Not many countries give the right to choose their head of government to 172,000 predominantly elderly and affluent people comprising just 0.3 per cent of the national electorate. But the rules and membership of the British Conservative Party mean this is precisely how Britain’s new prime minister has been decided — and it is also why Liz Truss looks set to be Britain’s most right-wing leader since Margaret Thatcher.

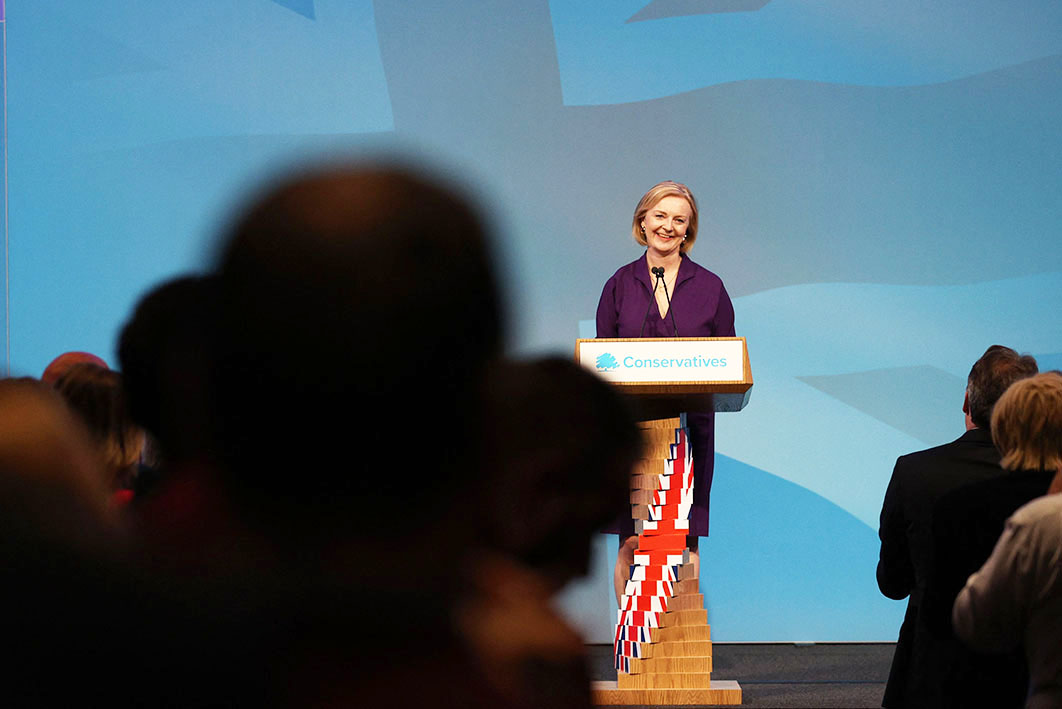

Truss’s decisive victory over her opponent Rishi Sunak, former chancellor of the exchequer, in the ballot of Tory Party members was by no means guaranteed at the beginning of the two-month leadership campaign. When Boris Johnson’s serial cronyism, misconduct and untruth-telling finally led to his ouster as Tory leader (and therefore prime minister) in early July, Sunak appeared his likely successor. He came out ahead in the initial series of votes among Tory MPs to identify the top two leadership candidates to be put to the wider membership. Truss was supported by less than a third of her own colleagues.

But over recent years the Conservative Party at large has changed. Once a broad church stretching from centrist “One Nation” Tories to ideological free marketeers, the party’s membership has narrowed since Brexit. With those who voted to leave the European Union in the 2016 referendum now dominant, many of its pro-European moderates have quit the party altogether. The desire to leave the EU was driven partly by anti-immigration sentiment and partly by a patriotic nostalgia for Britain’s free-trading past. But leaving was also seen as a means of liberating the economy from the alleged constraints of EU law and red tape.

Above all, for many in the party, Brexit’s purpose was to restore the small state, deregulatory agenda championed by Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s. Vigorously encouraged by the still highly influential newspapers the Daily Telegraph and Daily Mail, the party has consequently shifted decisively to the right. And Liz Truss understood this much better than Sunak.

Truss’s campaign emphasised her Thatcherite views from the outset. Her central message was that she would cut taxes: income tax, corporation tax and possibly even the value-added tax (Britain’s GST). Never mind the impact on public finances, with debt already at 100 per cent of GDP, post-Covid health spending rising sharply, and Truss herself promising to increase the defence budget following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Tory mythology remembers Margaret Thatcher as a great tax-cutter, and so Truss made this the centrepiece of her appeal to the party membership.

(Critics pointed out that Margaret Thatcher actually raised taxes in her first term of office to help reduce inflation, and only cut them when the public finances were in better shape. But this unwelcome fact failed to dent Truss’s appeal.)

For Truss — though for very few economists — cutting taxes and deregulating markets is the way to stimulate growth in the underperforming UK economy. Challenged about her proposed income tax cuts (via national insurance rates), which will give the richest ten per cent of the population an average benefit of £1800 (A$3050) a year and the poorest ten per cent less than £8, she described them as “fair,” arguing that growth was more important than distribution.

At the same time she has promised to scrap all Britain’s remaining EU-based laws by the end of 2023, including a swathe of employment, environmental and consumer protections. She proposes new low-tax and low-regulation “investment zones” to attract overseas finance. And, just in case this were not enough to ensure support among the Tory grassroots, she has promised to bring back selective grammar schools and scrap local house-building targets.

Liz Truss was not always a Thatcherite. Indeed, she was not originally a Tory at all. Born in 1975 to left-wing parents — her father was a professor of mathematics, her mother a nurse and teacher — Truss was an active Liberal Democrat as a student at Oxford. (One of the more entertaining features of the campaign has been footage of Truss at the Lib Dem national conference in 1994 proposing the abolition of the monarchy.) But two years later she joined the Conservatives, beginning her shift to the right.

After entering parliament in 2010, she founded the Free Enterprise Group of MPs, and co-wrote a right-wing manifesto entitled Britannia Unchained. Arguing for deregulation and lower taxes, the pamphlet notoriously described British workers as “among the worst idlers in the world.”

After a number of junior ministerial positions, Truss was appointed to David Cameron’s coalition cabinet as environment secretary in 2014. There, she became known primarily for a bizarre speech to the Conservative Party conference in which she criticised as “a disgrace” the fact that Britain imported two-thirds of its cheese. She campaigned for Remain in the 2016 EU referendum but changed her mind swiftly after the result, becoming a vociferous Brexit advocate.

As Boris Johnson’s international trade secretary Truss trumpeted her negotiation of a number of post-Brexit trade deals. Observers noted that most of these simply rolled over existing EU agreements. Her 2021 UK–Australia trade agreement, meanwhile, was widely criticised for giving Australian farmers greater access to the UK market without any reciprocal benefits for their British counterparts. Subsequently promoted to foreign secretary, Truss was frequently ridiculed in the media for carefully managed photo opportunities in which she appeared to be imitating Margaret Thatcher.

Truss’s performance as a minister didn’t commend her to many of her colleagues. As one put it recently, “her ambition is, undoubtedly, considerably greater than her ability.” Another branded her “as close to properly crackers as anybody I have met in parliament.” But her loyalty to Boris Johnson — backing him to the end, even as many of his cabinet (including Sunak) abandoned him — made up for that among party members, a majority of whom still don’t believe Johnson should have been deposed. And during the leadership campaign her ideological fervour won her the critical support of the party’s new right.

This is perhaps the most striking feature of Truss’s victory. Her campaign was backed both by supporters of Boris Johnson and by the party’s ideological vanguard. The latter are the same MPs who pursued the hardest form of Brexit and got rid of former prime minister Theresa May when she would not deliver it. During Covid they organised a libertarian resistance to lockdowns. Today their new target is climate change policy, which they see as a left-wing cause requiring excessive state intervention in the economy.

And they have already influenced Truss. Faced with Europe’s overdependence on Russian gas, which has seen its price skyrocket, Truss has come out not for more renewable energy but for a big expansion of domestic oil and gas drilling, including fracking. Leaving aside its impact on global warming, new oil and gas would take more than a decade to come onstream, far longer than an expansion of wind and solar power. For the party’s new right, though, climate change is a “culture war” issue that divides older Conservative voters from young metropolitan graduates, and being pro–fossil fuels is part of the strategy. Next in their sights is the repeal of Britain’s target of reaching net zero emissions by 2050.

Liz Truss therefore starts her term as prime minister with a well-prepared agenda. Her only problem is that very little of it bears any relationship to the crisis in which the country finds itself.

Next month Britons will see their energy bills rise by 80 per cent as the persistently high price of gas on global markets feeds through to customers. Following earlier price hikes, this will raise the cost of energy to consumers to three times what it was just a year ago. And this process has not ended. Under Britain’s regulatory regime, energy prices are due to rise again over the next six months, with independent forecasters predicting that by next April prices will reach almost 600 per cent of their level a year ago.

The impact on British households can hardly be exaggerated. Next month’s increase will take a typical household’s energy bill to £3500 a year. With the UK median income standing at just over £31,000, that will mean half of all households paying over 10 per cent of their income on energy, which is the official definition of “fuel poverty.” Around four million of the poorest households, including many pensioners and families, will see their energy bills rise to almost half of their disposable income.

Poverty campaigners warn that the inevitable result of these rises will be destitution, with households unable to heat their homes during the winter or children going without food (or both). Many elderly people are predicted to die of cold-related disease. The country’s most famous consumer champion, Martin Lewis, has described the situation as a “catastrophe.” It is widely expected that many households will be unable or will simply refuse to pay. Police forces are reportedly making plans to deal with civil unrest.

Over the past six months Boris Johnson’s government has provided some help to households to cope with rising bills, including a £400 payment to all, and up to £1200 targeted at those on the lowest incomes. But this was before the latest increases were announced, and the government is now under heavy pressure to do more. During her leadership campaign, though, Liz Truss insisted that her proposed tax cuts would be sufficient, and rejected the idea of further “handouts” to consumers.

Described as “a holiday from reality” by a senior Tory during the campaign, this position is not expected to survive contact with the real world once Truss is in Downing Street. Since income tax cuts will do nothing to support the poorest households, whose incomes are too low to pay the tax at all, it is clear they will not prove a publicly acceptable solution.

The Labour Party has argued that the new energy price increase should be scrapped altogether, with government picking up the tab for the costs. This would be partially paid for by a higher windfall tax on oil and gas companies, whose profits have soared during the crisis. Perhaps unsurprisingly, its approach is hugely popular, including 85 per cent support among Conservative voters.

It is therefore now widely expected that Truss will abandon her campaign stance and provide further help to households. A version of Labour’s approach is considered likely, with energy prices ordered to be frozen. The policy will be paid for by a mixture of public spending and a long-term financing scheme in which consumers will pay gradually for higher bills over a period of ten years or more. The government outlays will blow a further hole in the government’s budget. Truss’s team has already hinted that other areas of public spending will have to be cut, and — in a major reversal of previous Tory orthodoxy — public borrowing will need to rise substantially.

Will this spending be enough to give Liz Truss the kind of voter honeymoon usually granted to new prime ministers? Few observers think so. Having focused her leadership campaign entirely on policies designed to please Conservative Party members, Truss has said very little about other aspects of the immediate economic crisis Britain faces. With inflation running at more than 10 per cent and still rising, Britain is in the middle of a wave of strikes as workers across the economy seek to prevent further cuts in their real incomes. The Trades Union Congress has even mooted the idea of a general strike.

Meanwhile, soaring energy bills are likely to lead to a wave of company failures over the coming months: one study suggests that as many as 70 per cent of British pubs could be forced out of business. The Bank of England forecasts that Britain is about to enter a recession that will last the whole of 2023.

Liz Truss enters Downing Street with the Conservatives 9 per cent behind Labour in opinion polls. Translated into parliamentary seats, this would make Labour the next government, though not with an absolute majority. The two years before the next general election would be extremely difficult for the most gifted politician. Truss’s leadership campaign, conducted largely in a parallel universe, has left even her own supporters anxious. •