Australia’s immigration department could once be numbered among Canberra’s feel-good portfolios. Federal ministers would be pictured spruiking the attractions of life in Australia around the globe, or smilingly welcoming newcomers to our shores, or shaking hands with the latest new arrival to have “made good.”

On both sides of politics — starting with the architect of the postwar immigration scheme, Labor’s Arthur Calwell (1945–49), and taking in a future Liberal prime minister, Harold Holt (1949–56), and a former champion cyclist, Hubert Opperman (1963–66) — it was essentially a good-news portfolio (although blemishes such as the controversial 1965 deportation of five-year-old Nancy Prasad to Fiji under the White Australia policy clouded the picture).

The Good Neighbour Council and other local organisations added to the positive mood, mobilising hundreds of community agencies and thousands of volunteers to help assimilate new settlers into Australian life. And once the White Australia policy had finally been buried in the 1970s, Labor’s colourful minister Al Grassby presided over a carnival of celebrated diversity, and the policy of multiculturalism was born.

But that’s all history now. With the rise of security concerns in the wake of the 2001 attacks in New York, immigration and its administration wear a sterner face. Ministers who once built their appeal on smiles and handshakes have been succeeded by hard men whose trademark is an unflinching political muscularity. The doormat marked “welcome” has been replaced by a “keep out” sign. It has done no harm to careers: two of the most recent incumbents faced off last week, with one almost becoming prime minister and the other one doing so.

In his first round of ministerial changes, prime minister Scott Morrison removed immigration from the direct responsibility in the home affairs portfolio of the man he defeated, Peter Dutton, who since 2014 had been Minister for Immigration and Border Protection as well as Minister for Home Affairs. Under Morrison’s watch (2013–14), the old Department of Immigration, Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship had been renamed the Department of Immigration and Border Protection; under Dutton, the quasi-military Australian Border Force had become part of the new Department of Home Affairs, and Dutton had also been given oversight of ASIO and the Australian Federal Police.

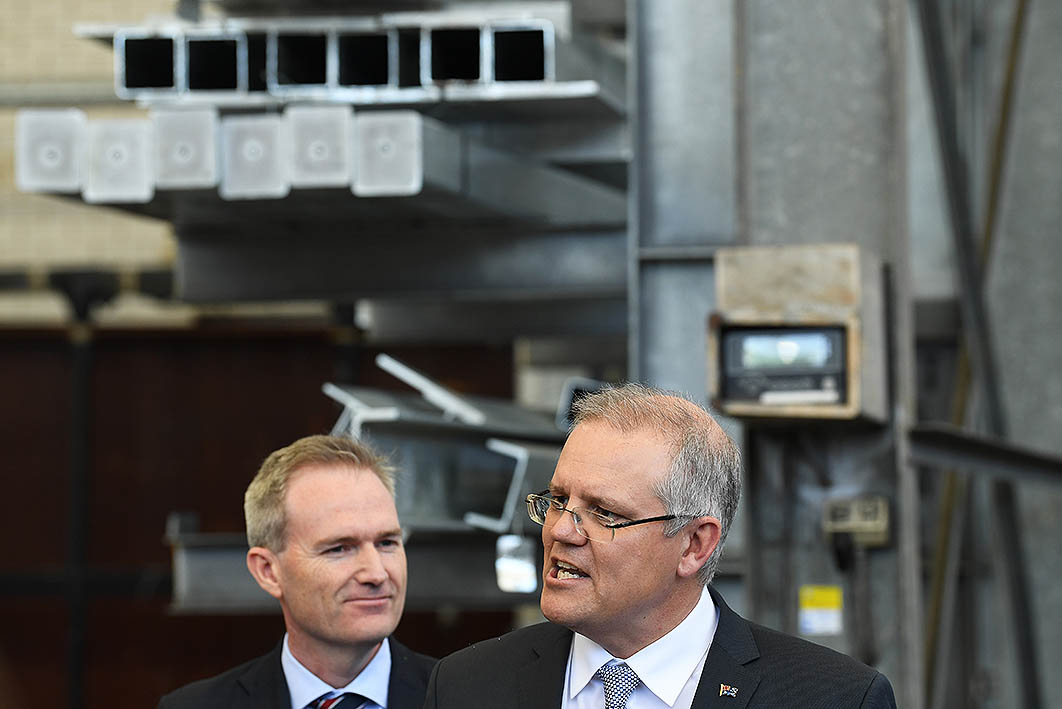

But Dutton had less than a year to enjoy his new powers. Among his changes to the portfolio, Morrison resurrected the old portfolio name, Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs, and appointed David Coleman to run it, though still under the Home Affairs umbrella. While a return to the sunnier pre-2001 style is unlikely, it’s clear that Coleman is no Dutton. As one fellow Liberal MP who has watched the Member for Banks closely since his election in 2013 commented, “He will put his own stamp on this; he is his own man and thinks for himself.” Not that he isn’t tough. Anyone who followed the parliamentary inquiry into the big four banks, which he chaired, would have witnessed interrogations of bank executives as relentless as they were incisive.

Although Coleman is regarded as a moderate within his party, the forty-four-year-old is neither a factional player nor a tribal Liberal. The youngest of six children in a non-conservative Catholic family, he joined the Liberal Party only in his late twenties, and went on to support marriage equality during last year’s debate.

Growing up in the lower middle-class Sydney suburb of Croydon Park, Coleman attended Catholic schools and went on to the University of New South Wales, graduating with an Arts–Law degree. His first full-time job was as president of the university’s politically unaligned student guild, from where he went on to the global management consulting firm McKinsey and Co., the springboard for many a political career, among them the former Liberal Party official and minister, the late Jim Carlton, current federal ministers Angus Taylor and Paul Fletcher, and rising Labor MP Clare O’Neal.

In the late 1990s, Coleman went to work for Australian search engine company LookSmart, a rising star among technology companies in the years before the dot-com crash, and then for the early online retailer dStore. In 2005 he joined Publishing and Broadcasting Ltd and the Nine Network, where he became the head of digital and strategy. Along the way, he sat on the board of Sky News and the financial advice company Yellow Brick Road. He made his first political foray, running against Labor premier Bob Carr in the state seat of Maroubra, in 2003. (Banks is his third attempt at a federal seat: he lost party preselection battles in Cook in 2007 and Bradfield in 2010.)

Perhaps unfashionably for a modern Liberal (not to mention a modern immigration minister), Coleman celebrates diversity and understands the pain of exclusion. As he noted in his inaugural speech to parliament, Australia has made its “national foundations stronger by allowing more people to build upon them.” He told how his grandfather could not get the job he wanted because he was Catholic, adding that “now we have Catholics in the most senior roles in the nation.”

He continued: “There was a time, of course, when Aborigines couldn’t vote, married women couldn’t work, and non-whites couldn’t immigrate. In recent decades we’ve made many important changes to our laws to give people the freedom to better build on our national foundations. We should never legislate for outcomes, but we should always be open to removing constraints that stop people from pursuing their dreams.”

Also unfashionably for a modern Liberal, Coleman raised a cheer for multiculturalism, noting proudly that his electorate of Banks had the highest proportion of people of Chinese background of any Australian electorate, and had among its residents people who traced their ancestry to all parts of the world. It was a picture that embodied modern Australia.

Coleman elaborated on his political journey, noting that he “wasn’t raised to vote for the Liberal Party, let alone join it, let alone represent it in parliament. I became a Liberal because my experience of life and my reading of history led me to a clear conclusion. Most of the time, when good things happen they happen because of the hard work of a small number of people. They don’t happen because a committee talked about them or because somebody published a discussion paper. They happen because people made them happen. Government should harness that creative energy by letting it be free.”

He also nailed his republican colours to the mast in that speech, observing that “the notion that our head of state should be determined based on who one’s parents are is, in my view, patently wrong.” Our faith in ourselves as Australians, he said, “should extend to an Australian head of state.” He added that his daughter, Caroline, “can aspire to be a great doctor, homemaker, police officer or teacher, but she cannot aspire to be the head of state.”

Testing times are ahead, especially as pressure mounts on the government from One Nation and others for an inquiry into population and immigration that has undoubted potential to severely damage the social fabric. These issues will require careful management, and it might be that the old feel-good days can’t return, but immigration under a thoughtful and reflective minister might not be seen in such a negative light as it has been in recent years. •