The cemetery wasn’t our main destination. My son Eddie and I had left Hobart that morning and travelled up the Midland Highway through Ross and Campbell Town as far as Powranna (population twenty-five), where we took the backroads through the little towns of Cressy and Bracknell to Liffey. We were looking for the old Liffey school. But we also knew from the map we’d bought in Hobart that there was a cemetery in Liffey, and I absolutely cannot go past an old cemetery without pausing for a look.

I grew up in Hobart, but I had never been to this part of Tasmania before. Liffey is a very beautiful place, not a town but a cluster of small farms following the valley of the Liffey River. The cemetery is clearly marked on the map, but on the ground a cemetery without a church is an easy thing to miss. Suddenly, a glimpse of white showed above the tall yellow grass — white where there shouldn’t have been any white. We pulled over.

The cemetery’s double iron gates have crosses worked into them, signalling that this is consecrated ground. A lichen-encrusted sign tells us that the Mountain Vale Methodist Church occupied the site from 1867 until 1952. Behind us was Mountain Vale Hill, and across some green paddocks to the west, rearing up grimly on the other side of the Liffey River, were the densely forested Cluan Tiers.

We stomped through a patch of long grass and Scotch thistles, where the church must have stood, and past the remnants of a paling fence. The white headstone we’d seen from the road turned out to belong to Bertram Henry Saunders, who died in 1906 aged nineteen, and his sister Lily, who died in 1910 aged twenty-eight. Inscribed on their headstone is a pair of clasped hands surrounded by leaves and flowers. We could only see about twenty marked graves, none more recent than the 1930s. All were humbler than the tall marble headstone dedicated to young Bertram and Lily Saunders reaching out above the grass to beg passers-by that they not be forgotten.

Saunders. I knew the name. I’d been researching the impact of the first world war in this district and I knew that five men named Saunders had enlisted from around here, and that they feature on local war memorials. Bertram and Lily must have been from that family.

War memorials were why we had come. I had written an article about memorial tree-plantings in Tasmania’s northern midlands. Our visit to Liffey was to take some photographs of trees planted in 2015 at the old Liffey school to replace those planted in 1918 in honour of the men from Liffey who had volunteered for war. That done, we’d be on our way. We were snatching a few days’ holiday over Easter and would be spending that night in Longford.

But you can’t stand in an old cemetery, as we were doing, and not wonder about the entire history of the place and the people, and whether, after all, war was the defining event in their lives. I could see by the dates that these must have been some of the first white settler families in this district. Some had sent grandsons and sons to the war; others — whose names I did not recognise from local war memorials — had obviously not.

Anzac has narrowed our focus too much. It reduces our questions to those that treat the war as an inevitability. But it was not inevitable for Bertram and Lily, who died before 1914. These young people died quite innocent of one of the twentieth century’s great tragedies. The war, so soon to grind itself into Australia’s national psyche, never happened for them.

Glancing up and around, I had an uneasy sense that there were stories folded into those hills that it might not be my business to pry into. And yet I was so desperately curious about these people I would gladly have got down on my knees, right there and then, and scraped though thistles and bare earth if only that would reveal their lives to me. It wouldn’t, of course. I would have to wait until I got home to Canberra to dig into the traditional historical record.

But the experience of being in a place allows us to shift our gaze. What else happened here? How did the land and environment shape people’s ambitions, work and family life? Investigating this might produce histories that don’t sit comfortably with one another.

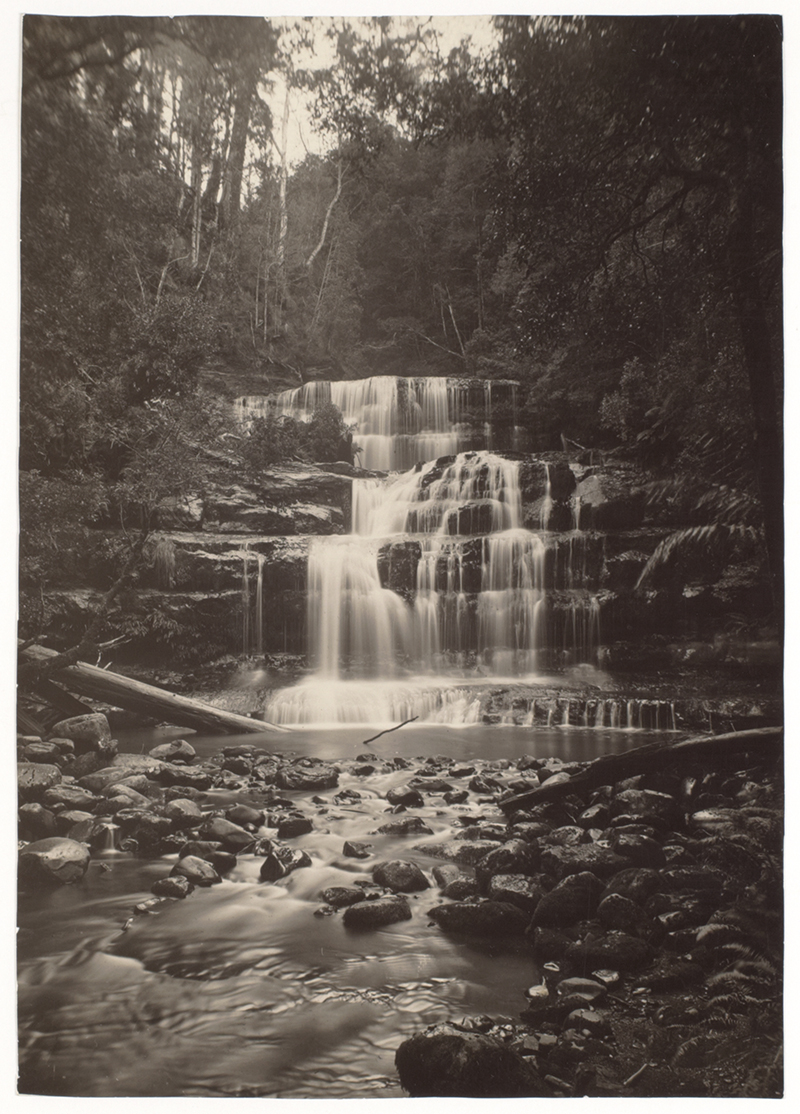

Victoria Falls, one of the four waterfalls on the Liffey River, c. 1940–50. State Library of Tasmania

The headwaters of the Liffey River gather in Tasmania’s Great Western Tiers and take a wild course through rainforest before plunging down four magnificent cascades known collectively as the Liffey Falls. The river is close to the boundaries of three nations of Tasmanian Aboriginal people, and several clans within these nations made seasonal journeys through the area. The Pallittorre clan of the North nation was based at Quamby Bluff, not far from Liffey Falls.

On 24 June 1827 a group of Pallittorre people camped between the Liffey Falls (then known as Laycock Falls) and Quamby Bluff, a prominent nearby mountain peak. They woke late in the evening to the barking of their dogs. Their fires had revealed their location to five white settlers — two soldiers, a police constable and two stockmen — intent upon reprisal for the murder the previous day of a white stockman, William Knight. The settlers fired on the Pallittorre people as they ran into the bush.

Depositions given the following week in Launceston by two of the settlers stated that only one round was fired on the Aboriginal people (many more on their dogs) and that one person had been wounded. But the Hobart Colonial Times reported — almost gleefully — that up to sixty Aboriginal people had been “killed and wounded.” Historians who have studied the incident accept that a massacre took place, with more killings on both sides in the ensuing days, part of what historian Lyndall Ryan has called an “eighteen-day killing spree” in June 1827.

The Pallittorre survivors may have been too frightened to return to the killing sites to observe funerary customs over the dead. Their normal practice was to cremate bodies, but fires would have given away their location. Without these rites, the spirits of the dead would never rest. In later years, stockmen and timber cutters passing through might have heard stories about the killing of the “Blacks,” might even have found a few bones here and there. Today, no memorials mark the sites near Liffey where the Pallittorre people died.

By the 1860s land outside Tasmania’s central midland corridor had been opened up for closer settlement. In Liffey, one of the first white arrivals was James Green, and it was he who donated a sliver of land for the building of the Methodist church in 1867, naming it Mountain Vale after his own property. Timber for the church was cut at his steam sawmill. The structure was so austere you might almost mistake it for a barn, not a church. A flourishing community grew up around it, and every year, for many years, Green gave his workers a day off so that they and their families could celebrate the founding of the church.

Mountain Vale Methodist Church, date unknown. Churches of Tasmania

Most of the blocks sold or leased in Liffey were just a few hundred acres each, and located in difficult country. Fertile certainly, but densely timbered, wet, very cold in winter, and remote from markets for the settlers’ produce. Clearing enough land to establish a viable farm could take a lifetime, but landholders were at least entitled to vote in local and colonial elections, which gave them some say in the sort of society they wanted to live in.

Until then much of the colony’s best land had been granted to free immigrants with plenty of capital who had used convict labour to establish vast pastoral estates. But now, new generations of settlers were pushing into “new” country and helping to level out old social inequalities.

The Saunders family were among that cohort. There were two couples: Caroline and John Saunders, and Maria and William Saunders. Caroline and Maria were sisters, and their husbands were probably cousins. Such couplings were not uncommon. Caroline and Maria’s parents, Jane and John Jones, had taken up land in Liffey in 1863. John was killed by a falling tree while he was building a house for his young family.

Caroline and John Saunders married in 1881 and had ten children. Eventually they did well enough to build a six-room farmhouse, quite fine for Liffey then, which they called Silverburn, but like many bush families they probably started out in a simple timber hut. With too many people living in unsanitary conditions, disease was common. Rose, their third-born, died of typhoid in 1884 at just ten months. She was probably buried in the Mountain Vale cemetery under a simple wooden cross, but if so, the grave marker is long gone.

Bertram and Lily at least survived to adulthood. I don’t know what carried them off, Bertram in 1906 and Lily in 1910. Tuberculosis perhaps. By then, the Saunders parents could afford an elaborately carved headstone for them. Unusually for a woman of twenty-eight, Lily was unmarried.

War came. Caroline and John still had four sons, and all enlisted. Leslie and Colin had moved to Queensland and were living in Gordonvale, a sugar-growing town near Cairns, when they signed up in August 1914, only weeks after war was declared. Both were at the Gallipoli landing on 25 April 1915. Colin went missing that day, but his death was only confirmed for his parents eighteen months later. Leslie survived Gallipoli but was killed in France in August 1916. Neither man’s remains were ever found; they are commemorated on memorials at Lone Pine, on Gallipoli, and at Villers-Bretonneux.

Their younger brother, Alan, enlisted from Tasmania in March 1915 and managed to have himself transferred to the same battalion as his brothers, presumably to be closer to them. After a few months on Gallipoli he joined the fighting in France. After Leslie’s death, Alan requested and was granted a compassionate discharge from the army on the grounds that his parents had lost two sons and were partly dependent on him as the only son left. He arrived home in Liffey in November 1916.

But here’s the twist. Alan had not told the truth. He was not in fact the last surviving brother in the family because all along, his oldest brother, Walter, had been living in Bracknell with his wife and four children. Walter did eventually enlist, in late 1917. He made it to France just before the armistice, when it was too late for him to see much action, and returned to Tasmania unscathed in October 1919. He took up a soldier-settlement block near Longford, and had four more children.

You can learn a lot from archival records and local newspapers. That’s how I put this story together. But there are limits. Often you can uncover “what happened” — or some of it — but not “why.” The emotional coherence that once held people’s decisions together is lost.

For instance, Leslie and Colin had left Tasmania before the war to strike out in Queensland. Why? Was there a family argument? Perhaps they were looking for work, which is why most young people leave Tasmania, but perhaps they just wanted to get out of this remote, tight-knit community where everyone seemed to be related to everyone else. But why go so far, to a place so different?

Young Alan seemed a troubled soul. He rushed to the war when, at age twenty, he still needed parental permission to enlist, but after his brothers died he lied his way out of the army to get back home again. Did his family connive at this? Given how long it took for letters to travel between continents, I would say not.

Clearly this was a family in acute emotional distress. How did Alan explain his return? What was said around the kitchen table at Silverburn in late 1916? None of us can suggest Alan was a coward. We weren’t there. But the fact that no one in authority checked his story (for instance, by requesting information from the local police) suggests that Alan may not have been an effective soldier, and that the army was willing to quietly let him go. Did his older brother Walter know of Alan’s duplicity? If so, it must have placed Walter in a most dreadful position. Perhaps — here’s a thought — the decision to volunteer for the war was more agonising for Walter than his actual experience.

The postwar years brought fresh worry for Caroline and John. In 1921 their oldest daughter, Beryl, died, leaving her own three children to Caroline and John to care for. Alan married and had a daughter but in the mid 1920s he and his family moved to Queensland, to Gordonvale, where his brothers had lived before the war. He died there in 1930, of war-related illness according to his family. He was thirty-five.

Caroline Saunders died in 1926 aged sixty-two. When John died in 1937, aged seventy-nine, he had been predeceased by seven of his ten children. The three who were left buried their parents next to their sister Beryl under a single, unadorned headstone at Mountain Vale, and added the names of their solider brothers — Leslie, Colin and Alan — who had died “For King and Country.” Thus were these adventurous, impetuous boys brought home to rest with their family.

Social historians of the first world war invariably point out that bereavement in war — the scale of it, the shock of it, and the fact that relatives could not be present at the death or bury their dead with traditional rites — was not the same as in peacetime. It isn’t natural that adult children should die before their parents. All true. And yet if we go back before 1914 we discover that many people were already in mourning when the war broke out. Each of my two Saunders couples in Liffey lost three children before 1914, and that can hardly have been a unique experience.

Maria and William Saunders married in 1886 and also established a farm in Liffey, and had eleven children. In 1901, diphtheria broke out among children in Liffey. This bacterial infection, transmitted by coughing and sneezing, was made worse in small houses where children shared cots and beds. It attacks the respiratory system; if unchecked, a toxin creates a thick grey film in the nose and throat. Many victims who die are unable to breathe.

In the space of a week, Maria and William watched three of their children die in this way: Stanley, aged nineteen months; Horace, thirteen years; and finally baby Grace, only a few months old. All three received separate funerals at Mountain Vale. Three times a procession set out from the Saunders’ house to travel a few kilometres on foot, surrounded by forest, behind a horse-drawn hearse to the little wooden church at Mountain Vale. Nothing marks their graves now.

Not surprisingly, Maria and William sold up and moved. They had more children, and were living in Hadspen, near Launceston, when war came. They had lost two sons who might have volunteered for the war, but still had three eligible sons, Harold (known as Errol) and twins Lawrence and Clarence. These young men would have had plenty of friends who rushed to the colours — including their own Saunders cousins — and yet they hesitated.

Many did. In Tasmania the enlistment rate among eligible men was 37.8 per cent. Pragmatically, men weighed up their various duties and obligations, calculated the pay and allowances made to soldiers and their families, and decided not to go. Others attempted to enlist but were rejected on medical and other grounds. But that left huge numbers who never went near a recruiting depot.

Tasmania voted twice in favour of conscription, in the plebiscites of 1916 and 1917, but the debate was bitterly divisive. For those who stayed home it must have taken a particular sort of courage to accept that their lot would be to plant potatoes, mend fences and get the harvest in; that they would be shooting rabbits and possums, not the beastly Hun.

Under the weight of all this, only Lawrence went. He enlisted in October 1916 and served on the Western Front until he was killed in action in Belgium in February 1918. He is buried in a cemetery near Ypres. Clarence, his twin brother, stayed home, married and had a family, and lived a long and outwardly uneventful life. There are tales aplenty of twins who enlisted, fought and died together, but these two didn’t. How did they decide who would stay and who would go? Could it possibly have come down to the toss of a coin?

The more we attempt to dwell inside the lives of people in the past, especially ordinary people who leave little trace of themselves in the historical record, the more questions we uncover that elude easy answers. So be it. My stories from Liffey are fragmented and unresolved. But small stories inspired by encounters with local places often ask us to reconsider broader national narratives: Anzac, or something else that we cherish. They nibble away at accepted versions of history and propose new relationships between apparently disparate experiences.

Who is a hero and who is a coward? Who is remembered and who is forgotten? How is the memory of the dead to be preserved? That man with a gun — that man with a spear — is he a patriot or is he a criminal? These binary questions are probably not useful. What is important is that we are attentive to whatever unquiet stories the land might reveal. •

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of historian Dr Shayne Breen in the preparation of this article.