The Anzac weekend gave us a taste of what subdued commemoration looks, sounds and feels like, but the muted mood in the week of the 250th anniversary of the Endeavour’s arrival into Kamay Botany Bay still surprises. Who would have thought it would be like this?

Not so long ago it was unclear whether Australia had the appetite — or wherewithal — to celebrate Cook again. The “statue wars” were a reminder that the weeping sore Cook symbolises is far from healed. As Stan Grant’s incisive essay argued, Cook will remain a lightning rod for as long as Australia’s assumptions about discovery, possession and sovereignty are allowed to stand shamelessly unexamined. He called for a clear-eyed national conversation, and what we got instead was a furious backlash from some quarters and tip-toeing around the issues from others, including our prime minister at the time.

That little taster of what happens when Cook is criticised suggested that perhaps we were still not quite ready as a nation to commemorate the Endeavour’s voyage along the east coast — or at least to grapple in a good or proper way with the unresolved issues that lie at our colonial core and have adhered to that expedition’s captain.

Nevertheless, as the sestercentenary of 1770 inched closer, and particularly after the revolving door of prime ministers stopped with the Member for Cook, Scott Morrison (a more apt title is hard to imagine), it became a sure thing that 2020 would be the Year of Cook. Morrison, like his predecessor Bruce Baird and many earlier Members for Cook, is an admirer of Lieutenant James Cook’s character and achievements, and a defender of his central place in the nation’s history.

Morrison has made no secret of his idolisation of the man, but it made him a soft target. Back in the distant past of late last year, when he was besieged for taking an overseas family holiday without telling the Australian public or the media, a joke did the rounds on social media: “What do Captain Cook and the Member for Cook have in common? They both regretted going to Hawai’i.” Boom boom.

Soon after assuming office, Morrison committed nearly $50 million to commemorate the quarter millennium of the Endeavour voyage. The announcement was seen by many, particularly younger Australians, as an outdated indulgence. Criticism only intensified when it was announced that a good portion of the money would support the circumnavigation of Australia by the replica Endeavour, which the National Maritime Museum in Sydney looks after. To remain seaworthy and keep its crew credentialed, the replica needs to sail regularly. Although this is an expensive drain on its cash-strapped host, the opportunity to put the little ship to sea was welcomed; and there were plans for educational activities, community engagement and exhibitions at each of its stopovers.

The voyage might also have prompted protests, or at least alternative accounts of its meanings, in the places where it pulled ashore. Certainly, its travels in real time would have generated a stream of images and stories for a hungry media and would have stretched the commemoration from a single moment (usually the first landing at Botany Bay) into a four month (or 126-day) epic punctuated by episodes, encounters and experiences.

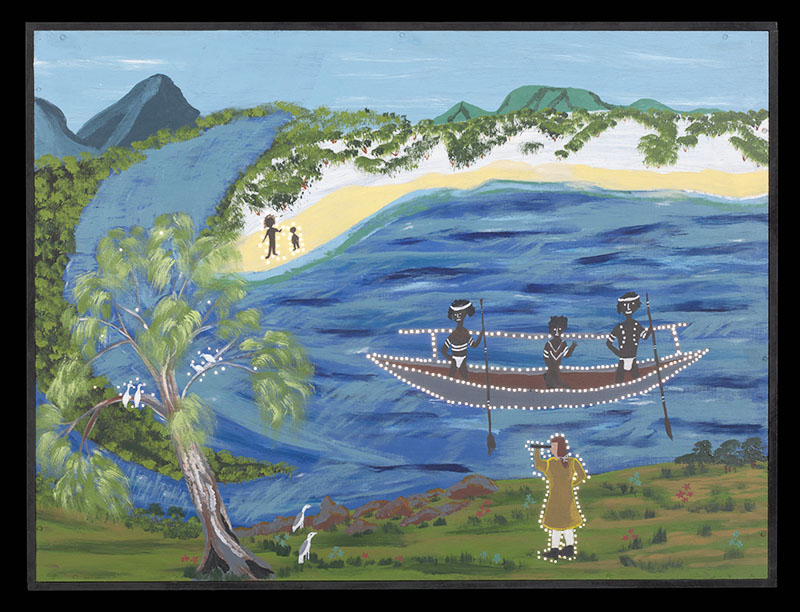

Three Bama in a Canoe (2019), by Wanda Gibson of Hopevale. Endeavour Voyage exhibition/National Museum of Australia

But the problem of commemorative history, and the rock on which this enterprise faltered, is that it requires a certain faithfulness to the known “facts” even as its metier is to stretch history to fit our contemporary desires. And so, when the circumnavigation was billed as a re-enactment, that pact was broken: Cook didn’t circumnavigate, and cynicism filled the space that opened up.

Now the pandemic has kept the ship moored in Sydney, scotching a key component of the planned commemoration. And, like dominoes, local festivals, events, and exhibitions along the coast have fallen over too. The annual festival at Cooktown, which has been growing and garnering interest over the past decade, will not go ahead this year, a blow for those who have worked in a largely voluntary capacity for many years and for those who were planning to make their way to Cooktown to attend. Held in June, it is the biggest weekend on the town’s calendar and local businesses depend on it.

A lesser-known component of the federal funding package is the Cultural Connections Initiative, which is being coordinated by the National Museum of Australia. It supports “professional development and employment opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural practitioners and grassroots cultural work.” Over the last two or so years, the Museum has worked with nine organisations dotted along the east coast to co-design and create cultural, art and language programs and activities.

Pre-pandemic, the idea was that — as the replica Endeavour made its way north — some of this very powerful local community work and storytelling would have come to the fore, but the program itself was never conceived as providing content for public commemoration. Rather, the NMA is pursuing a bigger and more ambitious engagement with Indigenous Australians, one that both contributes to and reflects changes in museum practice worldwide. This involves seeking ways to contribute to the work that communities do, or want to do, in researching, telling, curating (broadly speaking) and sharing their own histories (again broadly speaking) in their own ways, and it necessarily includes some commitment to employment and training.

The NMA’s Encounter Fellowships program, which emerged from the landmark Encounters exhibition held over late 2015 and early 2016, is also a key component of this longer-term vision. Using a portion of the windfall that came with Cook’s anniversary, the NMA has provided resources to some east coast communities to realise their own local visions and ambitions around cultural heritage and knowledge, whether it references James Cook or not.

Importantly, the Cultural Connections Initiative has been rolled out at a remove from the engine room that drives the development of Museum’s own Cook show. Exhibitions have a momentum that can run counter to the usual rhythms of time. But in commemorative-style history, they still matter. The package of funding from the federal government came with the expectation that both the NMA and the National Library of Australia would do public shows. Opting to go early before the calendar of commemorations became too crowded, the NLA opened its Cook and the Pacific in late 2018 with a very droll speech by Sam Neill.

In the meantime, the National Museum of Australia was developing its exhibition, Endeavour Voyage: The Untold Stories of Cook and the First Australians, which would have been launched earlier this month if Covid-19 hadn’t intervened. The delay brings to mind Cook’s moral crisis when he suspected that his crew was responsible for introducing new and fatal diseases, and his own attempts at managing and mitigating the situation. “As there were some venereal complaints on board both the ships…” he wrote during his third voyage

I gave orders that no women on any account whatever were to be admitted on board the ships, I also forbid all manner of connection with them, and ordered that none who had the venereal upon them should go out of the ships. But whether these regulations had the desired effect or no time can only discover. It is no more than what I did when I first visited the Friendly Islands yet I afterwards found it did not succeed.

The Untold Stories exhibition is instead being presented online — an impressively agile response from the institution, and particularly from the small curatorial team behind the exhibition, who could have been forgiven for thinking that all the hard work and long hours were behind them and they could bathe in visitors’ responses and the media coverage of their intellectual and creative labours. Instead, they are scurrying to transform a feast of old and new art and objects, many produced for the show or borrowed from overseas institutions, and immersive audio-visual programs designed to fill a single physical space. As has become a standard response, there are positives and negatives to be found in this new reality.

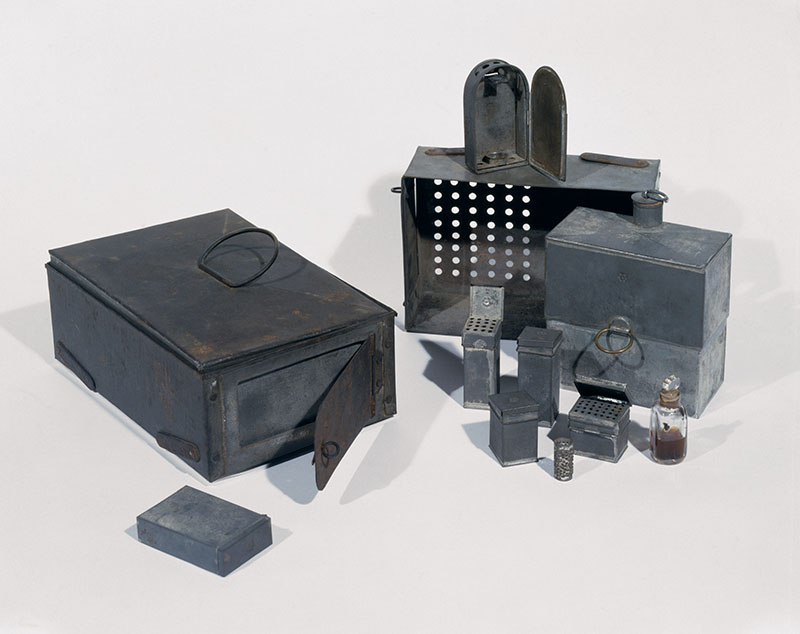

Joseph Banks’s travelling stove, used on the Endeavour 1768–71, on loan from the Royal Geographical Society. Endeavour Voyage exhibition/National Museum of Australia

As the virtual exhibition follows Cook’s voyage up and the coast, visitors are being drip-fed video and other content, a decision that was presumably as much pragmatic as pedagogical. But it has the welcome upside of helping us to keep track of days, something we are all struggling to do. It’s 29 April, must be time to land!

(This inspired me to suggest to my family that we do daily readings from Cook’s and Joseph Banks’s journals as a way of marking the days, but I was met with uncomfortable silence and probable eye-rolls. Much more enthusiasm has been generated by a virtual road trip in the United States, a holiday my sister had planned but has been cancelled. We’re currently “in” San Francisco.)

The Untold Stories exhibition’s itinerary is composed of nine significant sightings or encounters on shore. We start at Point Hicks on the Victorian coast, where land was first sighted, and end at Possession Island on the far northern Queensland coast, where Cook made his controversial claim over the territory. At each site, the stories of the people, places and prominent landmarks that he saw, described and renamed are told by local Aboriginal people.

Along the way, we learn about important cultural sites (often mountains which Cook had described and renamed), about what the people on the shore thought the ship and its crew were (pelicans, possums, ghosts) and what has happened in its wake (violence, missionisation, assimilation, and survival). So far, only Point Hicks and Gulaga (Mt Dromedary) on the south coast of New South Wales have been revealed. Come Wednesday, we will be in Kamay Botany Bay sharing the “untold version” of the much-told story of the famous first landing.

With its emphasis on Aboriginal communities telling their own stories, the exhibition follows an approach the NMA has honed over the last decade or so in a trio of major exhibitions: Kaninjaku: Stories from the Canning Stock Route, Encounters, and Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters. And like those exhibitions, innovative and immersive audiovisual elements are central.

For the Untold Stories exhibition, the NMA commissioned Alison Page and her creative partner Nik Lackaiczak to create a film with four communities along the coast. The result is The Message, which imaginatively and impressionistically reconstructs a story about how knowledge about the Endeavour’s arrival was passed from group to group all the way along the coast. In this retelling, the British appear as only shadowy figures; it is Indigenous people’s faces, languages, places, objects, dress, knowledge, ceremony, communication and social worlds that occupy the frame.

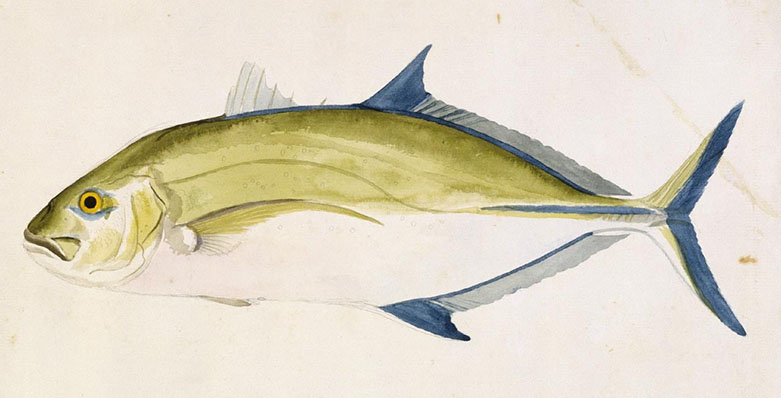

Caranx melampygus (blue trevally) by Sydney Parkinson (1770), © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London. Endeavour Voyage exhibition, National Museum of Australia

The Message uses a form of visual storytelling that comes without explication. Language and song are pronounced, body gestures are used in place of speech, dances and displays of strength are shown. There are no subtitles and there is no voiceover explaining what is happening on the screen. Some viewers will recognise certain vignettes, but it is not narrative. In a “making the film” blogpost, the filmmaker explains that “the temptation for all of us was to approach this like a drama — a straight telling of the story to dispense with obscurity and make the history clear,” but they eschewed this in favour of producing a piece to:

encapsulate the emotional symbolism of the chapters of the story. Like Aboriginal painting, the meaning takes deep diving to fully understand all its layers. While some of the scenes will reflect historical perspective and records, our main aim was to engender a visceral and emotive response through a highly engaging and sometimes challenging visual narrative.

Interpretation is left open-ended, and the more cryptic elements would probably have been filled in by other parts of the physical exhibition. Not straight narration, the point of the film is as much the process of making it in collaboration with the communities who live under the shadow of Cook. It is not designed to replace one version of Cook with another. Watching it at home on a tiny laptop with a tinny speaker, I was conscious that its fully immersive quality — of creating another space in which to encounter Cook and his history — was dissipated. (I’ve heard of other visitor’s computers delivering a much better exerience.) It will be good to eventually see it in the space for which it was designed.

I’m looking forward to today’s instalment of the exhibition, which is at Kamay Botany Bay; but then I will have to patiently wait for the next instalment, which is scheduled for 12 May when the Endeavour passes the three mountains on the mid-north NSW coast and that Cook named The Three Brothers, but which are known in the local language as Dooragan, Mooragan and Booragan.

Between the more exciting moments, days pass. We sit it out at home, and the parallels with shipboard life start to suggest themselves. We follow daily routines, spend time doing chores, get lost gazing into the distance, and try to manage our emotions. Accounts of Cook that are only interested in heroics or cross-culture encounters can eclipse the sheer monotony and drudgery of voyaging. And they can also miss the heightened emotions that come with living with others in confined spaces.

The fifth place on the Untold Stories exhibition’s itinerary is Gooragam – Bustard Bay, Seventeen Seventy which we will visit on 23 May and where we are told:

The Endeavour dropped anchor here and a small crew prepared to make their second landing on Australia’s coast. By the time they landed, they found only footprints of Gooreng Gooreng people and their abandoned fires.

This might seem a little anticlimactic, but it gives another opportunity to learn something about that place and its people.

HMS Endeavour Ship (2019), by Kurt Kynuna. Driftwood, pearl shell, galvanised wire and screws. Endeavour Voyage exhibition, National Museum of Australia

What will probably not be covered, or not in any detail, is what had happened on board the Endeavour immediately prior to this. Overnight, as Cook recorded in his journal entry for 23 May, his clerk’s clothes and ears had been cut off while the man slept in a drunken stupor. As Cook wrote:

Last night sometime in the Middle Watch a very extraordinary affair happened to Mr Orton my Clerk, he having been drinking in the Evening, some Malicious person or persons in the Ship took the advantage of his being drunk and cut off all the cloaths from off his back, not being satisfied with this they sometime after went into his Cabbin and cut off a part of both his Ears as he lay asleep in his bed.

The episode clearly disturbed him, and he devoted an unusually large number of words in his journal to trying to make sense of what had happened, who was at fault, and what its implications were — including for his own authority. The entry ends with Cook deciding to keep quiet, for fear of escalating the situation, until the culprits were known:

I shall say nothing about it unless I shall hereafter discover the Offenders which I shall take every method in my power to do, for I look upon such proceedings as highly dangerous in such Voyages as this and the greatest insult that could be offer’d to my authority in this Ship, as I have always been ready to hear and redress every complaint that have been made against any Person in the Ship.

The episode is important, not just for what happened (as intriguing as that is) but because it reminds us that when we attempt to interpret the history of the Endeavour voyage — from the ship and the shore — we are faced with trying to comprehend many different and unfamiliar cultures, values, personalities, and contexts.

Untold Stories takes us a long way into seeing, experiencing and understanding the deep and complex cultural worlds into which Cook and his men occasionally stepped when they went ashore. In another iteration, such an exhibition might also attempt to try to better understand the puzzles that Georgian shipboard life represents, and the cruelty and pettiness of men living in close quarters that even Cook sometimes found difficult to fathom and manage. At this present time, it is those other untold stories that are also speaking loudly to me — and perhaps to Scott Morrison as well. •