BECAUSE I live in a safe seat, I’ve only received one letter from each major party this election and each party’s letter begins with the generic “Dear voter…” But it’s a very different story for voters in hotly contested marginal seats. In electorates like Gilmore, Robertson and McEwen – which are among the most marginal in the country – households have been receiving lots of direct mail, and the parties make an effort to personalise it. “Dear Ms Smith” will begin a letter that might differ in its content from the letter sent to Ms Smith’s next-door neighbour.

The internet, Twitter and social networking have attracted a great deal of attention during this election. But I would argue that direct mail – an adaptation of a nineteenth-century election tool, pamphleteering – is much more important. The parties are sending out reams of leaflets, postcards and letters to voters, and they do this because Australian elections turn on the results in marginal seats and on the voting decisions of swinging voters (or the “softly committed”) who live in those seats.

Direct mail can do important things that TV ads – another way of reaching swinging voters – can’t. While TV ads have great reach and impact, their messages must be fairly general because they will be seen by hundreds of thousands of people across different geographical areas. Many of these people will not be in the parties’ target audience: they will live in safe seats or already be committed to one of the parties, and some will be under the voting age.

Direct mail can be sent where it is needed most, and it can carry a highly focused message aimed at specific areas or even households or individuals. Localising the national campaign and sending out targeted messages are seen as vital, especially because of what the parties’ research has found about swinging voters. These voters are believed to be largely apolitical, interested in neither ideology nor abstract political arguments. But they might prick up their ears and pay attention if the issue at hand is a “hot-button” one – like asylum seekers or immigration.

Swinging voters are also known to be less concerned about big-picture themes and more interested in their own circumstances and those of their family and community. They are interested in “hip-pocket nerve” issues such as interest rates, mortgages, grocery and petrol prices, and government benefits such as family assistance or the pension. While they tend to be sceptical about politicians in general and about whether politicians can fix big problems like healthcare, transport or crime, they are more willing to listen if politicians talk about specifics - if they promise to fix a local hospital, school or road, for example.

Direct mail is often called the “hidden campaign.” Because it’s conducted away from the scrutiny of the mainstream media, it can be hard to know what the parties are telling people through their letterboxes across different electorates. But during this election campaign, Inside Story asked voters in the fifteen most marginal seats (all held by less than 1 per cent) to send in any political mail they received. The first batch, covering the opening three weeks of the campaign, makes for fascinating reading. Before I get to the content of that mail, though, I should say something about how direct mail works.

High costs and weak rules

For the major parties, direct mail is usually the biggest campaign expense after television advertising. It’s been reported that the parties have less money, overall, to spend on this campaign because political donations slowed as a result of the global financial crisis (we’ll have to wait until February 2012 to see whether this is true). But even if their private coffers are smaller than usual, the major parties still have the certainty of the millions in public funding they will receive after the election. In 2007, Labor received $22 million and the Coalition received $21 million; the next-largest beneficiary, at $4 million, was the Greens.

These funds certainly help pay for all the TV ads and direct mail. But the parties already have a major advantage for their direct-mail campaigns – the fact that all members of parliament receive a printing entitlement. This year it is $75,000 for each member of the House of Representatives.

The entitlement is based on the sound principle that MPs should communicate actively with their constituents and keep them informed. In the United States, members of Congress receive similar funding to send mail to their constituents. But House of Representatives rules prohibit mass mailings in the period starting ninety days before an election and, by law, the allowance cannot be used for “mail matter which specifically solicits political support for the sender or any other person or any political party…”

In Australia, by contrast, MPs can use their mailing allowance during election campaigns. When the Australian National Audit Office investigated in 2009, it found a high proportion did indeed use their allowance to bombard their constituents with blatantly partisan material.

As with political advertising, the costs of direct mail have been escalating as part of an arms race in campaign spending. In 1999–2000, the average amount spent by Australian MPs using their printing entitlement was $37,287. Eight years later, in 2007–08, MPs who retained their seats at the 2007 election had spent an average of $142,516.

When the Rudd government came to office it reduced the printing entitlement for MPs from the Howard-era high of $150,000 per year to $100,000. Following the Audit Office’s damning report, the government reduced it again to $75,000 and decreed that the entitlement could not be used to print how-to-vote cards (which had been allowed in 2004 and 2007). These were undoubtedly improvements, but they stopped short of following the US example and prohibiting the use of taxpayer-funded mail either during an election or for partisan purposes.

But the most interesting thing about direct mail is how the parties target their messages house-by-house and street-by-street. In the 1980s, both major parties established databases to store information on voters (Labor’s is called Electrac and the Coalition’s version is called Feedback!). After three decades, the information accumulated on those databases is extensive – especially in marginal seats where staffers are under orders to keep it up-to-date.

The rules governing these databases leave a lot to be desired. Political parties are exempt from the Privacy Act so they can use these databases to store information about voters without their consent; they are also exempt from Freedom of Information requests, and so cannot be forced to reveal the contents of an individual’s entry.

The parties use all of the information they have on voters – from the electoral roll, phone polls, door-knocking, voter contact with the MP’s office, focus groups, local media and many other sources – to help them hone the messages they use in direct mail. Individual items can then be targeted to a voter’s area of interest or bulk mail-outs can be targeted by age group, gender or occupation.

Direct mail 2010

Now, to the content. What does direct mail sent to marginal seats in 2010 tell us about the parties’ messages?

The first thing that’s evident in the material from the most marginal fifteen seats is that it uses a lot of the same tricks that we see in political advertising on television. Find an unflattering photo of your opponent and print it in black and white, use bold red type (red, after all, is the colour of danger), point out “the facts” about an opponent, always emphasise the “family” and use as many emotive images as possible – especially of children and of pregnant women waiting to get hospital care. One anti-Liberal pamphlet (below) even shows a sad-looking family with empty dinner plates (because of Abbott’s WorkChoices they have no job, and thus no food).

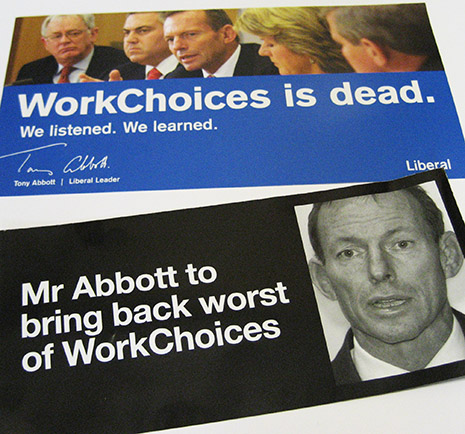

Above: Labor’s not-so-subtle anti-WorkChoices message.

There is a mix of positive and negative messages. Both major parties (we only received one Greens leaflet among all the electorates) try to reinforce negative perceptions about their opponent but Labor also tries to list its achievements in government while the opposition argues the case for a change and promises to do better. The parties aim both to scare and to soothe.

These messages aren’t subtle because they’re aimed at grabbing the attention of uncommitted voters. The emphasis on local issues and local candidates reflects the key characteristic of direct mail. The candidate is “one of us,” a “local” who “understands our community.” There are lots of photos of candidates talking to local people and visiting local sites. National issues are brought down to a local level. A Labor postcard says, “Cutting broadband will hurt our region…” and a Labor letter sent to a family in Corangamite says that Labor has funded a “new $7.5 million superclinic in Belmont” and a “new Southern Geelong Hospital.”

But while a lot of the material is designed to appear local, it’s clear that there is a high degree of coordination from campaign headquarters. This is especially evident in the Liberal material. The party sent out two standard letters to all of the electorates where we collected mail. In each case the letters were the same in all electorates – only the candidate’s name, photo and signature were altered.

In the first letter, the Liberals try to do what challengers must always do – convince voters that things are bad under the current government. We are at a “crossroads,” says the letter, “with so much uncertainty around the world…” We have “an economy still not out of the woods” and have been hit by “increased cost of living pressures… massive debt, budget deficits, waste and mismanagement.” The second letter comes with a copy of the Liberals’ “Action Contract” – a pamphlet with a text-heavy twelve-point plan that it’s hard to imagine many people would read right through.

Individual Liberal candidates also use a standard postcard adapted and personalised for each. All of the candidates are “fighting to get things done” (unless they are an incumbent, in which case, they are fighting to “get more things done”). All are quoted as saying they are “passionate” about “our community.” All of the postcards list five things the candidate is fighting for. In almost all of them, one of these five points is to get “more CCTV cameras in known trouble spots” in the local area. The other promises are, again, national issues localised down to specifics – to make improvements to the “Richmond Road, the Great Western Highway” (Macquarie) or get “public radiotherapy treatment at Gosford” (Robertson) or build a new “Medowie High School” (Paterson) or create “an extension of the train line from Bomaderry” (Gilmore).

Above: “Fighting to get (more) things done”: a single Liberal message tailored slightly to local conditions.

In some electorates, the Liberals especially emphasise asylum seekers. In Robertson, New South Wales, one Liberal postcard has, on the front, a picture of boats being intercepted and, on the back, a promise to do several things including “stamp[ing] out people smuggling” by “turning back the boats where circumstances allow” and to “presum[e] asylum seekers are not refugees if it is believed they have disposed of their identity documents.” (Their emphasis.) In Western Australia, Senator Judith Adams tells voters: “To stop the [mining] tax and stop the boats we need to change the government.” Another pamphlet from Adams (produced, it says, using her printing entitlements) says: “Labor has FAILED on border protection” and again shows a photo of boats being intercepted.

Labor’s mail over the first three weeks of the campaign was more varied. There was no single letter of the kind the Liberals sent out, but there was a large glossy pamphlet with a standard format to promote Labor candidates. It includes an endorsement of the candidate by the PM and three points about him or her that usually emphasise they are “a local,” give some biographical information and refer to results they have achieved in “our community.” In Solomon (Northern Territory), for example, the Labor candidate is said to have achieved “new health services for the Territory” and (echoing the Liberals’ emphasis) “new CCTV cameras.”

Labor has also been sending out postcards that feature a headline in the Sydney Sun Herald in June, “‘Don’t hurtle towards a big Australia’ says PM,” and a quote from Gillard: “We need to stop and take a breath… develop policies for a sustainable Australia.”

Clearly, Australians have fears about crime, safety, congestion, immigration and “sustainable” populations which both parties are drawing on (and reinforcing) in their mail. Sometimes those fears advantage one party over the other, but even the disadvantaged party will tend to believe that there is no point trying to change perceptions in a fifteen-second TV ad or a one-page letter and will play to existing perceptions in order to sound persuasive.

In terms of negative mail, Labor has placed much emphasis on arguing that the Liberals would bring back WorkChoices. (And the Labor material is backed up in some electorates by mail being sent out by unions.) The Liberals have used mail to try to counter this claim. According to one Liberal postcard, “WorkChoices is dead. We listened. We learned.” Another says: “We will not bring back WorkChoices.” It repeats: “WorkChoices is dead. WorkChoices is dead and any suggestion to the contrary is wrong” (with Abbott’s signature underneath).

Sometimes direct mail letters are addressed to “the Smith family” as a whole. In other cases – especially the ones on WorkChoices – they are addressed to a male in the house. Labor letters usually address people by their first name while the Liberals tend to be more formal (perhaps to convey a sense of more conservative social values and appeal to their traditionally older supporters).

Despite the fact that the Australian National Audit Office recommended Australians should be told when they are paying for direct mail, only sometimes do incumbents reveal on their letters that they have paid for them using their printing and communications allowance.

On the plus side for democratic participation, major-party candidates in many of these marginal seats invite voters to “please contact me at any time if you wish to discuss issues…” In one letter, Christopher Pyne in Sturt says, “How can I help?... It is my privilege to serve as your federal MP. Please don’t hesitate to contact my office.” And he sent out two letters about public meetings he would be attending, inviting voters to come along. In my safe seat, I’m still waiting for any similar invitations… •

Thank you to all the readers who generously took the time to send in their direct-mail letters to Inside Story. Mail received up to 5 August was sent from the following marginal seats: Macarthur (NSW), Macquarie (NSW), Robertson (NSW), Gilmore (NSW), Solomon (NT), Swan (WA), Herbert (Qld), Corangamite (Vic), Hasluck (WA), Bowman (Qld), McEwen (Vic), Paterson (NSW), La Trobe (Vic), Hughes (NSW) and Sturt (SA).