In 2016, when the Labor Party almost drove the Turnbull government into minority status, Bill Shorten earned a second term as opposition leader.

From time to time since then, Liberal figures have publicly expressed regret that the party ran a “positive” campaign. It was certainly not as negative as it could have been, and not as negative as Australian government campaigns usually are. And because the opposition was generally considered to have little chance of winning, Shorten and his team were not overly challenged by the media either — and the same expectation made it difficult to persuade voters to stress themselves about what Labor might do in office.

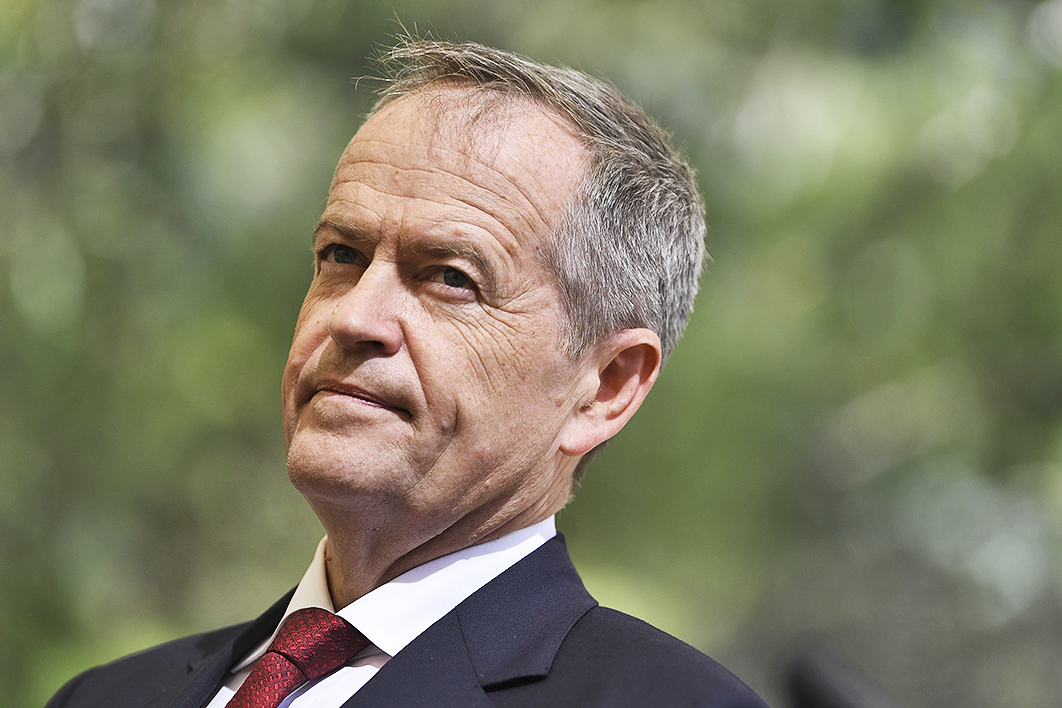

How different 2019 is, with Labor entering the campaign a very strong favourite, the government in ferocious attack mode, and Shorten finding himself under the kind of pressure that produces press conference stumbles. Earlier this week it was superannuation tax increases; most recently he delivered cringe-inducing avoidance of a question on climate change policy.

It’s horrendously difficult being a senior politician, even more so a leader, trying to survive interrogations without generating “gotcha” fodder for an impatient Twitter-submerged media.

But other recent leaders, on both sides, would have given more convincing answers, or non-answers, to the climate policy question. Shorten’s presentational shortcomings, forever evident, are coming to the fore: wooden, inarticulate, rehearsed and evasive. Even when the words he utters are perfectly reasonable, the delivery screams fake.

In 2010 it was revealed that opposition leader Tony Abbott had taken acting lessons, and no doubt many politicians have. It’s less about learning how to pretend than learning how to reveal more personality and be more “real.” Perhaps Shorten has tried and failed to address this problem, or maybe he never thought it mattered.

Labor’s approach, in both 2016 and 2019, also contains a contradiction. It is broadly running, in rhetoric and policy, a “left-wing” agenda, in keeping with the global post–global financial crisis “populist” zeitgeist, of soaking the rich, raising wages and increasing “fairness,” which has meant casting aside the traditional Labor obsession, in opposition, with being seen to be “economically responsible.”

At the same time — to make sure its costings actually add up — the opposition is putting forward two big policies, on housing and superannuation, to generate revenue and make savings. In inoculating itself from “where’s the money coming from?” it’s the most “responsible” opposition since, well, since… sorry to bring this up, John Hewson “lost the unlosable election” in 1993.

Maybe this tension reflects differences between Paul Keating fan Chris Bowen and Shorten’s whatever-it-takes attitude. But the sainted Bob Hawke and Keating rarely took big items to elections, usually springing them on voters mid term and getting them bedded down before the next election.

(Look at this Grattan Institute list of “reforms” over the past thirty-six years and count how many were actually given the tick by electors first. It’s a small minority.)

And with the scare-campaign potential much greater, taking big policies to an election from opposition is even harder than doing it from government.

(This time round, climate change is different. Given the political history, Labor needed to promise something serious, though maybe the reduction target is, in political terms, too big.)

There are four long weeks to go, and we haven’t really got to negative gearing and capital gains tax. They say being opposition leader is the hardest job in politics. This week Bill Shorten showed us just how hard. •