When Scott Morrison’s stint as treasurer enters the history books, the record will resemble Joe Hockey’s and Wayne Swan’s more than Peter Costello’s or Paul Keating’s. This will happen regardless of anything he does, and the reason is simple: economic times like these don’t make for greatness.

As the budget data shows, Costello was the biggest-taxing treasurer in Australian history, taking in a yearly average of 23.4 per cent of GDP from July 1996 to June 2007. Keating (1983–91) came second with 22.5 per cent. By contrast, from 2008 to 2013 Wayne Swan managed a miserable 20.9 per cent and Joe Hockey (2014–16) an almost respectable 22.1.

Morrison’s projected tax take for 2016–17, of 22.2 per cent, is the largest since 2007–08 but is still lower than any of Costello’s eleven (or twelve, if we give him 2007–08) and smaller than any of Keating’s eight except his first. (The data begins in 1970, but as the size of government has grown steadily since Federation we can be confident all percentages before 1970 were smaller than these.)

These numbers don’t reflect the attitude of these gentlemen, or of their colleagues, to the size of government; they are a function of the conditions under which they laboured. Keating and Costello were treasurers when the economy was galloping and the coffers overflowing, which enabled generous hand-outs and handbacks, and much chest-beating about returning to surplus and dealing with the mess bequeathed by predecessors. And a good economy in itself also assists longevity.

And while Keating and Costello no doubt did good things, the chief reasons for the economic plenty were not their own actions, but the international economic climate and decisions taken by their predecessors.

Keating quit the position when he challenged Bob Hawke in 1991, after Australia had gone into recession. Costello, with his party, lost the 2007 election a year before the global financial crisis clobbered the planet. In both cases, budgets returned to deficit and businesses and wallets closed. Never mind that we were the only advanced economy not to go into recession after 2008–09. The fun times were over.

Despite a tendency in this country to wallow in imagined economic exceptionalism, the uninterrupted growth from the mid 1990s to 2007 wasn’t a peculiarly Australian phenomenon. When British prime minister Tony Blair retired in 2007 he could boast of having presided over not a single quarter of negative economic growth.

John Howard couldn’t quite make the same claim. But when he suggested in the 1980s that the times would suit him, he didn’t know how right he would be.

The times didn’t suit Swan or Hockey, and they aren’t suiting this treasurer. For a while last year, Morrison looked to be a serious challenger to Malcolm Turnbull as successor to Tony Abbott, but instead he got the booby prize. It will do his long-term leadership chances no favours.

Anyone who wonders why politics looks harder these days shouldn’t ignore what happened in 2008. Governing was a relative doddle before the global financial crisis. Despite a pointless online meme this week from Labor supporters declaring that this budget proves the Coalition is a big-taxing and big-spending government, the fact is that we are still suffering the aftermath of the GFC.

When an economy slows, spending inevitably increases and revenue goes down, and that’s why very few advanced countries are spending less and taxing more as a percentage of GDP than in 2007. Even in David Cameron’s austerity-inflicted Britain, general government expenditure remains higher today, as a percentage of GDP, than it was under Labour in 2007.

So Morrison has little to play with.

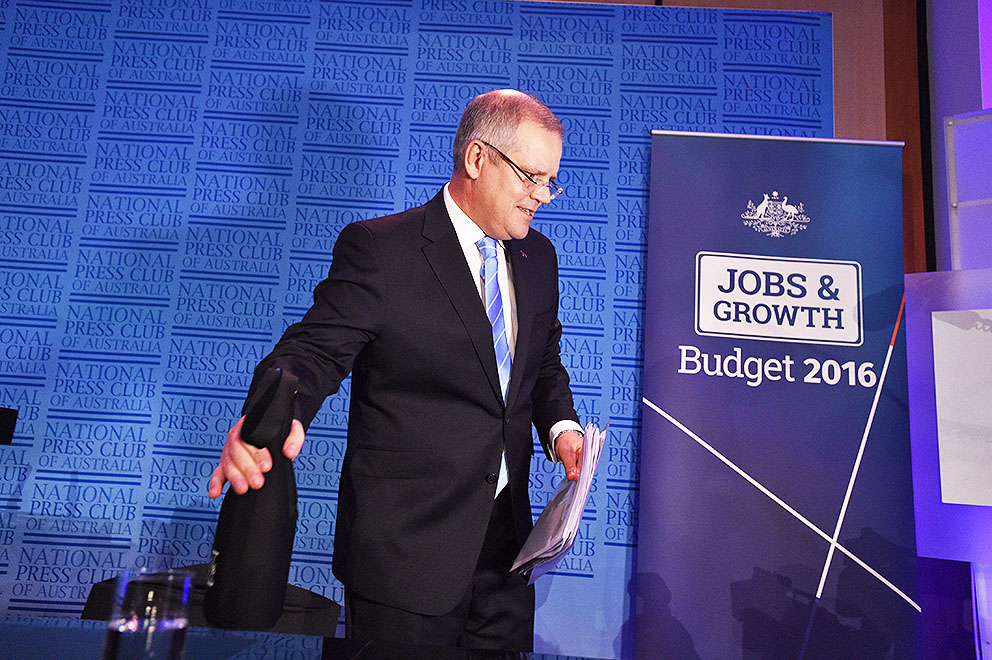

During his post-budget Press Club speech on Wednesday, perhaps the most assured answer from the nervous treasurer came in response to a question contrasting his 2008 maiden speech, which praised the Rudd government for increasing foreign aid, with yet another aid cut in the document he had just handed down.

“When I gave that speech,” he replied, “we had $40 billion in the bank and Labor blew it all. They blew it all, with reckless policies that set fire to the budget. It’s regrettable, it grieves me, I know it grieves Julie [Bishop] terribly. But don’t elect the government that’s going to set fire to the budget, then you won’t have to worry about that.”

If budgets matter much politically, it’s less the result of the goodies bestowed on key sections of the electorate and more because they are showcases of a government’s economic prowess. In the case of the current outfit, the best they can hope for is a perception not that they’re magnificent, but simply that they’re okay, and a hell of a lot better than the Labor Party.

Hence the continuing narrative: Rudd inherited surpluses from Howard; at least we’re taking the debts and deficits seriously; you can’t trust Labor with the budget.

As unfair as it is, it’s the most powerful tool in Turnbull and Morrison’s armoury, one that they’ll keep using right through to election day. •