This week marks the fiftieth anniversary of the ABC’s current affairs program This Day Tonight, heralded in the fortnightly magazine Nation as “the first full-scale confrontation between the old-school hard news and the new school, mediated through personalities.” To mark the anniversary, the ABC has made that first episode available on YouTube.

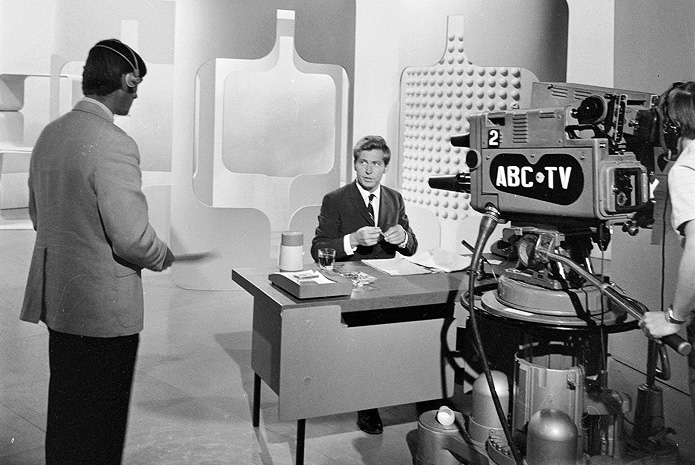

Presenter Bill Peach, already well known to television audiences as host of Telescope on ATV0 (now Network Ten) and reporter on Four Corners, perched self-consciously on the edge of the desk to introduce the premiere episode. “We’re up against some pretty stiff competition, like The Man from UNCLE,” he said, “which I guess makes me the man from Aunty…”

It took a while for the zingers to get up to speed, and for Peach to settle into the anchor role, which he occupied with growing assurance over the next nine years. Recalling that first episode in his 1992 book about the program, he acknowledged the validity of a stinging review in the Australian that complained of its “heavy-handed light-heartedness.” Among the failed comedic touches were the reading of fake “good luck” telegrams, Peach’s swinging a cricket bat to introduce an item about a test match, and his appearance in an artist’s beret in front of a giant cardboard film camera to present an item on the Oscar nominations. It was, according to Valda Marshall in the Sydney Morning Herald, “the worst opening night of any show I can remember.”

TDT also had one of the quickest turnarounds in its fortunes. The second night was tighter, tacking into the winds of controversy with a report from Mike Willesee on rumours that Harold Holt’s Liberal government was planning to exert control over the ABC by replacing the chairman with its own appointee. Allan Fraser, a reporter for the Sydney Sun and a former Labor MP, expressed concern that the metropolitan newspapers and television companies were in the hands of six proprietors, all of whom were Liberal supporters.

The repercussions were immediate. Clement Semmler, manager of the ABC, quashed plans for a follow-up report, but in Peach’s words, “TDT had found its natural element. It was in hot water.”

It took rather longer for the program to find its style and tone. Essentially, the production team was learning on the job. Of course there were examples to follow – TDT was modelled on the BBC’s Tonight and had the same title in the planning stages – but there was a need to forge a new path, to establish an Australian milieu contrasting with the still-dominant British content of news services. The self-conscious informality was also a calculated attempt to differentiate TDT from the ABC’s Weekend Magazine and the BBC’s Newsreel, which Mungo MacCallum Snr described in Nation as “suety, avuncular and wrapped in cliché.”

Anniversaries – and the half-century is a significant mark in the history of television – are quite properly occasions for celebrating our cultural heritage, and there is no question that TDT holds a distinguished position. As Graeme Turner wrote in his 2005 book Ending the Affair: The Decline of Television Current Affairs in Australia, the program became the “gold standard” against which all others in the category were measured. Yet, says Turner, when he started viewing sample tapes from the first few months of its life, he was amazed at how bad it was.

Doing my own sampling from the early episodes of TDT, I can see what he means. The training wheels are visible in every aspect, from the contrived scripts to the clunky studio layout, ill-judged camera angles and botched editing. Fluency and momentum are qualities we take for granted now in good current affairs television, but they involve forms of technical acuity, and a repertoire of visual ideas, that had yet to be acquired.

An item on prime minister Harold Holt’s Asian tour begins with reporter Frank Bennett reading from a clipboard as he walks in front of a series of panels displaying portraits of the leaders of the five nations Holt visited: Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore, Cambodia’s Prince Sihanouk, Laotian Prince Sauryavong Savang, Chiang Kai Shek of China and Park Chung Hee of South Korea. Bennett then proceeds to interview two of the press team from the tour, who make their appearance on a boxy little television in the corner of the studio.

It’s embarrassingly gauche to the eye of a twenty-first-century viewer, but the unsophisticated approach is now framed by the complexities in our own field of vision. Where the original viewing audience was watching a retrospective of “this day” and the unfolding events around it, we are watching history of several kinds: political and cultural history, and the archival history of television itself. This was a time when Mao Zedong was still leader of the Chinese Communist Party, Harold Wilson was prime minister in Britain and Lyndon B. Johnson was president of the United States. In Australia, Gough Whitlam had recently become leader of the opposition.

A tour through clips from the earlier years of TDT gives an insight into the particular qualities of archival television as a medium for exploring cultural and political history. Where historical documentaries provide us with narratives and reassembled footage of past scenes, the original television coverage reveals subtler elements – moods and tones. It’s in these moments that we learn how far we are estranged from the circumstances, attitudes and perspectives of our forebears, or even our former selves.

Many of the reports from TDT’s early years communicate a sense of the nation waking up to itself. “Australia is a quiet country,” MacCallum commented, speculating on whether the program would manage to find enough stories to fill its daily timeslot. “We seldom initiate big news.”

That was about to change, as tensions escalated around the Vietnam war, land rights disputes grew in scale and urgency, the sweeping social changes of the late 1960s gained traction and, later, the Whitlam government steered towards crisis. But when the TDT team started to pick up on these issues, the stories could seem curiously detached. It’s as if no one really has any sense of where this all might go.

A 1968 story on the land rights dispute at Wave Hill cattle station in the Northern Territory begins with a voiceover from the reporter. “The idea that the Aborigine might own some of the land he discovered 100,000 years ago is one of the rude awakenings of the 1960s.” The Gurindji, stockmen who worked on the vast station owned by the Vestey family, were making a claim for 500 square miles of land around an oasis at Wattie Creek. Under the leadership of elder Vincent Lingiari, they had acquired a supply of wire and begun fencing it off, but were stopped by a representative of the white owners, who accused them of “stealing another man’s country.” An interview with Lingiari is followed by one with the Wave Hill manager, Frank Wilmington, who asserts with confident brevity that “they couldn’t handle the land if they were given it.”

In the present media environment this situation would generate days and weeks of inflamed debate, GetUp! campaigns, and Twitter messages by the thousand. Yet, in this brief item, the ironies burn like acid. The real story is not that the Gurindji tried to reclaim their land, but that they were refused it, and by people with no rights to it, who themselves had no idea of how to manage it. Their compensatory offer was a couple of square miles of desert land which they proposed to “irrigate” – a technical impossibility.

Those things could have been said, and in any coverage of such an issue now, someone would be found to say them. Somehow they were communicated all the more powerfully for not being spoken. The injustices of the situation are radioactive.

In a story aired in 1969, reporter Bob Connolly surveys Aboriginal rock carvings in the sandstone promontories of Ku-ring-gai. There’s no notice to identify them, no cordon to prevent their being walked over, and they’re slowly fading away. A row of metal fence posts has been driven right across the centre of one of the largest rocks. David Moore, curator of anthropology at the Sydney Museum is asked for an opinion.

“We know very little about them,” Moore says, but offers the view that they were mythological carvings of Dreamtime figures. We cut to a new suburban housing development being built over the top of another series of carvings. A resident who has recently completed building seems bemused. His septic tanks are built over one of the artworks. He had asked for them to be located further down the block, but the council engineer decreed he must have clearance for a driveway, “so that’s all there was to it.”

Reports on the Vietnam war and the rising tide of protest are at first similarly tempered. A studio discussion on the demonstrations involves Douglas McCallum, professor of political science at the University of New South Wales, and Harold Levien, author of a widely read pamphlet, Vietnam: Myth and Reality. It’s a steadily managed exchanged, with Levien arguing for the effectiveness and validity of demonstration as a form of political intervention and McCallum questioning the motives of the protesters. Each shows at least some capacity to listen to the other, in stark contrast to the exchanges that take place now on 7.30 or The Drum.

In comparison with TDT, the format of these talk-based current affairs programs seems claustrophobic and overwrought. Too much is invested in the figure of the celebrity presenter, opinions become overblown, and the viewer feels trapped in an endless cycle of strident assertions.

TDT, in spite of the concerns of Mungo MacCallum and others, never did become personality-driven. If many of our most distinguished reporters made their names on the program (including Mike Willesee, Caroline Jones, Andrew Olle, Paul Murphy, Peter Luck, Richard Carleton, George Negus, Kerry O’Brien and Mike Carlton), it was for their professionalism as communicators and their tireless determination to track down important stories. As TDT got into its stride, it played a significant role in bringing critical issues to public consciousness, and contributing to changing frontiers of public opinion. •