Amid the chaos created by Donald Trump’s uninhibited prejudices and powerplay, the view from Australia reveals challenges that demand close understanding and attention. The risks are rising fast.

Essentially, Trump says US voters have chosen to declare economic victory and put a moat around their nation’s consumption. Domestic producers will be protected from foreign competition, whether from China, Europe, Australia or even Norfolk Island.

US defence strategy, which has involved extensive international deployments in a string of bases and alliances, now looks like a protection racket. Friends have become foes, neighbours threatened and enemies like Russia embraced.

While the Morrison government veered sharply toward a tight US alignment, Anthony Albanese has evidently steered back toward the foreign policy basics attributed to John Howard. That is: Australia chooses to have a strong security alliance with the United State while also recognising its economic relationship with China.

In the wake of Trump’s flood of highly provocative policy steps, many of them plainly challenging our notions of a close alliance, even stalwart promoters of the US security relationship are suggesting that Australia should consider a less dependent approach. Given the known uncertainties of the AUKUS agreements, the questions emerging for Australia may be profound. Not least because the outlook for China is also in flux.

President Xi Jinping came to power as a reformer — but not of the kind that characterised the post-Mao economic and social liberalisation. Rather, he appears set on re-establishing a “core leadership” and sustaining the central role of the Communist Party. The second part of that equation is evident in two campaigns that might be termed structural. Xi put a brake on the pursuit of growth through undisciplined and excessive debt and he has prosecuted a long running, top-to-bottom anti-corruption campaign.

The “core leadership” question is harder to pin down because Communist Party politics are rarely exposed to sunlight. Some scholars and commentators have pointed to the lack of firm leadership in Beijing in the period before Xi’s elevation. That is, the tight leadership of the Mao’s successors was lost in the next generation. Some believe leadership during that period was more of a loose feudal structure in which leading figures oversaw their own turf without cohesion or common purpose.

In any case, there’s no doubt that Xi was vested with singular powers and authority — which he has used. And he has been conducting a reform campaign for the CPC and China that is probably at least as cathartic as the one Trump is pursuing. But the two leaders have almost opposite objectives.

China needs to develop a much higher degree of value in its economy to avoid the “middle-income trap” that often bedevils developing nations. Its shrinking and ageing population not only limits any future labour-cost competitiveness but also implies a higher degree of domestic consumption. Its political and economic baggage is considerable.

Xi’s rhetoric and broad strategies have been technocratic in the sense that technology and innovation are priorities. His key phrase — “high-quality development” — captures the idea of higher productivity and higher average incomes as well as improved social outcomes and services. Lately, he has very publicly recognised the key role of China’s private entrepreneurs, having sharply rebuked a number of them in his early years. But he undoubtedly favours state enterprises and those private organisations who very clearly recognise their status obligations within the Chinese system.

China’s and the US position in global trade are even more sharply at odds now, even though US policy under Biden was already aimed largely at limiting Chinese technological and economic growth. As a result of the over-investment of past years, China’s industry has massive capacity in many sectors. And as its growth has slowed, excess capacity has flowed over into exports that have driven down prices in many global markets.

High quality growth — as Xi appears to define it — is also about domestic self-sufficiency, a factor that has become more important as the US has tightened controls on technology and research interactions and trade. China has a wide range of large-scale research and innovation programs, some evident in recent developments in AI and semiconductors and others in ambitious research for biotechnology and health sciences. Xi has also fostered a strong focus on factory automation and advanced technologies in transport and logistics, all designed to enable more sophisticated, competitive product development.

While much of the public focus on tensions between the US and China is on Taiwan and the South China Sea, one clear source of risk for both is fiscal. The US government’s debt and rising deficits are already at levels investment markets baulk at. So far — despite the DOGE rhetoric — Trump’s strategies appear to be increasing deficits and promoting inflation that will inevitably increase the cost of debt repayments. The US government’s interest payments already exceed its defence budget.

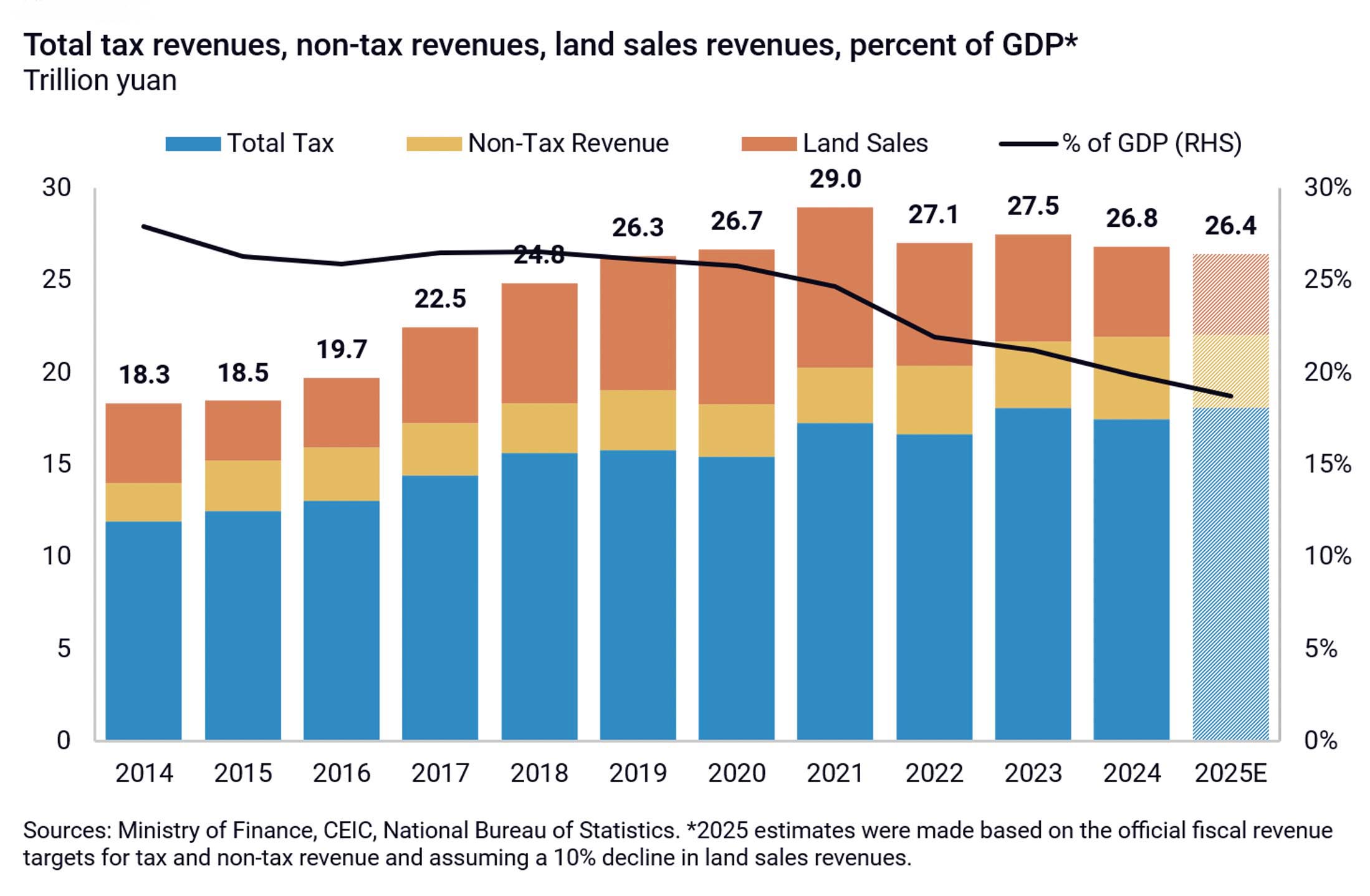

China’s “two sessions” leadership meetings earlier this year were largely rehearsals of established policy themes. But one striking fact emerged. China’s fiscal revenue is not growing. Even though the official measures claimed 5 per cent GDP growth last year, revenues barely grew; and while this year’s GDP growth is again forecast at 5 per cent government revenue is expected to grow only 0.1 per cent.

China’s fiscal revenue 2014–25. Source: Rhodium Group

The reality is that China’s investment- and debt-based economy hit a wall and only a big boost non-tax revenues compensated for the fall in taxes and land sales revenue. Anecdotal accounts suggest that at least some of that non-tax revenue was obtained by dubious means. With the accrued debt of local governments weighing heavily, Beijing can’t keep kicking the fiscal can down the road, especially if tighter international trade terms put more pressure on exporters reliant in some way on government support. China probably faces significant industry rationalisation, which the attendant risk of social instability — something for which Xi has exhibited little tolerance.

Beijing has been moving toward a market-based system for electricity, a reform that offers considerable benefit. But it implies a substantial reduction in the size of the industry — which is huge — because the average load factor is only 50 per cent of nominal generating capacity. Steel is in a similar situation, challenged already by the curtailing of excessive construction investment, and its diversion to export markets is likely impractical and in any case a target of trade sanctions. Even the rising EV sector is facing factory closures, with the regulator of state enterprises announcing in late March that “consolidation” was coming. Where once China had around one hundred EV manufacturers it now has about forty. But many of the more aggressive developers are private companies, so it will be interesting to see how the regulators manage the more “competitive” outcome they have targeted. One way and another, China is in for some big challenges in its fiscal capacity and substantial parts of its employment base.

In a sense, both Trump and Xi have the same political challenge: what Xi has referred to as “common prosperity.” Xi has the job of sustaining the status of the Communist Party, presumably by attacking the corruption among elites that threatened the party’s credibility and by delivering social stability and wider economic equity. Trump promises a return to postwar middle-class comfort and values through economic protectionism.

Both countries need to increase taxes; both have been reducing taxes. Both appear to have little runway left. Decisions will need to be made.

As Xi and Trump work through their very different agendas, one choice stands out. Where Xi promotes technocrats in leadership and pursues technocratic solutions, Trump’s prejudices have already seriously disrupted or simply wrecked a range of hugely influential US research agencies and programs and curtailed research funding at a range of universities. Trump clearly prefers to have inexperienced loyalists in charge and they have made clear their intention to act on his — often destructive — instincts. And while he has cowed or won over America’s digital commerce leaders, their companies are heavily reliant on global open markets. In fact, all of the so-called “magnificent seven” obtain more than half of their revenue outside the US — and in Nvidia’s case it’s closer to 90 per cent.

Washington pyrotechnics have naturally preoccupied people around the world. But it would be wise, certainly in Australia, to keep an eye to our north. China’s leadership faces key decisions that will inevitably affect Australia’s outlook in material and other ways. Elsewhere in Asia, Vietnam’s new leadership has embarked on a massive restructuring of its bureaucratic architecture — a radical development that will go to the heart of its power and policy arrangements. And to our immediate north, Indonesian president Prabowo Subianto appears to be testing the country’s hard-won fiscal credibility with a seemingly illogical budget strategy.

After decades of comfortable, prosperous security Australia’s outlook is clouded by issues that have few easy solutions. It is bad time to make policy decisions that rest on conventional assumptions. •