In his infamous address to a conservative religious gathering last November, Joe Bullock reassured his audience that unions are a conservative force helping save the Labor Party from domination by lesbians and other dubious inner-city types. (By the time the speech became public, Bullock was at the top of Labor’s WA Senate ticket and just such a person was his number two.) Other union heavies see it differently, characterising their organisational links with Labor as a guarantee of an enduring radicalism. The truth is more mundane: the Labor/union relationship guarantees a parliamentary career to some people of real ability, but also to many of moderate talent (and sometimes moderate integrity), on salaries they could never otherwise dream of.

Apart from anything else, Joe Bullock must have been living in a cave for the past few years. Since Barack Obama’s “guns and religion” gaffe, it’s widely accepted that there is no such thing as a private speech. In front of any kind of audience, politicians should only utter views they are happy to have exposed to the world at large. And it is always interesting to see union leaders like Bullock can still be praised (or praise themselves) for representing the “most lowly paid workers” – hardly a glowing testimony to their effectiveness as advocates.

But the real problem is revealed by the selective way in which Labor goes about saving the voters from undesirable candidates. Prior to the 2013 election, Geoff Lake was stripped of his preselection for the safe seat of Hotham, in Victoria. His offence? A youthful indiscretion amid the hurly-burly of local government, in which he directed some inappropriate (verbal) abuse at a wheelchair-bound adversary. By contrast, Bullock’s CV includes an actual conviction, at a mature age, for (physical) assault. But in the deal-making context of his preselection, this was not seen as disqualifying him for a guaranteed six-year term in the federal upper house.

It is now suggested, in “seminal moment” terms, that the emergence of Bullock may serve to stimulate much-needed reform within the Labor Party, especially a reduction in the influence of affiliated unions and a corresponding empowerment of ordinary branch members.

In theory, it seems self-evidently a good thing for a political party to be as internally democratic as possible. For parties of the “left,” which historically pushed forward parliamentary democracy in the face of conservative opposition and obstruction, it seems at least credibility-enhancing if practices within their own ranks reflect principles they see as desirable for society as a whole. In this context, it might seem axiomatic that the union movement should not expect the same influence when it constitutes 17 per cent of the workforce as it did in the days when the figure stood at 70 per cent. But no quantitative fine-tuning seems to inform the outlook of those who support the current union dominance. That is their prerogative, of course, but we may take the view (to channel a recent prime minister) that we will not be lectured on matters of democracy by those who embrace the concept on such a selective basis.

When it comes to democracy and preselection, the problem is that branch members can make the wrong call just as often as union heavyweights or the party’s central office, especially when branches are so stacked that the process can’t be regarded as remotely democratic. In such a scenario, local preselection battles are likely to mirror broader factional power struggles, with no obvious benefit for party democracy. Those who regard an assault on branch-stacking as a necessary pre-condition for genuine party democracy would seem to be on the right track.

Nor is this problem restricted to Labor, as the preselection of detail-averse Liberal Jaymes Diaz in the federal seat of Greenway demonstrated in 2013. Unable to recall more than one point of a six-point policy, Diaz, who apparently secured endorsement through an ethnic stack of relevant branches, became something of a national media spectacle. The seat, which should have been a shoo-in for the Liberals, stayed with Labor. Had the central party apparatus overruled the locals, any vaguely suitable candidate would have almost certainly secured Greenway for Tony Abbott.

Even where no stacking exists, it doesn’t always follow that branch members will select the most suitable candidate with the greatest likelihood of winning the seat. This may not matter in safe electorates, but it can be important in marginal seats. Virtually by definition (leaving aside branch stacks), people who join a party are strongly committed to a certain worldview. The temptation to select those reflecting their own ideological rigidities, rather than more flexible types likely to appeal to the broader electorate, can be difficult to resist.

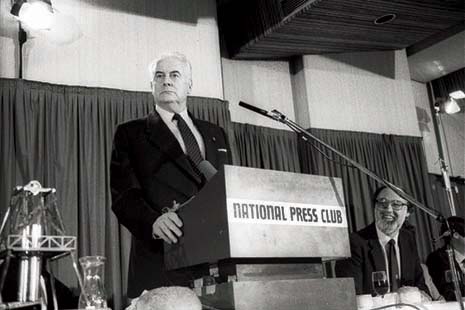

If Labor Party branch members had enjoyed the right to vote for the federal parliamentary leader in 1968, for example – as they do now – it is overwhelmingly likely that Jim Cairns would have beaten Gough Whitlam for the job (although Whitlam would probably not have brought on a contest against a figure more popular within the party in the first place).

To be fair, Labor has become such an ideology-free zone that the danger of selecting new-age dreamers or closet Marxists has long receded. Now, it’s the Liberals who are plagued by a form of this problem. Their frequent selection of extremists – one of whom compared homosexuality to bestiality – for unbeatable Senate positions warrants more attention than it has received to date.

A reality check should be inserted at this point. Federal Labor lost office in 2013 with essentially the same structure as it had when it won office in 2007. Parties that lose government nearly always undertake navel-gazing exercises about their structures, but there is no evidence that those whose votes decide elections are particularly fussed or even interested in such matters. It’s hardly the stuff of Monday morning chats at the water cooler.

There are two qualifications to this generalisation. First, any revelations of extensive union/criminal links uncovered by the current royal commission would be an electoral minus for Labor. But it needs to be remembered that right-wing ideologues persistently project their own anti-union views on the electorate. Notwithstanding the record low levels of unionisation in the workforce, polls usually indicate substantial appreciation of the overall role played by unions.

The second qualification concerns the link between structure and the candidates being selected. Given the shallow pool from which Labor selects, with the predominance of party and union officials and MPs’ staffers, there is the danger that the parliamentary membership is insufficiently representative of the society it seeks to govern. Whether this is a genuine electoral liability, or mostly just a useful throwaway line for Labor’s conservative opponents, is a moot point.

What a decent preselection process might be expected to elicit, among other things, is adequate information about the character of those seeking a parliamentary career. The present system has failed to do so, as evidenced by the examples of Craig Thomson, Peter Slipper and Bullock at federal level and assorted others at state level. When decisions are based on factional deals and branch stacks, this seems unavoidable.

With so many endorsements effectively predetermined on a factional basis, especially on the Labor side, is it any wonder that today’s MPs seem unpersuasive to the broader electorate, having had no need for such skills in securing their initial preselection? Crunching the numbers at a Chinese restaurant in Sussex Street is not quite the same thing as convincing an uncommitted voter of one’s fitness to govern.

In 1952, Gough Whitlam was seeking Labor endorsement for the seat of Werriwa. Local branch members played a critical role in a preselection that was a genuine contest rather than a factional fix. Direct, individual contact with these members was the only path to victory, which is how Gough found himself chopping wood and helping with other backyard chores while he attempted to persuade them of his superiority as a candidate. He succeeded well enough to take up a seat in federal parliament later that year.

How much wood did Bill Shorten chop for his preselection? •