I began to conceptualise my book, The Seventies: The Personal, The Political and the Making of Modern Australia, while I was immersed in the archives of the Royal Commission on Human Relationships at the National Archives of Australia. The royal commission emerged from the newly elected Whitlam government’s unsuccessful attempt in 1973 to liberalise the Australian Capital Territory’s abortion laws, which sparked a fierce parliamentary debate. While the debate — an all-male affair — couldn’t agree to change the law, it did produce a proposal for a royal commission into abortion. That attempt was also unsuccessful — I suspect neither side of politics wished to undertake it — but parliament did ultimately resolve to commission an inquiry into male–female relationships, which eventually, in 1974, became the Royal Commission on Human Relationships.

In the chair was Justice Elizabeth Evatt, who would become the first chief judge of the Family Court of Australia in 1975. She was joined on the commission by Anne Deveson, a trailblazing journalist with a passion for social justice, and Felix Arnot, the progressive Anglican archbishop of Brisbane. Their terms of reference were extremely broad: they had to examine the “family, social, educational, legal and sexual aspects of male and female relationships,” with a focus on sex education programs, medical training in sexuality, family planning, pressures on women in relation to children and family, and the legal and medical status of abortion.

The commission invited Australians to tell them “what do you think?” about sex, abortion, family life, family planning, parenthood, childcare, women’s rights and homosexuality.” People responded to this call in many ways. They gave evidence in person. They phoned in. They participated in research. They wrote official submissions that were available to be read while the commission was sitting. All of this material informed their final recommendations — more than 500 of them, published in five hefty volumes, that caused a sensation when they were finally released in 1977.

The submissions were as diverse as the people who wrote them. Whether they were typed on letterhead, or handwritten on floral stationery or in block letters on plain paper, they expressed a range of emotions: love, anger, loneliness, bewilderment, determination. People wrote with ideas for how to make human relationships better. They wrote to plead for political and social change or, sometimes, to prevent it.

When submissions arrived at the commission’s offices in Sydney, they were numbered and sorted into folders. The submissions on abortion offer a snapshot of the community’s polarised views. The push to liberalise abortion laws at the very beginning of the 1970s had inspired the formation of groups who challenged reform, such as Right to Life Australia. On the day parliament debated the abortion bill, women’s groups constructed a “women’s embassy” on the lawns of Parliament House, an appropriation of Indigenous protest strategies that dramatised women’s exclusion from the debate taking place inside the parliament. But they were outnumbered by their Right to Life opponents, who reportedly sent thousands of letters and telegrams to MPs urging them to reject any reform.

So it is unsurprising that many Australians wrote to the royal commission to oppose any liberalisation of abortion law on the grounds that it was a moral affront that would undermine the traditional family. These letter writers saw abortion as a “degrading” practice that lowered the “moral standard” of the family, and of society more broadly.

In contrast to this language of family, nation, and moral standards were other submissions, like this one from “Mary,” which was later included in Anne Deveson’s book about the royal commission, Australians At Risk:

Here is a personal testimony of what I had to go through to get an abortion in 1965. I was over forty three years old, but had a very young family; a girl under nine and a boy four. My loving partner was an alcoholic who made my life painful and unbearable, without hope or future.

Falling pregnant again, Mary had searched without success for a doctor who would terminate the pregnancy, her mental health deteriorating rapidly. When she finally obtained the abortion, she found that the doctor had also given her a hysterectomy without her consent. “I was given no explanation for this and no psychological follow up,” she wrote. “I hope no other woman has to live through a similar experience… [M]y nightmare of four months has given me the impetus to fight for abortion law appeal.”

In writing to the commission, Mary placed a deeply private memory on the public record to make a claim for abortion law reform. Other men and women wrote with similar intentions. Women who had experienced violent relationships narrated their experiences with uncaring police. Gay men and women wrote of the shame they felt concealing their sexuality. Mothers wrote about the difficulty of balancing family and work.

While the commission took testimony from doctors, social workers and other recognised experts, many of the people they heard from were ordinary citizens whose authority to speak derived from their private experiences. Many of these people were not only heard through their submissions, they also contributed to the commission’s public hearings, which attracted consistent media attention.

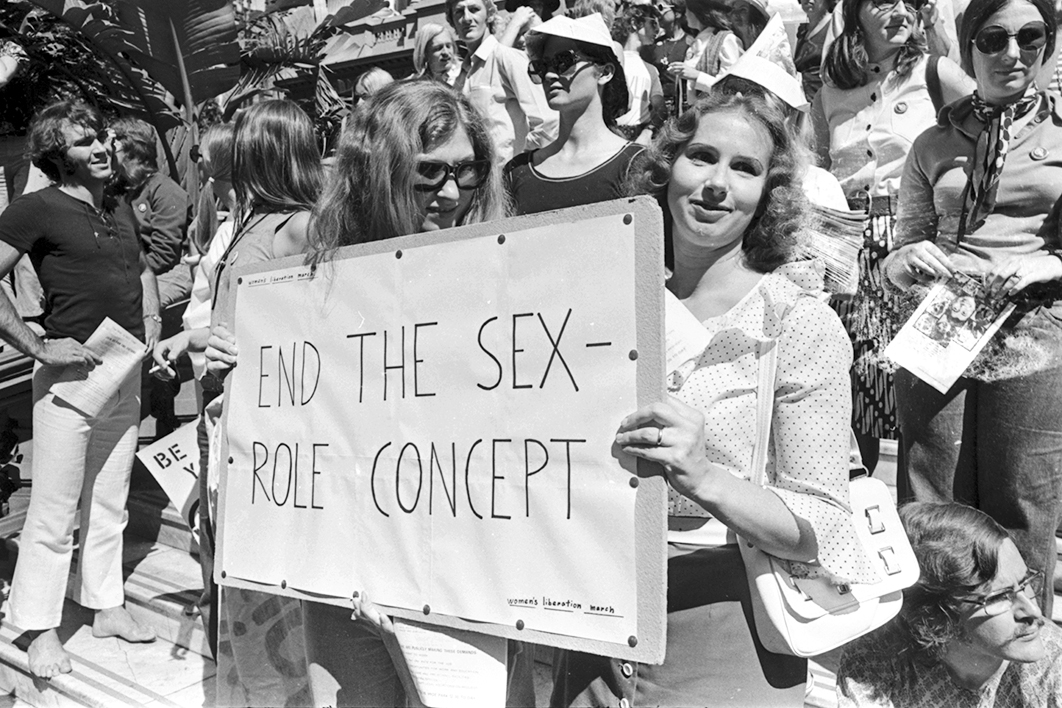

The commission enacted a kind of public intimacy similar to that which animated many of the social movements of the decade. It was a new way to talk about private life and about a new political strategy. It is best summed up by the women’s liberation slogan, “The personal is political,” an insight that emerged from “consciousness-raising,” the group discussions of personal life used to build political communities.

Women’s liberation and gay liberation were animated by this idea. The idea that the personal was political made Australians rethink the boundary between public and private. It changed our political and social life. All too often, though, this change has been obscured when we tell the national story of the 1970s.

We have long viewed the 1970s as a decade of political upheaval, centred on the drama of the dismissal of the Whitlam government on 11 November 1975. More recently, a second narrative of the 1970s has also taken hold. This story, told by Paul Kelly, George Megalogenis and other journalists, foregrounds the economic upheaval of the period — the stagflation, the end of the long postwar boom, the oil shocks — to frame the 1980s and 1990s as an era of crusading deregulatory reform.

Forged in the wake of the ground-breaking reforms of the Hawke–Keating governments a decade later, in the 1980s, this narrative reflects the centrality of economics in our framing of contemporary political life. Those reforms needed a genealogy, and portraying the 1970s as a decade of economic failure provided one.

I’m not suggesting that this story of the 1970s is inaccurate, or that the pain that the economic downturn caused was imaginary. But we construct historical narratives to serve our purposes in the present. This one was crafted to persuade us of the necessity — and success — of that later wave of economic reform. Today, as we tally the costs of deregulatory economic reform, we might write this history differently.

The economic narrative also obscures the extent to which the seventies was an extraordinary era of social reform and social contest. The decade saw the emergence (or reawakening) of many social justice movements. Many of our fundamental ideas about marriage and sex were challenged. Movements such as women’s and gay liberation reshaped our social norms and our political culture, even if their impact was partial and uneven. It was a turning point in the history of modern Australia, and fundamentally changed how we view private experiences and recognise the distinctive needs of women, children and people with different sexual orientations.

While none of these revolutions is complete, the struggles they animated reshaped Australia. But because we have tended to investigate these changes separately, rather than cumulatively, their collective impact has been more difficult to gauge. This relative neglect of the social transformations of the 1970s is even more striking when we think about the many ways that public discussion of issues previously considered private have shaped contemporary political and social debate.

Think of the recent explosion of stories using the hashtag #MeToo. The long campaign for marriage equality. The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. Domestic violence. Today, the politics of private experience takes up a lot of space in public life. Public discussion of these issues is characterised by an emphasis on personal testimony —individuals speaking publicly about private experiences.

Think of Chrissie and Anthony Foster, advocates for survivors of institutional child sexual abuse, or Rosie Batty, the 2015 Australian of the Year, who found a public voice as a woman who had endured domestic violence. The marriage equality campaign used ordinary people’s love stories to encourage Australians to vote “yes.” And #MeToo resonated so strongly because it gave women who had experienced sexual assault a platform for sharing personal stories.

It was in the 1970s that our ideas of what was “public” and what was “private” began to change. Women’s liberation and the gay and lesbian rights movement criticised the idea that things that happened in private were beyond the realm of politics.

“The personal is political,” the title of an essay by American feminist Carole Hanisch, was one of the most famous formulations of the Women’s Liberation Movement. It destabilised a foundational concept of modern political culture: the notion that there were two separate spheres of life, public and private. In this formulation, the public was the space of politics, government and paid work; the private was the place for intimacy and domesticity. The division between the two was strongly gendered, reinforced by ideology and government policy.

Citizenship is key to understanding these changing ideas of public and private. For much of the twentieth century, Australian citizenship was defined in exclusionary ways by ideas not only about race but also about gender. Historically, Australians’ rights to welfare, for example, were determined by gender as well as race. The foundational Harvester judgement of 1907 insisted that male wages should be determined by the needs of a male breadwinner with a wife and dependent children. This system — a form of social welfare – ensnared women as dependents of their husbands, as Marilyn Lake and other historians have demonstrated. In response, white women argued for special rights and protections (such as maternity allowances) on the grounds of their valuable national service as mothers, which further reinforced the gendered division between public and private spheres.

The assumption of male power within the family also left women and children vulnerable to abuse: domestic violence and rape in marriage, for example, were often viewed as “private” matters rather than crimes — indeed, rape within marriage was not criminalised nationally until 1991. And “privacy” was not an equal right: in some cases, it perpetuated oppression.

Across the 1970s, our ideas of what was “public” and what was “private” began to change. Second-wave feminism criticised the idea that what happened in private was beyond the realm of politics. As the split came into question, so too did the ideas of citizenship that had developed from it. Feminists no longer argued that motherhood was the basis of women’s contribution to the nation; gays and lesbians argued that keeping their sexuality “private” was oppressive and harmful.

Challenging and contesting the boundary between public and private life was central to the liberation movements of the 1970s. The changes they wrought in Australian social, cultural and political life are the subject of my book. It asks: how did the personal become political, and how did this change reshape the boundary between public and private life? How did this reshaping of what we thought of as public, and what we thought of as private, transform Australia in the late twentieth century?

These movements brought the personal to bear on the political in new ways. The shift rewrote our expectations of government and generated new ways to “do” politics and to become political. Women, in particular, emerged as a distinctive constituency with their own political demands: for women’s refuges, childcare centres, equal pay, and a host of other reforms. These new demands of government didn’t just change women’s lives — they changed our politics, the role of the state, and how we thought about citizenship.

They also created new kinds of political allegiance that didn’t always map neatly onto a male-dominated politics of left and right, Liberal and Labor. While Gough Whitlam appointed a women’s adviser to his staff, for example, many Labor MPs remained vehemently opposed to abortion. Later in the decade, prime minister Malcolm Fraser faced feminist opposition within his own party as he struggled to limit government spending on women’s services. The new politics of private experience carved new allegiances across long-standing political divides, and it continues to do so in often unpredictable ways.

These changes have not always been progressive. We can easily mistake decriminalisation of homosexuality or the Sex Discrimination Act as moves towards “equal rights” when in fact they didn’t guarantee these rights. The rights movements have been overwhelmingly white, though they have had vocal Indigenous critics (and sometimes participants).

The emergence of neoliberal economic prescriptions in the late 1970s also stymied and distorted many of the women’s movement’s key reforms. Childcare, demanded by mothers as a right to respite from the work of motherhood as much as a workplace entitlement, was soon tied to the goal of increasing women’s workplace participation and alleviating the “burden” women placed on the welfare system.

By the end of the 1970s, the ground had shifted beneath the feet of the liberation movements, and the logics of competition and deregulation had changed the framework of possibility for revolutionary gender and sexual politics.

To be interested in the 1970s, then, as the American scholar Victoria Hesford noted, “is to be interested in the alternatives offered to what has become our neoliberal present.” The seventies can provide us with a roadmap to understand the present day, but the era also gives us a glimpse of a different way of thinking about the nation, a way of imagining national belonging outside the framework of efficiency and productivity.

There are many ways to tell this story, but here I will focus on three case studies to show how these movements and campaigns reshaped Australian politics and conceptions of citizenship: early campaigns for homosexual law reform, feminist struggles to fund women’s refuges, and the emergence, in the late 1970s, of organised anti-feminist women’s groups. All reveal how the shifting line between private and public — between the personal and the political — reshaped both Australian politics and experiences of private life in the 1970s. Together, they show how the meanings — and the political uses of the private — changed over the period, with unpredictable consequences.

In the 1950s, according to the historian Graham Willett, homosexuality was “carefully excluded” from public life in Australia. Yet by the late 1960s, it had become an issue that many activists, civil libertarians and politicians believed needed to be “dealt with” through legislative reform. Why did this change take place? And how did homosexual people themselves emerge as part of these campaigns for decriminalization and equal rights?

Several factors were at play in the change, but perhaps most important was the gradual emergence in the 1960s of a liberal-minded middle class in Australia, members of which worked for reform in a number of areas, including civil liberties. On the question of homosexuality, they were guided by the Wolfenden report into sexual offences and prostitution, released in Britain in 1957. Wolfenden took as its guiding assumption the liberal view that homosexuality was determined by biology or childhood rather than “choice.” “It is not the function of the law to interfere in the private lives of citizens…” it declared. “[T]here must remain a realm of private morality and immorality which is not the law’s business.’

The report received surprisingly strong media and even religious support, but even with this backing, the British parliament was very slow to enact its recommendations, only passing the Sexual Offences Act in 1967. But that legislation came at an ideal time for Australians seeking similar reform here. The local call to decriminalize homosexual acts “between consenting adults in private” was, as Willett noted, lifted straight from the language of the Wolfenden report, and the earliest organisation to campaign for this change was not made up of gay men and women but of Canberra-based civil libertarians.

The Homosexual Law Reform Association of the ACT, formed in 1969, was one of the earliest organisations to campaign for homosexual law reform in Australia. Yet, as founder Thomas Mautner, a lecturer in philosophy at the ANU, stated, “we are not a society for homosexuals, and to my knowledge, no member of our committee is a practising homosexual.” The group argued for homosexual law reform on a platform of the right to privacy and protection of civil liberties: for homosexuality as a practice to be legal but publicly invisible.

When the pioneering gay rights organization CAMP — the Campaign Against Moral Persecution — was founded in 1970, only two of the founders were willing to be publicly identified in a newspaper profile in the Australian. Yet CAMP was different from the ACT reform group, because its members were themselves gays and lesbians. CAMP sought a new public visibility for homosexual people: in their first newsletter, Camp Ink, the group stated that: “the overall aim of CAMP INC is to bring about a situation where homosexuals can enjoy good jobs and security in those jobs, equal treatment under the law, and the right to serve our country without fear of exposure and contempt.”

By the early 1970s, gay activists were “coming out” rather than staying “private,” a brave move when male homosexual acts were still against the law. Being gay, then, was no longer simply a matter of what you did in private, but part of one’s intimate identity that could not be confined to the private sphere. The personal became political. Within just a few years, gay men and women were making submissions to government inquiries, including the Royal Commission on Human Relationships, and were seeking visibility, not privacy, to alleviate their oppression.

Women were also demanding new rights and protections from the Australian government. In 1973, Gough Whitlam was the first national leader in the world to appoint a dedicated women’s affairs advisor, the talented Elizabeth Reid. Reid worked within the government while activists worked outside it: both were equally important to the feminist reforms achieved during the Whitlam era.

The scale and scope of women’s activism in this period was immense, but I want to focus here on the development of women’s refuges, because they emerged from feminist theorising of the relationship between the private and the public, the personal and political.

While domestic and family violence has a very long history, it was reframed by the women’s movement in the early 1970s. The movement offered a new, structural analysis of domestic violence and a new response: the women’s refuge. Australia’s first women’s refuge was established in March 1974, when a group of Sydney women’s liberationists took possession of two houses in inner-city Glebe, establishing a refuge they named Elsie.

Feminist refuges like Elsie represented a new response to domestic violence: church-run women’s shelters had existed for decades but they focused on bringing families back together after violent incidents and offered no structural analysis of the problem of men’s violence against women and children. Women’s refuges were crucial to making the “private” problem of family violence visible in public: they drew attention to violence, but also to the lack of effective responses and protections for victims. Refuges sought to remove the protection of the private sphere — and its attendant shame — that allowed these crimes to continue, unprosecuted. Within a year of Elsie’s creation eleven women’s refuges had been established around Australia.

But even as women’s refuges quickly proved an indispensable response to the endemic problem of domestic violence, they remained a feminist innovation that sat uneasily within existing patterns of government service provision. Were they a health, housing, welfare or childcare service? Refuges served all these functions and more, but the integrated, overlapping nature of the work they performed made it difficult for them to secure government funding from a single agency or department. Even after refuges had some success in obtaining federal government funding, Australia’s system of federalism, where funding for health and other services is collected by the Commonwealth but administered by the states, produced significant funding inequalities across the country. Progressive state governments, like that of New South Wales, allocated considerable resources to women’s refuges, while others, like Queensland’s, did not.

Complicating the picture even further was the federal government’s shifting position on funding. Women’s refuges constantly had to pursue and defend state funding for their service in the face of threatened (and actual) funding cuts, and the Commonwealth ceased all dedicated federal funding for refuges in 1981–82. It would be more than a decade after the first refuge was founded before governments took any policy action on domestic violence beyond limited funding to refuges. Activists succeeded in politicising male violence against women in the 1970s, but securing stable government support for refuges would be an ongoing, and difficult struggle.

The struggle over refuge funding was a microcosm of the larger problem for the women’s movement. The mid 1970s was a moment of reckoning, with feminists facing a Liberal government that they feared would be less sympathetic to their demands for state support for women’s services. What they didn’t yet understand was that the mid 1970s was also the beginning of a seismic shift in western politics. The stagflation and recession of those years undermined the longstanding Keynesian consensus of the postwar period.

New economic prescriptions emerged, insisting that free markets, not state intervention, were the keys to greater efficiency, prosperity and freedom. By the early 1980s, a noisy faction of economic “dries” had emerged within the Liberal Party, emboldened by the economic downturn — and the lack of effective policy responses to it — that had overwhelmed Malcolm Fraser’s final term in office.

The feminist public servant Sara Dowse called this shift the “monetarist ascendancy.” Diverse groups including libertarians, devotees of the free market and moral conservatives all believed that policies and services designed to promote social equality were not only to blame for the poor economic conditions but also ran counter to conventional Liberal ideals of self-reliance and individual rights.

Shrinking the state would have particular implications for women, who had only just secured government funding for childcare, refuges and health centres. Reductions in these services would mean that women would once more be expected to shoulder the burden of family care and domestic labour. This dovetailed with conservative calls for women to renew their embrace of home and family. It was in this charged ideological space that anti-feminist women’s groups emerged and found a brief moment of political influence in Australia.

Two groups gained particular prominence: The Women’s Action Alliance, formed in 1975, and Women Who Want to Be Women, formed in 1979. While they were small, they exerted a measure of political influence: for example, Margaret Slattery, a member of the Women’s Action Alliance was appointed to Malcolm Fraser’s National Women’s Advisory Council in 1980, and members of these organisations were active in women’s groups in the Liberal Party. If we are to understand the impact of the women’s movement from the 1970s onwards, especially how it ruptured and remade the foundational categories of “public” and “private” and reshaped women’s citizenship identities, we must also consider the ways that this opened up possibilities for new kinds of anti-feminist activism for women.

Both Women’s Action Alliance and Women Who Want to Be Women were staunch and persistent in their advocacy for women they believed were neglected by feminism: stay-at-home wives and mothers. They sought to connect their activism to older traditions of maternalist politics while simultaneously presenting themselves as political outsiders, who had been displaced by upstart feminist activists. Depicting themselves in struggle against feminist “insiders” within government gave them greater credibility in their quest to gain influence over women’s policy in the late 1970s.

In their 1976 newsletter, Women’s Action Alliance argued that feminists lacked “expertise in the field of the woman at home” and had no “understanding or interest in the position of the full-time homemaker.” Women Who Want to Be Women constructed a constituency (in its newsletters) of “the silent majority of women, even those who haven’t heard of us, who want to be and are happy to be women.” The group objected vehemently to feminists in government roles and targeted their positions for abolition, and it made use of new channels designed to facilitate women’s access to government, like the National Women’s Advisory Council, to call for the abolition of these new forms of access.

Rather than embrace the women’s movement’s structural analysis of women’s oppression, anti-feminists asserted a liberal individualism in which state intervention was to be abhorred. Babette Francis, spokeswoman for Women Who Want to Be Women, told the Australian in 1980 that “promotion of theories of women’s oppression and disadvantage serve merely to destroy hope and initiative. Feminists, apparently, won’t feel their utopia has arrived until they have herded all women into one gigantic women’s refuge or rape crisis centre.”

At the same time, though, anti-feminist women campaigned for their own forms of state support using a politics of personal experience, just as feminists did. Anti-feminists called for new tax supports for single-income families and for financial assistance for women who chose to stay at home with their children. In effect, they used strategies developed by feminists to work against feminism’s goals. Their activism raises an important question: if the personal was political, then whose “personal” would be prioritised in Australian politics moving into the 1980s?

As we look back on the seventies today, it is clear that the feminist and sexual revolutions reorganised our public and private lives, with far-reaching and often unpredictable consequences. The faultlines in Australian politics have blurred and shifted; politics today is organised as much by gender and sexuality as it is by older ideas of left and right. Marriage equality, for example, was passed by the Australian parliament in December 2017 only after a postal survey demonstrated that there was majority public support for such a change. Just as abortion had fractured the 1973 federal parliament along cross-party faultlines, so too was support for marriage equality found across the political spectrum.

The Australian public’s enthusiastic endorsement of same-sex marriage in 2017 would have been unthinkable in the 1970s. The Royal Commission on Human Relationships, in a set of otherwise sympathetic recommendations on homosexuality, did not “feel able to” recognise homosexual marriages in 1977. Whether you think the passage of marriage equality legislation was radical or retrograde in 2017, that it happened at all was due to the persistence of activists, not politicians, and to a receptive public culture that offered LGBT people visibility and platforms to tell stories about their lives.

This is one of the important legacies of seventies movements: the creation of spaces for a range of perspectives in public life. Creating this space has helped to create social change. The Royal Commission on Human Relationships was one of the boldest enactments of the Whitlam government principle of “open government” and it gained its authenticity and authority from “ordinary” people’s stories of their experiences. Two more recent government inquiries — the Human Rights Commission’s Bringing Them Home report in 1997 and the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in 2017 — also demonstrated the powerful impact of telling personal stories in public.

These inquiries had limitations in producing change: Indigenous children are still removed from their parents at higher rates than the rest of the population, and the royal commission did not investigate the family and home, the place where most sexual abuse occurs. But they both helped shift public debate. In the words of Katie Wright and Shurlee Swain, the Royal Commission made child abuse “speakable and nameable” as a social problem.

Asserting that “the personal is political” was not enough to make change in the 1970s; it was a belief enacted through activism, and political reform. This reform was dependent on a strong activist presence beyond the parliament and bureaucracy. Elizabeth Reid could argue for change in government policy because there was a strong women’s movement supporting her; anti-feminist women, despite all their energy, failed to effect lasting change because they did not mobilise a large group of women behind them.

Women’s and gay and lesbian activists of the 1970s didn’t quite manage to remake the world, but perhaps it is unfair of us today to judge them for that, when we still have so much change to make. As Carol Hanisch reminded her readers in 1970, “there are no personal solutions at this time. There is only collective action for a collective solution.” Perhaps we need to reanimate this principle today, as we grapple with both the legacies and the unfinished business of the 1970s. •

This is the edited text of this year’s Ernest Scott lecture, presented on 19 September. The lecture can be viewed here.