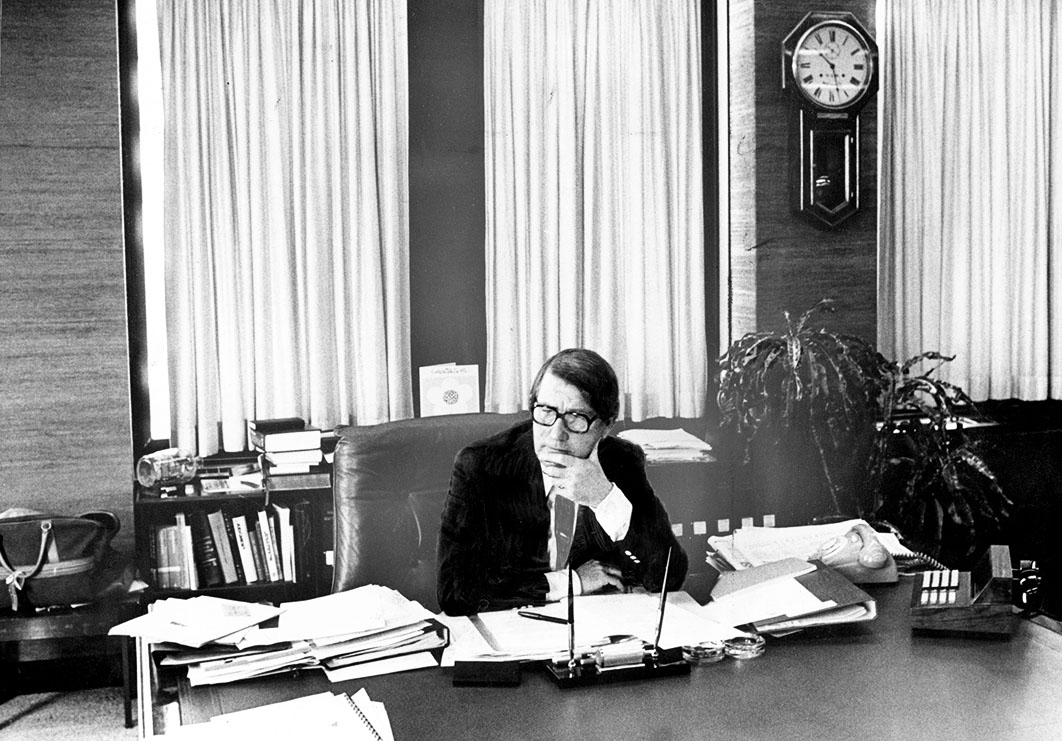

It isn’t surprising that Neville Wran enjoys an honoured place in Labor’s pantheon of modern heroes. When party supporters were in despair after the Whitlam government’s smashing defeat in 1975, Wran unexpectedly took government by one seat in New South Wales, ending eleven years of Coalition rule. His two “Wranslide” victories followed in 1978 and 1981, with a narrower win in 1984. Then, after ten years as premier, he resigned in 1986.

Wran towered over his contemporaries in intelligence and acumen, but his policy achievements, while not negligible, failed to match his electoral triumphs. “I didn’t set out to achieve much, actually,” he said when asked to nominate his main achievements. “My principal objective was to keep beating the Liberals, and I’ve had amazing success at doing that. That’s been my main triumph.”

The biggest cloud hanging over Wran’s legacy was his handling of a series of corruption allegations. As biographers Mike Steketee and Milton Cockburn conclude, “while Wran’s cynicism did him no harm in the early years of his premiership, it almost brought him undone over the corruption issue. Here the cynicism was deep-rooted and absolute: corruption was not an issue because it did not affect people’s lives, as did bread and butter issues.”

The leading historian of NSW politics, David Clune, agrees. “When confronted with evidence of widespread corruption, Wran made the serious error of trying to obfuscate and cover up,” he writes. “Rather than admitting that there was a real problem that needed to be urgently addressed, he over-confidently assumed his political and parliamentary skills would enable him to defuse the issue.”

Even future Labor premier Bob Carr took Wran’s handling of corruption as a negative exemplar: “I had seen Neville Wran’s premiership tainted and compromised on probity by three distinct errors. One, the elevation of a corrupt cop as assistant commissioner. Two, the extension of the term of a corrupt chief stipendiary magistrate, Murray Farquhar. Three, being too slow to shake out police corruption… Almost every week I was to watch him struggle to ward off allegations that his administration was tainted by a laxness towards corruption.”

Allegations of corruption in the Wran era have flared up intermittently in the decades since his retirement. Most recently, early this year, the ABC series Exposed: The Ghost Train Fire aired claims about Wran’s role in organised crime figure Abe Saffron’s successful bid to lease Luna Park after the 1979 fire that killed seven people. At around the same time, former chief magistrate Clarrie Briese published Corruption in High Places, a memoir drawing on his long and distinguished career in the NSW judiciary, and Wran is one of his main targets.

“Laxness towards corruption” is one thing, but the sheer number of controversies and allegations involving Wran has persuaded some people that he was corrupt. What does the evidence say?

The brand of corruption most commonly associated with politicians is the kickback — the bribe given in return for a favourable decision. Huge stakes often hang on how governments respond to development proposals or land rezoning applications, for instance, and a sympathetic politician on the inside can make a huge material difference.

Despite some gossip, neither during nor since Wran’s years as premier has any evidence emerged that he received bribes or sought other forms of personal enrichment. That’s not to say he was unaware of the patronage potential of government decisions — for political advantage, though, rather than personal gain. In particular, Wran treated media proprietors the way the Morrison government treats swinging electorates: as targets of inducements intended to attract support in return.

The most important example is his decision to grant the Lotto franchise to a consortium whose members included companies run by Rupert Murdoch and Kerry Packer. It was a highly controversial choice, and defied NSW Labor Party policy. Defenders of Wran have argued that the marketing skills of the Packer and Murdoch companies, by guaranteeing that Lotto was highly successful, ensured that more revenue flowed to the state than would otherwise have been the case. But it’s also true that the franchise gave those companies a reliable, government-guaranteed source of income.

Wran’s wish to maintain good relations with the major media companies led him to offer Fairfax the chance to participate in Lotto as well, but its board felt that entering into an enterprise with the government it professed to hold to account would not be proper. Packer and Murdoch didn’t feel so encumbered.

Wran also helped Packer in other ways. When the mogul was trying to establish World Series Cricket, Wran’s government overruled the Sydney Cricket Ground Trust to give him access to the ground, and helped finance the construction of the light towers that enabled play to take place in front of prime-time TV audiences. Without calling for competitive tenders, the government also extended his leases at the Smiggin Holes and Perisher Valley ski resorts until 2025.

These decisions have no hint of personal financial gain, but they do suggest that Wran was happy to use the government’s prerogatives to advance Labor’s interests, and that he wouldn’t be inhibited by procedural niceties.

Wran inherited a corrupt police force. During the eleven-year premiership of his predecessor, Robert Askin, writes organised crime expert Alfred McCoy, New South Wales “endured a period of political and police corruption unparalleled in its modern history.” Although figures on illicit activity can never be authoritative, McCoy estimated that the annual turnover from organised crime in Sydney totalled $2.2 billion in 1975, with income from various sources of gambling comprising the major share, and narcotics $59 million.

When Wran was elected in May 1976, the corrupt Fred Hanson was police commissioner and a member of the panel that would nominate Merv Wood as his successor. A majority of ministers preferred Brian Doyle, who had a reputation of fighting corruption, but Wran wanted Wood, and in the end his ministers complied.

Over the following few years, Wood proved himself less than enthusiastic in pursuing organised crime. In November 1977, when Wran responded to public clamour by ordering the shutting down of Sydney’s long-tolerated illegal casinos, Wood’s public response was that such an action would be “inhumane” because 300 employees would lose their jobs just before Christmas.

In parliament in April 1979, Liberal John Dowd asked Wran why a 1977 report on the organised crime figure George Freeman had not been acted on. Wran claimed he hadn’t seen any such report, and promised that if it existed, which he doubted, he would release it to the news media. To Wran’s intense embarrassment, Dowd then produced a copy of the report. Wood was not only failing to fight police corruption, but he had deeply embarrassed the government by not alerting Wran to its existence. Wran subsequently released part but not all of the report.

Soon after, Wran announced that an anonymous informant had compiled a dossier seeking to prove that an association existed between Wood and a major illegal casino operator. Wood resigned a week later, ostensibly on the grounds of avoiding embarrassment to the police service. Months later Wran announced that the investigation had found the allegations of corruption to be politically motivated, although he never released the report.

Wran’s support for Wood’s appointment as commissioner could simply be bad luck — a case of taking the easier course of following the committee’s recommendation — and didn’t necessarily indicate he was indifferent to police corruption. The government was riding high electorally at the time, and although Wood’s misdeeds intensified attention on corruption, they did little or no damage electorally.

What did eventually transform the politics of organised crime in New South Wales was the murder of Donald Mackay on 15 July 1977. Mackay, a pillar of the Griffith community, had been nominated as the Liberal candidate in the next state election. Griffith was at the centre of a large marijuana-growing industry directed by organised crime figure Robert Trimbole, and Mackay’s anti-drugs campaigning was seen as an increasing nuisance.

Three weeks after what was officially labelled Mackay’s “disappearance,” a royal commission into drug trafficking was set up under Justice Philip Woodward. A year later, Woodward revealed how farcically incompetent the police investigation had been. Abundant material evidence made clear that Mackay had not disappeared but had been the victim of a violent attack.

In his final report, Woodward concluded that Mackay had been killed by a mafia-style organisation that was growing marijuana in Griffith. Several of its key figures had mixed socially with local police; indeed, former police chief Hanson used to go duck shooting with Trimbole. On the night the report was released Trimbole threw a large party at his home and boasted that “the commission can’t touch me or charge me in any way.” The NSW police investigation into Mackay’s murder made no progress.

Some years later, though, a Victorian police investigation into other crimes revealed that Mackay had been killed by a hitman, hired on instructions from Trimbole, because of the problems he had been causing the criminals.

Mackay’s murder had occurred just over a year into the Wran government but re-emerged in its last year, 1986, after the hitman’s conviction in Victoria. After a group of Griffith citizens critical of the NSW police’s inept investigation pressed for an inquiry, a delegation from the town, including three of Mackay’s children, had a three-hour meeting with Wran. Afterwards, the leader of the group described the encounter as a calculated process of intimidation, including personal abuse by the premier.

Wran did announce a new inquiry. But he also said, “It’s about time people in this country stopped yap, yap, yap and went along and put up, and that applies to the people of Griffith.”

The inquiry, headed by Justice John Nagle, reported in December 1986. As well as directing scathing remarks at the police, Nagle also brought into clear public focus a letter written by a former minister in the Whitlam government, Riverina resident Al Grassby. In 1980, Grassby had tried to persuade some Labor MPs to read into Hansard a document he had written alleging that Mackay’s widow and son and their solicitor had conspired to murder Mackay. The letter was the basis of a front-page article in the Sydney Sun-Herald in August 1980.

Political insiders had long known of Grassby’s links to Griffith criminals. Astonishingly, Wran appointed him to a community relations position in February 1986. Gary Sturgess, an anti-corruption campaigner and chief of staff to opposition leader Nick Greiner, told the Sun-Herald he was “sickened” that “Wran would take on a man with such obvious links to the mafia.” During a strong attack in parliament Greiner argued for Grassby’s activities to be included within the scope of the Nagle inquiry, but the government made no response.

If Wran could plead bad luck in appointing the corrupt Merv Wood, his problems with another police officer, Bill Allen, were all of his own making. Apparently impressed by the way Allen cleaned up a tow-truck scandal, he twice promoted Allen over more senior officers and against opposition within the force. Thanks to this patronage, Allen became deputy commissioner in August 1981.

Allen’s brazen behaviour in the job suggested he felt untouchable. On numerous occasions he met with Abe Saffron at police headquarters. He and his family accepted free trips and hospitality in Macau and Las Vegas from illegal gambling interests. He tried to bribe a junior police officer with five payments amounting to $2500 in cash.

Allen’s career came to an abrupt end in 1982 after the release of a damning Police Tribunal report. Then, according to Steketee and Cockburn, the government made “what amounted to a deal with Allen.” In return for not contesting the charges, he was demoted to sergeant first class but allowed to retire and retain his pension. This, of course, meant that his conduct was never publicly explored.

The government had just secured a huge victory in the 1981 election, and was in a position of political strength. But the scandal produced the first instance of the extravagant, partisan invective that became more common in later years. When National Party Leader Leon Punch said that Allen was Wran’s bagman, Wran replied in spades: “Last week I called you a piece of slime. Now I call you a cur, a coward.” This unedifying spectacle covered the fact that no effort was being made to probe Allen’s actions and relationships.

Wran later complained that the Allen affair “was built up into a big issue,” and that Liberal prime minister Malcolm Fraser “went on a destruct and destroy course” against him, thus thwarting his hopes of moving into federal politics. This is baseless special pleading: a blatantly corrupt deputy commissioner would always have been a big issue, and it was commonplace for federal ministers to brief journalists about state developments.

When Clarrie Briese was appointed chief stipendiary magistrate in March 1979, his predecessor invited him to dinner. Briese later concluded that all four of his fellow diners — retiring chief magistrate Murray Farquhar, police commissioner Merv Wood, lawyer to organised crime Morgan Ryan, and High Court judge and former federal attorney-general Lionel Murphy — were corrupt.

Evidence of the corruption of Wood, Ryan and Farquhar manifested itself immediately. Farquhar’s last case involved drug charges against two men, Roy Cessna and Timothy Milner, represented by Ryan. Wood intervened by radically reducing the estimated value of the drugs seized by police, which allowed Farquhar to deal with the matter summarily — and more lightly — rather than referring it to a criminal trial. Before hearing the case Farquhar thoughtfully shifted to a courtroom with no sound-recording equipment — a move, writes Briese, that left the police prosecutor indignant and helpless.

Of all Farquhar’s suspect cases, this is the only one in which the corrupt motive seems to have been purely financial. Otherwise, his motive seems to have been primarily political or personal.

Farquhar’s judicial dexterity would first have impressed Wran while Labor was still in opposition. News Limited wanted to build a printery on land it owned in Botany, but the local council was planning to convert the area to residential use. Labor offered to intercede on behalf of News — rather zealously, it seems, for in 1975 charges were laid against the local state MP, Laurie Brereton, and Labor official Geoff Cahill for attempting to influence four Labor councillors. Brereton allegedly offered them money if they voted the right way and disendorsement if they didn’t.

Farquhar found the evidence against Cahill too weak and dismissed his charge. But while he found a prima facie case of bribery against Brereton, he deftly decided that the Local Government Act took precedence over the common law crime of bribery, and that under that act a charge had to be laid within six months, meaning it was now too late to proceed. Moves were made to revive the prosecution, but after Labor won the 1976 election the new attorney-general, Frank Walker, ruled on a technicality that the case could not proceed.

Brereton escaped a trial. It is a leap to then declare, as Wran’s former press secretary Brian Dale did, that the allegations were “tested and rejected in court.”

The magistrate’s next unorthodox intervention came after Wran had become premier. In a unique and vexatious private prosecution, Sydney solicitor Danny Sankey issued a summons against Gough Whitlam and his ministers Jim Cairns, Rex Connor and Lionel Murphy for conspiring to deceive the governor-general over the loans affair, which had created enormous controversy in the lead-up to Sir John Kerr’s dismissal of Whitlam. The case opened in the Queanbeyan Court on the Monday before the 1975 federal election and continued — despite having little or no legal merit — until early 1979.

In 1977 the case was being heard by magistrate Darcy Leo. A Labor MP had attacked Sankey and Leo in parliament, and Leo had sued the Sydney Morning Herald for defamation for its report. Farquhar visited him in Queanbeyan and convinced him to withdraw from the case. Farquhar took over, but Sankey appealed against the change and Leo was reinstated. So Farquhar’s intervention didn’t materially change things, though there was speculation that his aim was to help the Labor defendants.

Wran’s devotion to Farquhar was tested in March 1978, when the National Times reported that George Freeman had been ordered out of Randwick racecourse as a disreputable character, having entered as a guest of Farquhar. Farquhar argued that he had bought the ticket at the request of a doctor, Nick Paltos, and didn’t know it was for Freeman. (Paltos was later convicted and imprisoned for drug offences.)

Justice minister Ron Mulock didn’t want Farquhar to return to the bench until he had given a satisfactory account of his relationship with Freeman. Farquhar initially declined on the grounds that he was suing the newspaper for defamation. Wran thought this was a valid reason; Mulock did not. Wran called Mulock to his office, where he was confronted by half a dozen senior ministers. Mulock stood his ground. As he left, Wran said, “Well, you’re on your own now and it won’t be forgotten.” Eventually Farquhar resumed his duties.

A year earlier Farquhar had made another decision that was to become a much bigger media focus than any other corruption issue during Wran’s premiership.

On 30 April 1983, the ABC’s Four Corners reported that a charge of embezzlement against rugby league chief executive Kevin Humphreys had been dismissed because Farquhar, professing to be acting on Wran’s instructions, had pressured a magistrate to drop the case.

Wran immediately sued the ABC for defamation and used the prospective court case as a reason for not answering any questions. A week later the magistrate who dismissed Humphreys’s case, Kevin Jones, made a statement that Farquhar had told him that “the premier has contacted me. He wants Kevin Humphreys discharged.”

This confirmed the central premise of the program: that Farquhar had told other magistrates that the premier was on the phone and he wanted Humphreys discharged. Clearly the most important sources for the program were the magistrates who heard Farquhar say this. Attorney-general Paul Landa demanded Wran step down and call a royal commission, which Wran did. Landa, and perhaps some other ministers, appear to have thought that Wran was probably guilty.

After two months of public hearings attracting saturation media coverage, chief justice Sir Laurence Street concluded that Wran was not involved, and he resumed the office of premier. One telling piece of evidence in Wran’s favour was that his diary showed that at the time Farquhar said he was on the phone the premier was in a meeting with Treasury officials and his economic advisers.

Street also ruled that Farquhar had tried to pervert the course of justice and should stand trial. Farquhar was subsequently convicted and served time in prison. Humphreys had to stand trial again, was convicted, and had to pay a fine.

The exoneration of Wran has often led his supporters to be dismissive of the whole Four Corners report. Former Wran staffer Graham Freudenberg, for instance, asserted in his memoirs that “the Four Corners ‘re-enactment’ was based on a fabrication… The ABC swallowed it hook, line and sinker.” The reporter, Chris Masters, maintains that “in all important respects the program was correct.” It accurately reported that there had been a perversion of justice, and that Farquhar had invoked Wran’s name.

On the day of his acquittal Wran held a media conference targeting the ABC and its “blot on the history of so-called investigative reporting.” On four or five occasions journalists asked Wran questions relating to Farquhar and the fact that the chief magistrate had invoked the premier’s name. Each time Wran redirected the question to the sins of the ABC.

Wran had sat through testimony by several magistrates that Farquhar had used his name. He also heard testimony about the close relationship between George Freeman and Farquhar, which showed the magistrate had a very profitable betting relationship with the crime figure. (This also showed that Farquhar had lied to Wran and Mulock about his relationship with Freeman a few years earlier.)

Yet Wran refused to utter a word of criticism of Farquhar, and neither he nor Street showed any curiosity about Farquhar’s motives for his corrupt behaviour. Nor did Wran show any interest in what Farquhar’s behaviour revealed about the administration of justice in New South Wales. As Masters commented, all who knew the case — including much of the NSW magistracy — believed the premier was involved. That belief “was a cancer that had been eating away at the NSW judiciary for six years.”

Many observers have said that the royal commission brought an enduring change in Wran’s attitudes, permanently reducing his enthusiasm for the role of premier. It also signalled an enduring rise in the prominence of corruption issues in NSW politics.

While Wran was still standing down, federal sources informed his deputy, Jack Ferguson, and police chief, Cec Abbott, of evidence that the state’s prisons minister, Rex Jackson, was accepting bribes connected with an early-release scheme he had introduced. Half-hearted internal investigations followed.

After Nick Greiner aired the allegations of bribery, Ferguson announced an inquiry. Then, in October 1983, federal opposition leader Andrew Peacock made much more specific allegations. Finally, the Fairfax weekly, the National Times, obtained incriminating information from Federal Police phone taps and on the morning of 26 October put detailed questions to the premier’s and the prison minister’s offices. That afternoon Wran, back as premier, demanded Jackson’s resignation.

The government’s stonewalling had certainly not disposed of the Jackson issue, and the fact that it was constantly on the back foot possibly increased the damage. Jackson eventually became the first prisons minister in Australian history to go to prison. Wran knew nothing about his minister’s corruption, but the resulting scandal further heightened the tension around corruption issues.

Allegations of corruption were becoming more frequent. When the National Times reported that secret police tapes revealed the identity of a Mr Fix-it for organised criminals, the Wran government’s initial reaction was to “feign disinterest,” which — according to Steketee and Cockburn — had become its favourite strategy.

At the same time, two other new allegations of corruption were made: investigative journalist Bob Bottom said that a NSW magistrate had conspired with a criminal figure to have a charge dismissed; and deputy federal National Party leader Ian Sinclair said that figures connected with the NSW government had said charges against him could be dropped if he paid $50,000.

Sensing that both claims were false, Wran moved immediately. He set up a commission of inquiry under Justice Ronald Cross to examine these two charges as well as the Jackson bribes. Cross disposed of Bottom and Sinclair quickly and absolutely. “The Spanish Inquisition would not have convicted the devil himself” on the kind of evidence Sinclair had given, he declared.

During the Cross commission, Bottom handed over a thick file on NSW police phone taps. The reaction was swift, Steketee and Cockburn write: “Three days later, the government announced through the Sunday newspapers new laws making it an offence to knowingly be in possession of a transcript or other records… of a private conversation illegally heard or recorded by a listening device.” Facing a penalty of up to five years’ jail, Bottom took the tapes to Melbourne, which is why this essentially New South Wales story was first published in the Age.

The last big corruption scandal of the Wran era came to be known as the Age tapes. It began dramatically on 2 February 1984 with a front-page story titled “Network of Influence,” based on tapes and transcripts gathered illegally by NSW police officers. No doubt sensitive to the possibilities of a defamation suit, the Age didn’t mention any names, focusing on audio recordings of Mr Fix-it and his dealings with a judge. Later, under parliamentary privilege, the crime figure was revealed to be Morgan Ryan and the judge Lionel Murphy.

Even before the names emerged, Wran was condemning the publication using two main lines of attack. The first was to say the tapes were phoney. The second — not necessarily consistent with the first — was to declare that those responsible for the taping should be jailed given that it was “the most illicit, illegal and despicable affair in Australian history.” Wran focused entirely on the illegality of the taping and, beyond calling them fakes, showed no interest in the tapes’ contents.

On the basis of Wran’s statements, the officers in the Crime Intelligence Unit who had made the recordings decided to deny all involvement. Much of the equipment was destroyed, as were many tapes and transcripts. Eventually a royal commission under Justice Donald Stewart offered the police officers immunity from prosecution, and later decided the tapes were genuine but the officers’ summaries were not sufficiently reliable to be used in criminal proceedings. Wran’s interventions had caused not only a long delay but also the destruction of much potentially valuable evidence.

The phone tapping was not the rogue operation that Wran’s comments suggested. Its origins went back to 1967, when police commissioner Norm Allan was looking for more effective ways to attack organised crime. NSW police were impressed by the FBI’s techniques for targeting and tracking such suspects, and a series of police commissioners handed the system down to their successors.

Justice Stewart concluded that some convictions would never have occurred if the unlawful interceptions had not helped in the gathering of evidence. Journalist Evan Whitton offered two cases: the first, the arrest in January 1978 of Wood’s old sculling partner, Murray Stewart Riley, and his conviction, with nine others, for attempting to import drugs; the second, the arrests in Bangkok of Warren Fellows, Paul Hayward and William Sinclair on heroin charges in October 1978 based on information gained by a phone tap on notorious crime figure “Neddy” Smith. As Justice Athol Moffitt, who led the first royal commission into organised crime in 1973, wrote later, “It seems clear the illegality of the tapes was not complained of for some years until politically damaging contents were published in the Age.”

With the fallout from the Age tapes threatening to run for months, and with the respite offered by Justice Cross’s findings on the false allegations, Wran seized the political initiative and called an early election for March. Labor won, but with a much reduced majority. Afterwards Wran made the double-edged boast that if he had had the material Greiner had, he would have won easily, and that the opposition dropped the ball by taking its eye off corruption issues.

Justice Murphy’s figuring in the phone taps began a series of political and judicial processes to explore his behaviour. A Senate committee was convened in late March 1984 and reported in August, split along party lines. A four-person second committee was formed in September and split three ways, with the chair, Labor’s Michael Tate, and Australian Democrat senator Don Chipp concluding that on the balance of probabilities Murphy was guilty of misbehaviour sufficiently serious to warrant removal from the bench.

On the basis of testimony given to the Senate committees by Briese and by Justice Paul Flannery, the federal director of public prosecutions, Ian Temby, decided to lay charges against Murphy. The first trial began in June 1985, and in July the jury found Murphy guilty of one charge but not the other. In a second trial in April 1986, Murphy was found not guilty, but controversially chose to make an unsworn statement — a procedure introduced to protect the illiterate — that allowed him to avoid cross-examination. Murphy wanted to return to his position on the High Court, but several of his fellow judges resisted. A parliamentary inquiry into allegations of misbehaviour was closed down when Murphy was diagnosed with cancer, and his death in October brought a huge outpouring of sympathy.

With the election behind him, and with his friend Murphy squarely in legal and political sights, Wran’s rhetoric became increasingly reckless. After Briese testified at the second Senate committee, Wran said, “His evidence raises grave questions about him, his conduct and his future. Obviously a very large question must now be hanging over him and his position as chief magistrate.” After Murphy was found not guilty at the second trial, Wran said of Briese, “He hasn’t enjoyed my confidence for a while but all the less because of this verdict.” He also suggested Briese was having secret dealings with the Liberal Party.

Wran’s statements moved several figures to come to Briese’s defence. Federal Labor attorney-general Lionel Bowen said Briese had his confidence, and Sir Laurence Street and five other Supreme Court judges wrote to Wran saying there was not the slightest justification for any action against Briese. Temby decided Wran should be charged with contempt of court.

Despite his outraged rhetoric, it should be remembered that Wran does not figure directly in the police tapes and transcripts at all. Ryan is heard talking to Farquhar, to Murphy and to Saffron. Wran figures only as a shadowy presence whom others talk about. Indeed at one point, Ryan tells a friend that Wran is straight.

The only claim against Wran himself in this controversy was made by Senior Sergeant Paul Egge, who said he had seen a transcript of Wran saying he would help Abe Saffron get the Luna Park lease. There is no trace of this transcript anywhere, and Egge said it was destroyed by his supervisor because it was “too hot.” This is the only such reference I have seen to a transcript being destroyed because it was “too hot.”

In sum, the Age tapes provided no evidence of Wran engaging in any corrupt behaviour. But his violent rhetorical responses were central to how the public controversy developed, and undermined any hope of a rational and informed debate.

Corruption became a running sore in the last years of Wran’s premiership. The simplest explanation for why this happened is that Wran himself was corrupt. Some closely involved people decided this was the case: Briese says that he, investigative reporter Bob Bottom, and state Labor minister Barrie Unsworth all “came to suspect that Wran himself was part of the problem of corruption in NSW, and for that reason was not interested in a conclusion.”

But Briese produces no evidence. He relates how, when he became chief magistrate, Farquhar asked whether he would handle sensitive cases for the premier, and said that such requests would come through Morgan Ryan, but Briese later writes that no such cases ever came.

When we are trying to decide whether a political leader or a government is corrupt, we are faced by two opposite but equally important obstacles. One is the secrecy surrounding corrupt behaviour. The other is that false accusations and groundless rumours aren’t unusual, especially about successful politicians.

Despite gossip to the contrary, no persuasive evidence exists to support the view that Wran was corrupt in the sense of seeking personal financial gain. Nor is there persuasive evidence that Wran directly or indirectly sought to advance any criminal interests, or had any direct or indirect relationships with such criminals.

What is offered as evidence of Wran’s corruption can sometimes be laughable. Herald Sun journalist and co-author of Underbelly, Andrew Rule, recounts that a businessman who knew Wran saw Saffron waiting in a brasserie presumably to have lunch with someone, then saw Wran walk in, look around and walk out again.

The greatest question mark hanging over Wran’s behaviour was his loyalty to Murray Farquhar. Wran never offered a word of criticism, even though staying silent flew in the face of clear evidence, defied colleagues and risked a political price. Perhaps this was because they had had corrupt transactions. If so, there were very few of them (although that would not excuse them) and they would amount to a very tiny tip of a much larger iceberg of controversy.

Wran’s ten-year premiership was a period of transition. Before it came the entrenched, unchallengeable corruption of the Askin era. A decade after Wran’s departure, important reforms had been enacted, creating a politically independent director of public prosecutions, an Independent Commission Against Corruption, the very thorough Wood royal commission into police corruption, and reforms to the police force.

Characteristically, Wran vociferously criticised the establishment of ICAC and predicted an incrimination free-for-all. “Each one will feed the crocodile in the hope that if he feeds the crocodile enough, the crocodile will eat him last,” he said. “Under cover of fighting the evils of crime and corruption, we may discover we have forfeited the basic freedoms which distinguish the democratic system from a totalitarian state.” This is not only an inaccurate prediction of how ICAC developed, it also neatly overlooks that such bodies also protect citizens’ rights against the abuse of executive power.

Wran’s recalcitrance on corruption issues is best explained by his political strategies and inclinations. He played party politics harder than most. Justice Donald Stewart, in many ways an admirer, also thought “Wran was a good hater.” Wran played his politics so hard that he refused even to speak to Nick Greiner, except once at a public function in 1985 when he roundly abused him.

Wran’s political strategy was to control the public agenda. Corruption allegations were a threat to this aim, and so his first inclination was to contain their damage. But this meant that he consistently gave a higher priority to political expedience than to public accountability, and his responses more often hindered than helped any efforts to increase transparency and secure meaningful reforms.

Wran’s strategy was not simply an attempt at political pragmatism that failed. It resulted from a moral compass indifferent to the larger issues that corruption posed for the health of a democracy. •

Text edited on 6 September 2021 to reflect the fact that a tender was indeed called for the Lotto franchise.