget.

Will these be enough to garner the necessary votes? In the House, Republicans can only afford to lose twenty-one votes and the House Freedom Caucus is currently withholding more than that number on the basis that its core concerns have not been addressed. In the Senate, where the Republicans will be much more sensitive to the concerns of the states, a different (arguably more difficult) set of demands must be managed. Four GOP governors from Arkansas, Michigan, Nevada and Ohio have announced their opposition to the House bill and their support for the maintenance of the Medicaid expansion provisions, putting the votes of eight senators in doubt.

Republican congressional leaders seem to be betting that rank-and-file party members in Congress will support poorly crafted and poorly understood legislation rather than risk being branded as the Republicans who saved Obamacare. The fact that the reaction so far to the bill has been almost uniformly negative has been ignored, as have the obvious consequences for productivity and the economy.

Encouragingly, though, Americans seem more informed about what is in the AHCA than they were (and continue to be) about Obamacare. The popularity of Obamacare rose almost as soon as repeal became a serious possibility. A Pew Research Center survey in January showed that 52 per cent of Republicans making less than US$30,000 a year believe the federal government has a responsibility to ensure health coverage for all Americans, up from 31 per cent last year.

A recent Huffington Post/YouGov poll shows strong public opposition to the Ryan bill (45 per cent oppose, 24 per cent support) and this is in line with a number of other polls. Just 5 per cent of those surveyed strongly support the bill. A Kaiser Family Foundation poll found that a majority of Americans believe that the AHCA will reduce the number of people with health insurance and increase costs.

Voters who supported Trump are more likely to consider it an improvement on Obamacare, but there’s little enthusiasm. Many Trump supporters have adopted a head-in-the-sand approach, convinced not only that Trump will deliver the reforms he promised and they want, but also that Congressional Budget Office estimates of the number of people who will lose cover are incorrect. Others are dismayed that they might lose the Obamacare benefits they love to hate.

The essential problem confronting Trump and congressional Republicans is that tens of millions of Americans have benefited from Obamacare, and taking away or limiting known benefits is always a difficult political task. Voters have been promised a replacement that costs less and covers more, and it is hard to imagine any Republican plan that can deliver on these promises. It’s unlikely that the blue-collar voters who supported Trump will be won over by the promises from Ryan and Price that they are providing everyone with freedom, choice and access to purchase health insurance if this is unaffordable and of little real value.

Republicans have been shaken by the level of outrage in their districts. They are (rightly) concerned about their ability to satisfy voters’ desires for healthcare improvements and what this will mean for their personal re-election chances in 2018 – a mid-term election that almost always goes against the party in power. Trump’s main arbitration effort to date has been to play on this fear, telling House Republicans that if they vote against the healthcare bill, “many of you will lose your seats in 2018.”

If Trump and Ryan fail at their first major legislative hurdle, then there will be enormous pressures on this “marriage of convenience” (we know that Trump has little tolerance for failure and no ability to accept responsibility when things go wrong), with major implications for the proposed agenda ahead. On the other hand, if the AHCA does pass the House, it faces another set of tough hurdles in the Senate.

Trump and the Republicans are discovering what the Democrats already knew – that healthcare reform is unbelievably complex, and comes with major political consequences. •

Afterword: On Friday 24 March, Washington time, President Trump’s own party delivered him a big defeat on his key campaign promise to repeal and replace Obamacare. The inability of the president and the House leadership to get enough votes to pass the American Health Care Act will have far-reaching ramifications – for Trump’s future agenda, for the shape of America’s healthcare, for relationships between the White House and the Congress, and for Trump’s ego.

It was all too arrogant and predictably wrong-headed. The Republicans had seven years to come up with an alternative to Obamacare, yet they never moved beyond election slogans and made no effort to reach a consensus on how to proceed. House leader Paul Ryan moved too quickly to legislate his own ideological approach and failed to reach out to rank-and-file Republicans. Trump and his administration lacked the intellectual heft to deliver their own proposals and legislative language. Trump himself lacked the commitment and concentration to be involved in the intense negotiations needed to deliver an acceptable compromise, and so he quickly threw in the towel, making the issue about him rather than good (or even acceptable) policy. And no one in the Republican leadership seemed to care at all that voters hated this bill and were calling the offices of their political representatives to make that clear.

Efforts to get more congressional support from conservative Republicans seem simply to drive away the votes of the moderate wing; in the end Ryan was forced to go to Trump with the news that he was more than thirty votes short, and the decision was made to pull the bill from consideration. It’s not clear if there are any plans to bring it back, in what form, and when. Trump’s statements indicate that there will be paybacks against those who opposed the measure (and, de facto, failed to support him) and he will turn instead to the even tougher task of tax reform.

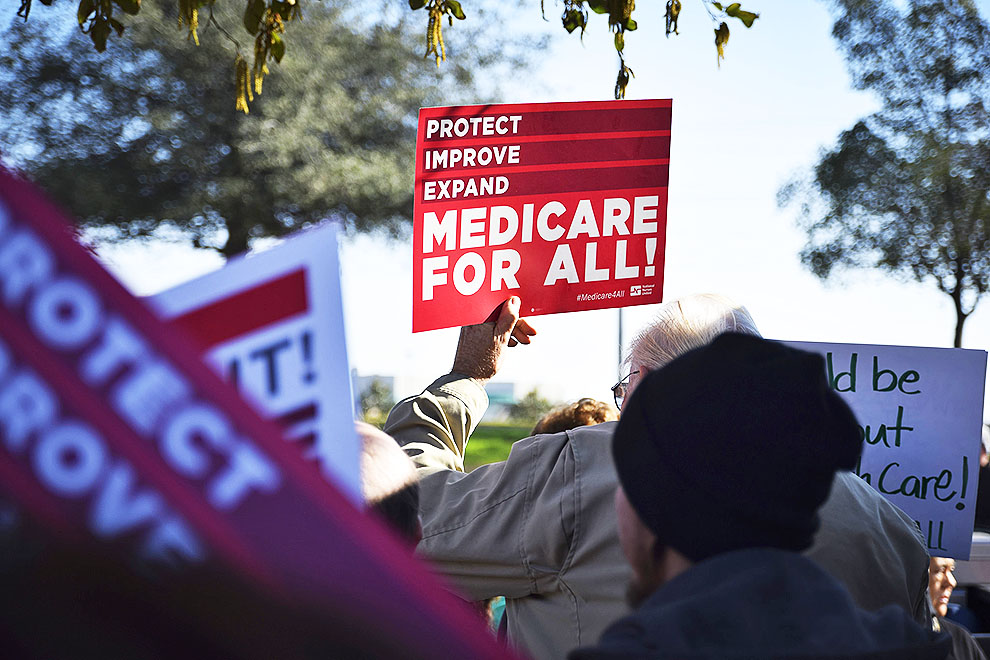

The big concern for those who care about Obamacare is that every effort will be made to ensure it ultimately fails. It is easy for the Trump administration to undermine currently provisions through executive orders, regulations and lack of resources, and Democrats face an impossible task gathering enough House votes to enact needed improvements. A people’s movement in support of the basic Obamacare provisions might be the only way to drive political action.

Meanwhile, only one thing can be certain about Trump’s response to this major set-back: he will stew all weekend and ultimately succumb to tweeting about who is to blame.