Bob Brown, the former and still best-known leader of the Australian Greens, was arguing more than twenty years ago that the rise and rise of his party was inevitable, leading to the eventual collapse of the two-party system.

He would say that, wouldn’t he? But what was dismissed at the time as political hype is looking less improbable these days. In the dazzle of the six teals storming home (and Zali Staggall returned) in previously safe Liberal seats in last year’s election, the Greens’ achievement in increasing their numbers by six — from one to four in the lower house and from nine to twelve in the Senate — has tended to be overlooked.

Representation in the Senate fell to eleven this week with the defection of Lidia Thorpe, the first Aboriginal senator from Victoria and the Greens’ First Nations spokesperson, over her advocacy of a No vote in this year’s referendum. But the loss of her Senate spot has the upside of ending a damaging internal split over the Voice.

In Victoria, although the party’s predictions of a “greenslide” in November’s election didn’t eventuate, its representation rose from three to four in the Legislative Assembly and from one to four in the Legislative Council. In a long and continuing journey, the Greens have not so much stormed the barricades as crept up on opponents who have habitually underestimated them.

Not so long ago, winning seats in lower houses was considered a hurdle too high for independents or minor parties. The Labor and Liberal parties simply had too much of a head start when it came to exceeding 50 per cent of the two-party vote.

Not anymore. Labor is in power in Canberra with less than a third of the first-preference vote — below its losing result under Bill Shorten in 2019 — while the Coalition parties did only slightly better on primaries (but a lot worse on preferences). Increasingly it is Labor and Liberal preferences that are being distributed to independents and smaller parties rather than the other way around.

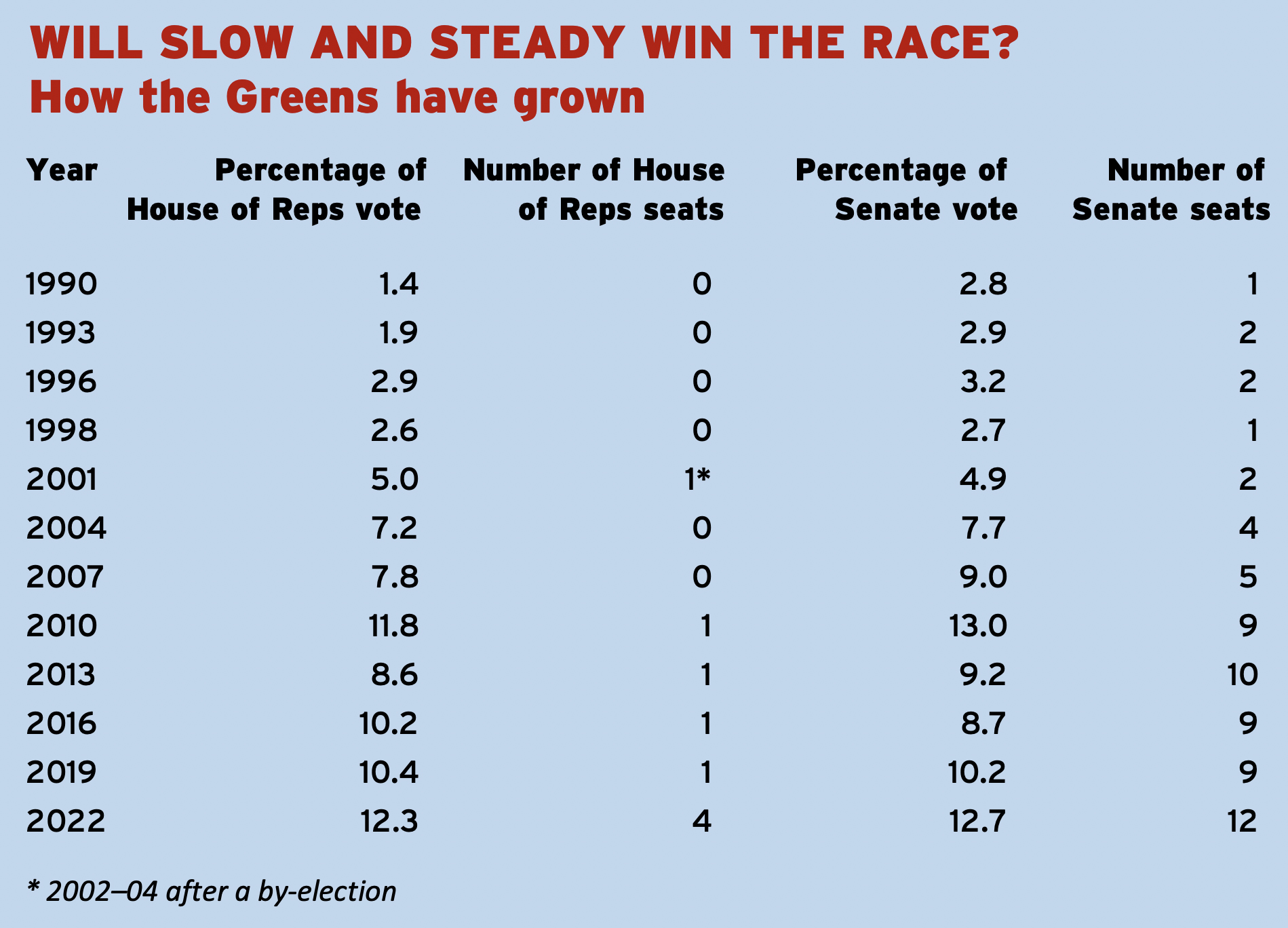

It is thirty-three years since the Greens first won a place in the Senate, where proportional representation lowers the barrier for election to 14.3 per cent in a typical half-Senate election. That was with the election of Western Australia’s Jo Vallentine, who had previously represented the Nuclear Disarmament Party in the Senate.

In 1990, the Greens’ lower house vote was just 1.4 per cent; even though environmental issues were prominent that year, it was the Australian Democrats, with 11.3 per cent in the lower house, who benefited, together with the Hawke government, courtesy of Democrat preferences.

When Brown entered the Senate in 1996, he and Dee Margetts from Western Australia were the party’s sole representatives. At the following election the party’s national vote was still only 2.6 per cent in the lower house and 2.7 per cent in the Senate. Since then, the party has been on a mainly upward trajectory, though not without fluctuations and setbacks.

A significant shift upwards started in 2001, and by the 2010 election, when climate change policy was prominent, the Greens vote reached 11.8 per cent in the House and 13 per cent in the Senate. That was the year the party broke through in the lower house, with the election of Adam Bandt in the previously safe Labor seat of Melbourne. (Michael Organ had won a lower house seat for the Greens in a by-election the Liberals didn’t contest in the NSW seat of Cunningham in 2002 but was defeated in the general election in 2004.)

Twenty-ten was also the year the Greens had their first taste of real power — and its consequences — at the federal level. Their alliance with Julia Gillard’s minority government produced an agreement on climate change measures, but the association with her increasingly unpopular administration, defeated at the hands of a rampaging Tony Abbott in 2013, rubbed off. The Greens lost more than a quarter of their 2010 vote. But they resumed their upward trajectory in the next and subsequent elections.

In last year’s election, the Greens’ vote went up to 12.3 per cent in the House of Representatives and 12.7 per cent in the Senate. Its lower house vote was a record, whereas its Senate vote was marginally below its previous high. There might never have been a better time to stand for election representing anyone other than the major parties, but the competition for the minor-party and independent vote had also intensified.

According to the Australian Election Study — the detailed survey conducted by academics after each election — 24 per cent of the people who voted for the teals in 2022 had supported the Greens in the 2019 election. That was more than the 18 per cent who had previously voted for the Liberals.

Combined with the 31 per cent of teal supporters who had voted Labor in 2019, this at least partly tactical voting put the teals into parliament. They also reduced the Greens’ overall vote, though not in the seats that mattered. To the contrary, the party boosted its numbers in the House of Representatives from one to four, with the re-election of Bandt for a fifth term, and three seats in inner Brisbane won with strong grassroots campaigns, including two taken from the Liberal National Party

On one view, the Greens have reached or are close to the upper limit of their vote, except now in Victoria. Increasing their representation in the Senate will certainly be difficult for the foreseeable future, given they already have two senators in each state. But in the lower house the argument that the party has hit a ceiling is based partly on three assumptions that are looking outdated.

One is that a vote for the Greens is wasted because they can’t win. Increasingly, in inner-urban seats, that’s no longer true.

Another is that the party is too radical and left-wing to command mainstream support. So how come it’s winning Liberal seats? Possibly because the whole notion of left and right is breaking down, at least among younger voters.

The third assumption is that the Greens can’t overcome the dominance of the major parties and their habit of stealing any of their opponents’ policies that attract significant support. That tactic is becoming much harder for the big parties because they’re shedding support at both ends: the Liberals are losing votes to the teals on the one hand, and to One Nation on the other, while Labor struggles to straddle the gap between more conservative voters in the suburbs and those attracted to the Greens in the inner cities. And then there is the Brisbane factor, where community activism and volunteering, together with a solid base in local government, means Greens are identifying better than other parties with real voters.

Demographics are also working in the Greens’ favour. Better-educated voters are more likely to vote Greens and their numbers are rising as a proportion of the population. Younger voters are much more likely to support the Greens and more likely than in the past to keep doing so as they get older, countering the effect of an ageing population. Concern about global warming has been rising among the general voting population and it has been rising more among the young.

The greatest challenge for the Greens is spreading beyond its base in the inner cities. The suburban vote is large and — combined with the country vote in the case of the Coalition — that means there is still a long way to go to replace a big party.

Not that this deters Bob Brown who, when I contacted him for an update, stuck unhesitatingly to his prediction of the Greens as an unstoppable force. “I think it is too slow, but it’s inevitable and inexorable because the old parties — Labor, Liberal and National — simply can’t change from being in favour of widespread exploitation of nature,” he says. “These days I liken it to the slowly rising sea levels: people aren’t taking notice until the next storm hits.”

If the Albanese government remains popular — a big ask for any government these days — it may be able to stave off further Greens advances. But that can’t be taken for granted. The big risk for Labor is defections by supporters who think the government is not doing enough to tackle climate change.

The Australia Institute’s Richard Denniss, who has worked for the Greens in the past, sees a particular vulnerability in the government’s position on coal and gas exports. “Labor for decades has focused on domestic emissions reductions, and they have always been slightly more ambitious than the Liberals and that has always been enough to win them first or second preferences on climate change,” he tells me. “Labor’s blind spot is supporting new coalmines and gas wells and arguing it doesn’t matter because they don’t count towards Australia’s emissions. This is an enormous opportunity for the Greens and the teals.”

The government argues that it is doing no more than following international practice in counting emissions where they are generated. But the United Nations and the International Energy Agency, among others, have said there can be no new coal and gas projects if we are to avoid catastrophic climate change. The Greens claim 114 such projects are waiting for approval in Australia.

Underlying the government’s approach is the hope that the market will get it off the hook: that falling demand for coal and, in the longer run, gas will see many projects shelved. That means it won’t bear the odium for blocking development and jobs. In the meantime it has supported the development of the giant Scarborough gas project off the Western Australian coast, although on one estimate it could produce three times Australia’s current annual domestic emissions over its lifetime.

Environment minister Tanya Plibersek said last year that it was not sustainable or reasonable in a modern economy like Australia to argue for a stop to mining (overstating the Greens’ policy of no new coal or gas projects). Besides, so goes the refrain, other countries will simply buy their fossil fuels from somewhere else.

The trouble is that the United Nations and the International Energy Agency say that’s not good enough. Particularly not, so the Greens argue, since Australia is the world’s third-largest exporter of fossil fuels and new projects will mean we miss our targets for emissions reduction.

Labor is caught politically on this issue. Stopping what has been an important source of Australia’s wealth would create a sizeable target for the Coalition, as would the risk of domestic gas shortages, though that should be avoidable. But the hypocrisy of its present policy creates the real risk of further haemorrhaging to the Greens.

The teals aren’t buying the government’s arguments either. Sophie Scamps, who won the Sydney seat of Mackellar from the Liberals, said in September it was hard to believe that “new coal and gas projects are being assessed and approved without any consideration given to the future impact that emissions from these projects will have on our environment and on our nation.”

But the Greens have their own dilemma: they need to avoid being seen as wreckers. After making loud threatening noises over the legislation enshrining Labor’s 43 per cent emissions reduction target, they ended up supporting it after securing minor concessions. Now the party is ramping up the rhetoric over the bill for the safeguard mechanism, which requires major polluters, including those opening new gas wells, to gradually reduce their emissions.

Bob Brown’s arguments about the Greens’ future notwithstanding, nothing is inevitable in politics. Independents and smaller parties have come and gone in the past. The Democratic Labor Party, formed from a split in Labor in the 1950s, maintained representation in the Senate for two decades and helped keep Labor out of office for twenty-three years by directing its preferences to the Liberals. The Australian Democrats, founded by former Liberal minister Don Chipp “to keep the bastards honest,” were a force on the centre left of politics for more than three decades. They have both faded to near irrelevance.

But the Greens are looking increasingly like a permanent fixture. Apart from their federal representation, the party has twenty-seven MPs in state and territory parliaments and more than one hundred in local government.

With growth, though, have come some of the same issues that make life difficult for the main parties. Stephen Luntz, the party’s long-serving Victorian psephologist, identifies three streams within the party: social democratic, a more radical or Marxist grouping, and a pure environmental strand. “We do best when we manage to harness those altogether,” he says. “There are times when we don’t and some members seek to push others out.”

This has been evident particularly in New South Wales (though also in Victoria), with outbreaks of factional fighting, threatened splits and resignations. In last year’s federal election, the Greens’ vote in New South Wales was 10 per cent, well below the national average of 12.3 per cent.

In Victoria, meanwhile, a brawl over perceived attitudes to transgender members escalated at the end of last year to an extraordinary threat to expel the Victorian Greens from the national party, which happens to be headed by Victoria’s Adam Bandt.

Going into next month’s state election in New South Wales, the party nevertheless has three seats in each of the two houses of parliament. The trend away from the main parties, reinforced by both the federal and Victorian elections, provides opportunities, though optional preferential voting will make it harder for the Greens to win lower house seats.

To date, the Greens have enjoyed the luxury of a party seldom held responsible for implementing its policies. Twice when it wielded real influence it suffered politically. In 2009, Labor blamed it for blocking the Rudd government’s legislation for an emissions trading scheme because it wanted something better. In 2013 it used its alliance with the minority Gillard government to negotiate significant measures to tackle climate change but was hurt by the association with a divided and unpopular Labor Party.

With more MPs in the current parliament, the Greens are walking a fine line between taking a stand against new coal and gas mines and not blocking progress on tackling climate change. The extent to which the party carries off this balancing act will help determine its future trajectory.

But the climb up the electoral mountain will get steeper as more attention is paid to Greens policies and the consequences of implementing them inevitably arouse controversy. That is the price of power. •