On the first Sunday of each month the artists of Bundeena, south of Sydney, open their studios up to the public. There are dozens of them, working in various media. Among the painters are Shen Jiawei and Wang Lan, he originally from Shanghai, she from Beijing. They have been married for more than forty years, the greater number of which they have spent here, in a suburb flanked by the sea on one side and National Park on the other. It seems a long way from Jiamusi on the Sino-Russian border, where they first met.

It’s not easy for two artists to live together, says Wang Lan. The oeuvres and no doubt the working styles of these two painters have little in common. Her paintings are of relatively modest proportions: she has been working for years on a series called Harmony. His paintings are much larger on average, taking up not only more physical space but also, perhaps, a bit too much space in their shared lives. A few years ago, they built a new house to accommodate them.

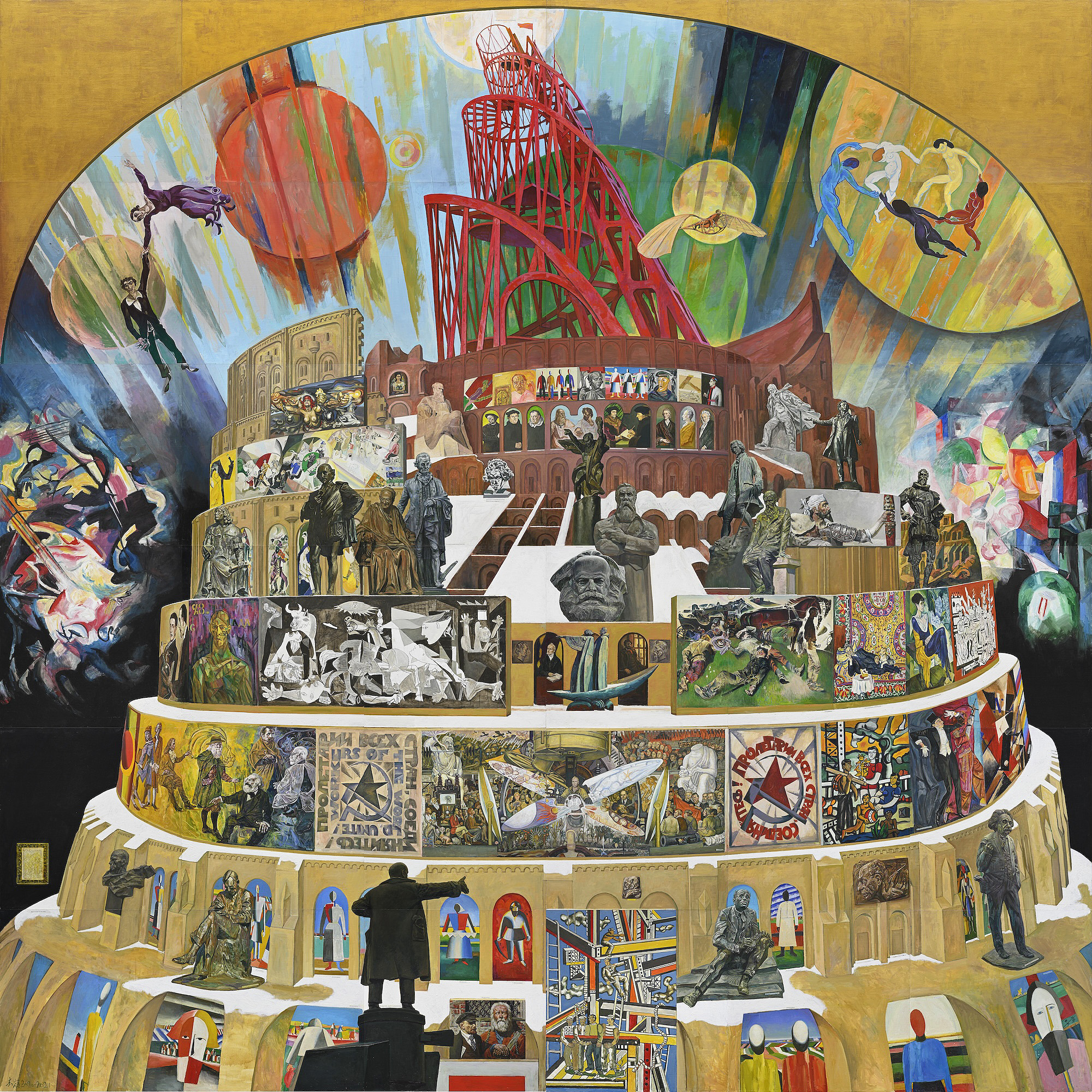

Taking up one whole wing of the house is a single work, Tower of Babel. James Bradley’s documentary, Welcome to Babel, winner of the 2024 Sydney Film Festival’s Documentary Australia Award, focuses on the production of what is a vast graphic history of communism in the twentieth century. A theme further from harmony would be difficult to imagine.

Bradley’s fine documentary locates Tower of Babel’s theme in Shen’s own history. Both Shen and Wang grew up in Mao’s China, although in very different circumstances. Her childhood and youth were traumatic, a consequence of her parents’ political status as “rightists.” He was the son of party members and eventually a party member himself. She spent the Cultural Revolution doing backbreaking work in the Great Northern Wasteland. He spent it honing his skills as an artist. He protests on camera that he also did hard labour, but she scoffs. His three months of felling trees can’t compare with her nine years of clearing land and digging trenches.

Shen was self-taught in the first instance but early showed an uncanny ability to take a likeness. In the age of the propaganda poster, such talents were in demand. His signature work from the Cultural Revolution years is Standing Guard for Our Great Motherland, one of the best known artworks of the era, now hanging in a Shanghai gallery. A figure painting, it shows three PLA soldiers guarding a lookout post on the Sino–Russian border. Shen entered it in the 1974 national art exhibition and it subsequently made its way all over the country in the form of single-leaf prints.

The rollercoaster of political and social change in 1980s China brought the couple to Australia. Shen came first, arriving in January 1989 with plans to stay no longer than six months. A pregnant Wang stayed behind in Beijing, which between April and June was in a ferment of political unrest. On 4 June, she was in hospital with her newborn and saw the injured and dying being rushed in from the carnage taking place around Tiananmen Square.

Shen quit the party and stayed in Australia, one of the many to be given refuge by Bob Hawke following the events of 4 June. After the family was reunited in 1991, Wang worked in humble jobs to put food on the table and Shen painted portraits on the street for the passing tourists. In strange contrast to Standing Guard, the painting that first made him widely known in this country was Mary MacKillop of Australia, a work prompted by an art competition held to mark MacKillop’s beatification in 1995. He won the competition and took home twenty-five thousand badly needed dollars.

These details of life and painting in China and Australia emerge conversationally in a documentary that strives to show rather than tell. Lan speaks; Shen speaks; an old friend, the painter Li Bin, pays a visit from China and also speaks. News footage is used to tell the story of the more distant past. The audience is provided with relatively unmediated insights into the world and worldview that led Shen to his project.

The documentary was a long time in the making: Bradley started filming in December 2012, when the work itself had long been in gestation. An unfinished painting of 2004, The Tower of Babel, marks Shen’s first engagement with his subject, which is not to do with the origin of languages but rather with the cataclysmic outcomes of reaching for the sky, or in this case for world revolution. The lower part of the painting is instantly recognisable as Bruegel’s Babel and the upper as Tatlin’s Tower, the latter symbolising the utopian aspirations of the Soviet Union’s early communist leadership. Shen’s own signature work, Standing Guard, appears in tiny silhouette on the lower right of the Tower, as if in testimony to his complicity in an undertaking that ended in unmitigated disaster.

Reproduced on a much larger scale, minus the Standing Guard detail, the dual-tower complex became the centrepiece of the final work now on show in Bundeena. Shen’s Tower dominates the panel named “Utopia.” There are three other panels: “L’Internationale,” showing twentieth-century artist and intellectuals amassed alongside the key political actors of the communist world; the “Gulag /ГУЛАГ,” depicting the suffering brought about by revolution and exposing those who stood by and watched it happen; and “Saturnus,” showing the revolution eating its own children.

The individual pictorial elements in the murals are almost entirely derivative: 400 recognisable faces and figures are drawn from existing, mostly well-known photographs or portraits. Picasso’s precisely drawn Homage to Guernica appears in one panel (Utopia), Guttuso’s crucifixion in another (Gulag). But there is also artistic intervention. Stalin holds a pickaxe, ready to slay Trotsky. Lei Feng, often pictured with needle and thread, is holding a gun.

The early frames were created before the couple’s new house was built. Shen had to stack them against the wall, like pieces of an enormous jigsaw cut in the square. An aerial shot shows their journey from the old house to the new in 2019: the faces of Lenin, Trotsky, Rosa Luxemburg, Chen Duxiu, Ho Chi Minh and Freda Kahlo look up into the sky from atop the roof-rack of a blue sedan rolling along a suburban road.

It is hard not to see this extraordinary work as autobiographical, at least at one level. In the Q&A following the film’s preview in Melbourne, Shen described himself as a man of the twentieth century. His encounter with the West, first via books, including art books, and then in person, plainly produced a decentred vision of that century. In the crowded canvases that make up Tower of Babel he summons up ghosts of twentieth-century communism from across the face of the earth. He pointedly identifies the fellow travellers: the intellectuals and artists who enthusiastically or tentatively or even critically participated in a process that shaped his own life and times. It seems that he has desired to stand atop the century that produced him and deliver judgement on it.

Wang Lan says that Shen is able to contemplate this history because he did not suffer from it. She herself cannot bear to dwell on what happened. •