At 4.25 on the afternoon of 18 September 1926 a long whistle sounded and the SS Ryndam pulled away from the Holland America Line’s pier in Hoboken, New Jersey. The flags of thirty-five countries flew from bow to stern as the ship made its way down the Hudson River, UNIVERSITY WORLD CRUISE painted on its side. More than 1000 friends and family members stood on the shore, waving handkerchiefs and hats and blowing tearful kisses from the gangway.

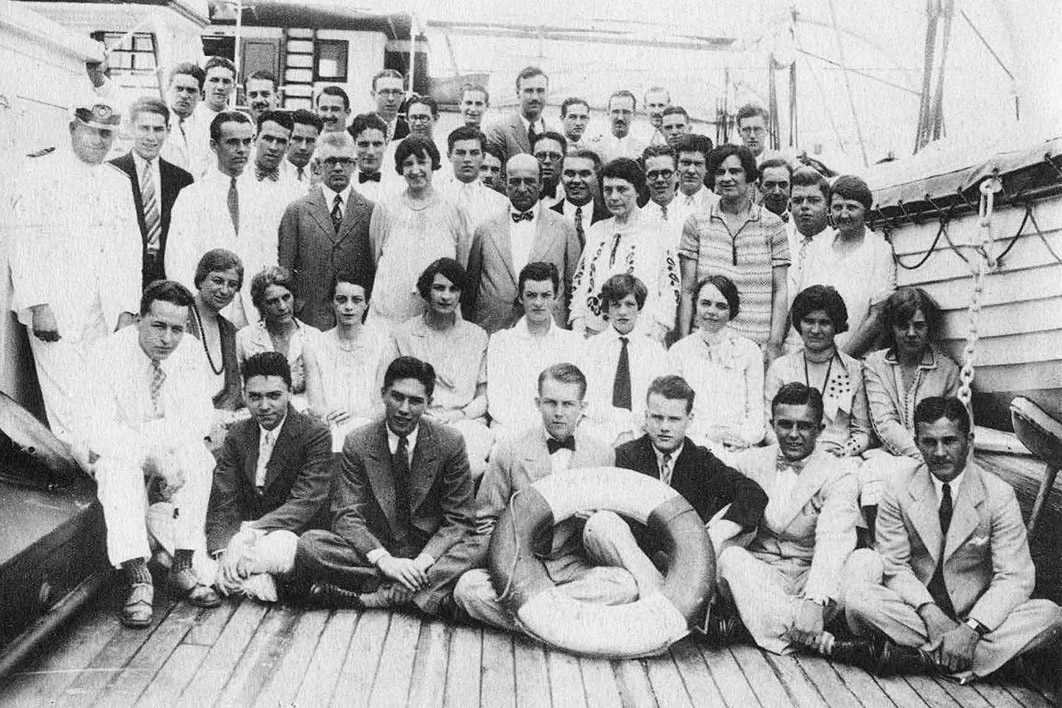

The crowd was there to bid farewell to more than 500 excited and slightly trepidatious passengers — 306 young men, fifty-seven young women, and 133 adults who were combining travel with education — and the sixty-three lecturers and staff who had signed up to join the Floating University: an around-the-world educational experiment in which travel abroad would count towards a university degree at home.

Over the next eight months they would meet some of the twentieth century’s major figures, including Benito Mussolini, King Rama VII of Thailand, Mahatma Gandhi and Pope Pius XI, and visit countries in the midst of change: Japan in the process of industrialisation, China on the cusp of revolution, the Philippines agitating against US rule, and Portugal in the aftermath of a coup.

In an era of internationalism and expanding American power, the leaders of this Floating University believed travel and study at sea would deliver an education in international affairs not available in the land-based classroom. It was through direct experience in and of the world rather than passive, indirect engagement via textbooks and lectures that they thought students could learn to be “world-minded.” The trip was promoted as an “experiment in democratic theories of education,” and New York University lent the venture its official sponsorship.

In championing the merits of direct, personal experience as a way to know the world, the Floating University was joining a set of public as well as scholarly debates taking place in 1920s United States about the relationship between professional expertise and democratic citizenship in increasingly complex industrial capitalist societies.

On the one hand, protagonists including secretary of state and future president Herbert Hoover and journalist and political commentator Walter Lippmann argued for the principles of scientific management and technocratic governance, and emphasised the importance of well-informed and expert elites. It was specialised knowledge, they believed, that was needed to address the challenges presented by rapidly changing economies and societies.

On the other hand, popular technologies such as photography, film, radio, inexpensive novels and newspapers, as well as cheaper transatlantic travel, jazz and the latest improvised forms of dance, seemed to offer direct, embodied and experiential ways of knowing that were at once deeply personal and widely accessible. Questioning the concentration of power in the hands of experts, labour, social and civil rights activists as well as populist and agrarian groups advocated for more participatory forms of democracy.

Although their differences are often exaggerated, the debates in the 1920s and 1930s between Lippmann and the educational reformer and philosopher John Dewey are often taken to be emblematic of this apparent opposition between technocratic expertise and democratic knowledge and deliberation.

Dewey’s thinking had a huge influence on the founder of the Floating University cruise, New York University’s professor of psychology, James E. Lough. Fascinated by education and the learning process, Dewey argued that knowledge does not flow from experience, but rather is made through experience; it was by doing things in and with the world that students would best learn. As a psychology student at Harvard in the 1890s, Lough was attracted to these ideas and, following his appointment as director of the Extramural Division at New York University, had a chance to put them into action.

Education at university — as at the primary levels of schooling — should be connected to the environment, experiences, and interests of students, Lough argued. From 1913 onwards his Extramural Division began offering credit-bearing courses at a variety of locations across New York City: onsite commercial, investment and finance courses on Wall Street, courses in government in the Municipal Building, art appreciation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and engineering courses at Grand Central Station.

Extending this logic, NYU also began offering summer travel courses to Europe to study economic conditions and industrial organisation in Britain and municipal planning in Germany. These courses resumed after the first world war and then — towards the end of 1923 — Lough took his ideas one step further. If summer travel courses could work, why not a whole year at sea? As he told the audience assembled at New York’s Waldorf Astoria hotel the night before the Floating University’s departure, those aboard the ship would experience “a method of study which actually brings the student into living contact with the world’s problems about to be realised.” The difference between it and what was ordinarily served up to students was, as he put it, the difference “between reading a menu and eating the full course meal.”

Putting this educational vision into practice, however, was harder than Professor Lough had anticipated. Despite some hiccups, the formal part of the undertaking was relatively successful. Students took formal classes while the ship was at sea. When it was stopped in port they participated in a variety of activities that included officially arranged shore excursions, visits to host universities and free time.

Although some professors were more diligent than others, the best among them linked their curriculum on the ship to the experiences students were having onshore. Undoubtedly a good number of students didn’t attend to their studies, but the official Report of Scholastic Work on the University Cruise around the World stated that during the cruise, 400 college-level students had attended classes (79 per cent of whom sought university credit). Their aggregated marks were mapped onto a bell curve: 16 per cent of grades were As; 38 per cent Bs; 28 per cent Cs; 9 per cent Ds; 3 per cent incomplete; and 3 per cent fails. Those who were “negligent in their work on board” were, concluded the Floating University’s academic dean, George Howes, no doubt also negligent in their college studies onshore.

It was the behaviour of the students in port that proved the biggest problem. Reports of sex, alcohol and jazz made their way back to an American press hungry for scandal, and the Floating University became a byword for what could go wrong with educational travel. “Sea Collegians Startle Japan with Rum Orgy” read one newspaper headline. “More than a hundred students, among whom six girls were to be noticed, were doing intensive laboratory work this evening, in the bar of the Imperial Hotel” continued the article.

And there were plenty of unfavourable stories to follow: more trouble with alcohol, rumours of romantic relationships and sexual relations between the students, accounts of a split between the cruise leaders, and even reports of an outbreak of bubonic plague. These accounts proved such catnip to American editors that it is hard to read the newspapers of 1926 and 1927 and not come across the story.

It didn’t matter to the newspapers that unruly student behaviour was a common aspect of life on college campuses across the United States in the 1920s. “There was a certain amount of necking on board,” was how one of the students, George T. McClure, put it, “but not more than I saw at the University of Colorado last year.” Playing on the popular image of the frolicsome college student — the smoking by women, the drinking by men, and the sexual promiscuity of both — was a guaranteed way to sell papers. But not far beneath such discussions of the misconduct of American youth lurked a fear that ungoverned youthful bodies might threaten the foundations of civility at home, while also betraying a lack of national readiness for the new global role the United States was rapidly assuming abroad.

By the end of the 1920s, huge numbers of Americans were travelling abroad. Many of them were students taking advantage of new and cheap “tourist class” transatlantic fares. And while they were away, many enrolled in one of the “educational courses” frequently offered by the shipping companies. During their voyages these travellers were undoubtedly learning something about international affairs and spending huge amounts of money in the process.

In fact, a report of the time suggests that in 1930 more than 127,800 Americans travelled “tourist class” to Europe: that is 5000 more people than were awarded a BA degree in the United States that same year. This was big business. With the Floating University and his other summer travel courses, Professor Lough had recognised the potential of this market for what was already beginning to be called “international education.”

But on the whole American universities wanted to have nothing to do with it. Although the trend had begun earlier, the 1920s was the decade in which they really marked out the boundaries of their empire of expertise. With newly established schools in a whole range of fields — from business administration and retailing to journalism and education — they asserted their claim to authority over both how knowledge could be acquired and whose knowledge claims should be trusted.

Rather than crediting educational travel programs, universities set about establishing what the League of Nations’ International Institute of Intellectual Co-operation called the “scientific study of international relations.” While for graduates and academic scholars who were undertaking research this might necessarily have entailed travel, for the much larger American undergraduate population it meant enrolling in credit-bearing courses and degree programs taught on home campuses, with syllabi, reading lists and assessments.

And for universities, it meant an entirely new discipline of teaching and study. It meant journals, conferences, summer institutes, government consultancies, and new paying audiences for university-sanctioned expertise.

None of this was compatible with educational travel of the kind Professor Lough envisaged. It was the university and its qualified faculty members that stood as the source of authoritative knowledge about the world, not the experiences of sundry travellers. In 1926 NYU pulled out of its sponsorship of the Floating University and over the course of the next few years abolished all its other study abroad programs. Although in 1930 the university did offer a course called Literary Tour of Great Britain, it took place entirely in a classroom in Washington Square, with readings supplied. In this 1920s contest between different ways of knowing the world, it was academically authorised expertise that triumphed, and it has undergirded the claims of universities — in Australia as in the United States — ever since.

Why does this matter?

For the last century or more, universities have derived their social standing (not to mention their income) from their claim to have authority over knowledge. They are the institutions that undertake the research, distil the learning, and provide the training so crucial to our economies and societies — or so the generally accepted story runs. Within their walls students learn from experts about the world and each other, developing both general and specialised disciplinary knowledge that prepares them not only for careers but also to be active and informed members of society.

But as anyone paying even a little bit of attention to politics and current affairs over the last decade will be aware, the university’s authority over knowledge is by no means uncontested. On the one hand, a new politics has emerged that challenges experts and their long-privileged authority, and instead prioritises personal, embodied and experiential ways of knowing. On the other hand, the proliferation of highly granulated, linked and disembodied big data, and the artificial intelligence algorithms that process it threaten to make obsolete many of the tasks that experts and knowledge workers have traditionally undertaken. Who gets to know in this new world?

There are many ways of warranting or justifying knowledge claims. In 1926 Professor Lough argued for the legitimacy of personal experience, but doing so brought him into conflict with the universities’ assertion of the authority of academic experts and “book knowledge.” But there are also other warrants for knowledge — authority, testimony, culture, tradition, or even divine revelation; all these can be invoked to support a claim to truth, and frequently they come into conflict with each other. Thinking about these conflicts can tell us a lot about how power and knowledge work in a society, especially in moments of change.

In their book Leviathan and the Air-pump, science historians Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer examine one such moment of conflict: the historical controversy surrounding the experimental demonstrations of the vacuum pump conducted by Robert Boyle and his assistant Robert Hooke in the seventeenth century. Boyle’s approach, which emphasised systematic observation, measurement and repeatability, represented a new way of producing knowledge that conflicted with Thomas Hobbes’s emphasis on deductive reasoning and mathematical principles. But crucially, as Shapin and Schaffer show, Boyle’s effort to establish the credibility of this new, scientific form of knowledge relied heavily on the social status and reputation of those men who were performing experiments and observing them.

We might think today that scientific experiment and academic expertise are self-evident means of arriving at the truth. But as various people (from feminist, Black and anti-colonial thinkers to Trump supporters) have pointed out, they are underwritten by social conventions and forms of power. Or, to put it another way, the social recognition Robert Boyle was able to mobilise was something Professor Lough failed to muster.

Too often, expertise is cast as a neutral or natural phenomenon, but expertise also has a history, one that is intimately connected to shifts in the nature and mode of power and rule. Thinking about why the Floating University was deemed a failure in the 1920s matters because it highlights the failure in our own times to ground knowledge claims in ways that are recognisable to those outside the community of academically authorised experts.

Experience and academic learning may now not seem so far apart. Internships, service learning, study abroad programs, field studies, work-integrated and simulation-based learning, collaborative research, and capstone projects are all part of the way most universities today deliver their degrees. In the United States, the Semester at Sea program, which claims the 1926 voyage as its progenitor, even allows students to credit time at sea towards their college degree.

But these initiatives don’t really settle the questions the story of the Floating University’s 1926 world cruise ultimately provoke: Who gets to know in our society? What forms of status determine what knowledge counts as legitimate?

These are pressing questions for democracies seeking to navigate change, and they are as relevant for twenty-first-century Australia as they were for Lough and Dewey and Lippmann in the 1920s and 30s United States. •