EVERY year tens of millions of rural migrant workers go back to their hometowns to celebrate the Lunar New Year Festival, or Chinese New Year, China’s most important annual event. And while this is a time of celebration for these millions of people, for the Chinese authorities it’s an anxious and logistically fraught few weeks. This year, shortages of seats on trains and buses and a further increase in the number of travellers have coincided with bitterly cold weather that has closed roads and disrupted train lines.

Although the day itself fell on 3 February this year, the epic movement of people began almost a month ago. Everybody was trying to avoid the peak travelling season, which began on 19 January. And while migrant workers constituted a considerable chunk of travellers, just about anyone in China who had left home for one reason or another was trying to make it to a long-awaited family reunion.

Urban workers from the most affluent cities in the east and south of China, for instance, were bound for their villages and towns in the underdeveloped central and northwest of the country. Shenzhen, in Guangdong province, is one of the departure cities, and it is from there that Wen Yu, one of the migrant workers, set out for home. An employee in a Hong Kong garment factory in Shenzhen, by the time I met her Yu had been queuing for more than ten hours next to a ticket window at the railway station in Guangzhou, Guangdong’s capital.

Yu is a short, slim twenty-seven-year-old worker who had made the two-hour trip from Shenzhen to Guangzhou a week earlier. Each day since then, she had dutifully headed to the ticket window at Guangzhou Railway Station, and eventually her persistence paid off. Having bought her ticket she could now embark on the 2000 kilometre journey to Chengdu, in Sichuan province. It would take about thirty hours to get there.

Amid the chaos at Guangzhou Railway Station, every available space to sit, rest or wait was priceless. By one estimate, twelve million people – a figure impossible to confirm – joined the exodus from here.

“I have been waiting to go and see my parents since last Chinese New Year,” Yu told me while she kept a close eye on her belongings and the time. She couldn’t afford to miss the 9 am K192 Guangzhou–Chengdu train. And, she added, “I also want to see my three-year-old daughter.” Yu’s daughter is just one among the estimated one million children left behind with relatives by rural migrant workers, and is being looked after by her parents. Yu will spend nearly three weeks at home before heading back to Shenzhen.

Yu works a twelve-hour day. She left the southwest province of Sichuan two years ago to work in Shenzhen, a promised land for migrant workers where dreams don’t always come true. “I send money home, I keep some for me and save to go home for the next family reunion,” she said. She makes around A$15 a day. “It was a good year.”

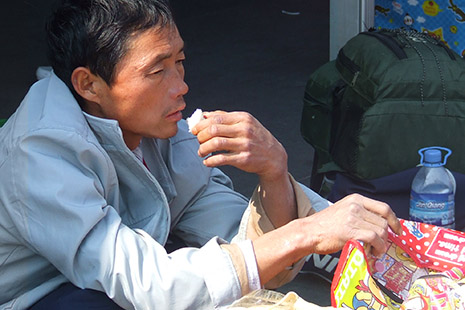

She has paid nearly A$30 in a cheaper “hard seat” carriage. She would have preferred to pay less, but this was one of the last few tickets to Sichuan. Thousands of others were left waiting, sitting on the dirty floor of Guangzhou Railway Station while a searing Chinese rap song served as a soundtrack. From time to time, a sudden frenzy would break out. Somebody, somewhere, had heard more seats had been made available. The stampede to the ticket windows left – for a brief moment – floor space for those who were just too tired to go. And then anger spread. Still there were not enough tickets available.

As 3 February approached, the desperate ones, those who couldn’t get train or coach tickets, had one more option: ticket scalpers. They are swindlers ripping off desperate souls. The Chinese government is aware of this and has promised ticket scalpers will be severely punished. The government says that 1800 ticket scalpers have been arrested and 14,000 tickets confiscated over the past two weeks.

But the crackdown on ticket scalpers doesn’t seem to have reached Guangzhou Railway Station – or not when I was there. My translator was approached five times by scalpers offering tickets for more than triple the normal price. The transactions were carried out openly and the police contingent at the station seemed more concerned about harassing a bunch of migrant workers who had become a little rowdy.

Last year’s official statistics indicated that the 200 million migrant workers are mainly farmers turned low-paid, unskilled urban workers. These people are the driving force behind China’s economic rise.

The Pearl River Delta area – where Shenzhen, Guangzhou and Zhuhai are located – is the magnet for about half of this army of migrant workers. They come principally from central China’s Hunan province, from northwest Sichuan province and from the southern provinces of Jiangxi and Guangxi, adjacent to Guangdong. They end up in the sweatshops or factories set up by businesses based overseas or in neighbouring Hong Kong. They often work overtime with low pay and inadequate safety protection. Their pay, although rising steadily in recent years, still lags behind the national average.

In Shenzhen, where migrant workers are paid better than most, the average pay is still less than A$15 a day. They live in overcrowded accommodation with no public facilities. For those migrant workers who have brought along their families, education for their children is non-existent.

THE annual journey back home for migrant workers has become a major test of China’s transportation system. It is estimated that each day during this year’s festival 6.2 million passengers were on the move – an increase of more than 10 per cent over last year. As Wang Yongpin, spokesperson from the Chinese Railway Ministry, told Xinhua news agency, “The volume of passengers increases each year, but this year we are expecting 230 million people.”

To cope with this demand, Guangdong’s authorities added more trains and buses. During the peak season, 9000 buses departed each day; meanwhile, according to the local railway ministry, more than four million passengers left daily on trains. Nearly 600 trains were added to the system and, in order to aid the flow of passenger trains, the freight rail system had been cleared.

Modernisation of the train system has become a priority for the Chinese government. Over the past five years, China has dramatically upgraded its vast rail system. The government has allocated 50 per cent of its A$53 billion infrastructure budget to building high-speed railways. It has laid down a remarkable 15,000 kilometres of new rail lines and introduced some of the most sophisticated high-speed trains. According to official figures, 1200 high-speed trains are in operation with speeds reaching 300 kilometres per hour or more.

These very fast trains have become the symbols of China’s modernisation. But according to a China Daily newspaper story published last month “the opening of more fast train services has led to fewer regular trains being available for budget-conscious passengers.” Indeed, few of the migrant workers will be travelling on these state-of-the-art trains because they can’t afford the A$50 tickets – equivalent to a month’s earnings in some cases. And most of the migrant workers come from provincial villages, places that fast trains don’t pass or won’t stop. Slow-train tickets cost less than A$30, so it’s not surprising that migrant workers keep opting for the old, overcrowded and poorly heated green trains.

Adding to the problems has been the weather. China has experienced one of its worst winters in thirty years. This has been especially the case in the southwest part of the country, the main source of migrant workers. The severe winter snow – up to twenty centimetres in some parts – has covered some of the key roads and railways heading to provinces such as Chongqing, Guizhou, Guangxi and Hunan.

None of this is good news for the government. Delaying journeys or closing roads means disrupting the flow of people eager to get back home. This becomes a political test, something that the Chinese government takes very seriously.

If something goes wrong, it presents a rare challenge to the Chinese Communist Party. For officials any major problem with the flow of travellers might end their careers. “A massive failure of the transport system will become a political issue and heads will roll,” says Judith Clarke, a Hong Kong–based academic.

The last major debacle came in 2008 when a snowstorm before the New Year Festival caused significant disruption. Many roads were closed and trains could not run. Some migrant workers lost their lives in the ensuing chaos. The Chinese premier, Wen Jiabao, had to intervene to impose order and mobilise the army to help sort out the mess. No senior politicians lost their jobs, but some heads lower down the hierarchy had to roll.

The Chinese government is determined it won’t happen again. A couple of weeks ago the Public Security Bureau in Beijing held a press conference to announce that road closures had to be better coordinated and no local officials could close a road without seeking approval from above. “We gained a lot of experience and learned lessons from the disaster relief work in 2008, with one of the important rules being not to seal off highways unless there is no other choice,” Feng Wilin, the Director of the Hunan Highway Administration, told Xinhua news agency.

Three weeks ago more than 70,ooo people had to be evacuated in Hunan because of the weather. In Guangxi 132 roads were closed because of the snow and icy conditions. The heavy snow also affected airports. Nearly 530 flights in the airports of Shanghai and Hongqiao were delayed.

The long-awaited Lunar New Year Festival is in full swing. And while millions of migrant workers – and others – have been looking forward to this annual family gathering, the Chinese government is no doubt looking forward to 27 February, when all of this will finally be over. •