Before Lindsay, there was Parramatta. The Legend of Howard’s Battlers, that empirically unsustainable yarn that has blighted Australia’s political discourse for twenty-five years, has mostly cast the outer-western Sydney seat of Lindsay in the central role.

But it wasn’t always so. For the first eight years an even bigger star was Parramatta.

After the Coalition’s landslide 1996 victory, the fourth estate craved a compelling yarn about the whats and whys. Liberal apparatchiks provided one: John Howard, this down-to-earth everyman, had stolen Labor’s base. Ordinary, blue-collar, working-class Australians, fed up with Paul Keating and his grand visions about the arts and Asia and Indigenous affairs, had flocked to someone they recognised as one of their own.

And for the first few terms the legend was exemplified by that electorate with the instantly recognisable name. Most people, even in other states, had heard of the seat’s best-known suburb, Parramatta, around twenty-three kilometres west of Sydney’s CBD. It conjured (in 1996 at least) flannelette shirts, hotted up cars doing burnouts — you know, westies. The Liberals had stormed Labor’s heartland; it spawned a thousand opinion pieces.

Buried in the fine print was the fact that the electorate had mostly been won by the Liberal Party and its conservative predecessors since it was created at Federation; indeed, none other than Howard’s immigration minister Philip Ruddock was the local MP from 1973 to 1977. But over its life it has often been drastically reorganised by the redistribution knife, moving this way and that, favouring one side and then the other.

The Liberal candidate who won in 1996 was the religious, morally upstanding (at least publicly) and occasionally outspoken Ross Cameron. For the next eight years he was cast as the archetype of the Liberal MP the battlers now craved, a symbol of the new electoral landscape.

An unfriendly redistribution before the 2001 election threatened to send Cameron packing, but in the event didn’t. Shortly before the 2004 poll, though, he revealed that he’d had an extramarital affair, and “reporters in Canberra immediately ran with further details of Cameron’s private life, unleashing stories they’d been sitting on for years.” He was done for.

Parramatta moved back into the Labor column. The scandal had almost certainly made the difference.

With that seat gone, the focus on “Howard’s battlers” moved much further out, to Parramatta’s former understudy, Lindsay, around Penrith. (Fine print: created in 1984, it is best characterised as the kind of outer-suburban seat that tends to go to whoever forms government.) It was a much longer traipse for CBD-based journalists, but the tale thrived: values, conservativism and, best of all, the “Lindsay test”!

These two very different electorates serve nicely to illustrate the confused media presentations of “Western Sydney.”

Journalists’ sketches of this exotic species tend to oscillate. One day Western Sydney voters are all “aspirational” — (white) working class made good, often in well-paid trade jobs and perhaps owning a McMansion, many of them having fled to Sydney’s fringes.

The next day Western Sydney might signify immigrants from non-English-speaking backgrounds. They also aspire to good things for themselves and their families, of course, but they tend to have lower incomes, and the stereotype emphasises a religiosity and social conservatism that draws them to the Liberals. Recall Western Sydney’s relatively high No vote in the 2017 marriage equality survey.

The first cliché applies most of all to Lindsay, with one of the lowest populations from non-English-speaking backgrounds in Sydney. But the bulk of Western Sydney — Banks and Barton (southwest), for example, and Blaxland, Chifley, Fowler, Greenway, McMahon, Reid, Watson and Werriwa — more closely approximates the second (and most of those electorates still vote Labor, albeit not as reliably as decades ago). See this AEC map.

Multicultural Parramatta, like neighbouring Bennelong, can be seen as West meets leafy North Shore. The Liberals do best in the wealthier northeast, near the border with deep blue Liberal Berowra. (Lindsay, by the way, supported marriage equality 56 to 44 per cent. Parramatta opposed it 62–38.)

Enough scene-setting. Last month Julie Owens, Parramatta’s Labor MP for the past seventeen years, announced her upcoming retirement. The seat last experienced one of those massive redistributions before the 2010 election, when Owens lost almost half her voters to Greenway and took in a big chunk of Reid’s. That added 3 per cent to her estimated notional margin, which came in very handy in 2013 when Tony Abbott led the Coalition to a big victory and Owens held on by just 0.6 per cent. A smaller redistribution in the next term added another 0.7.

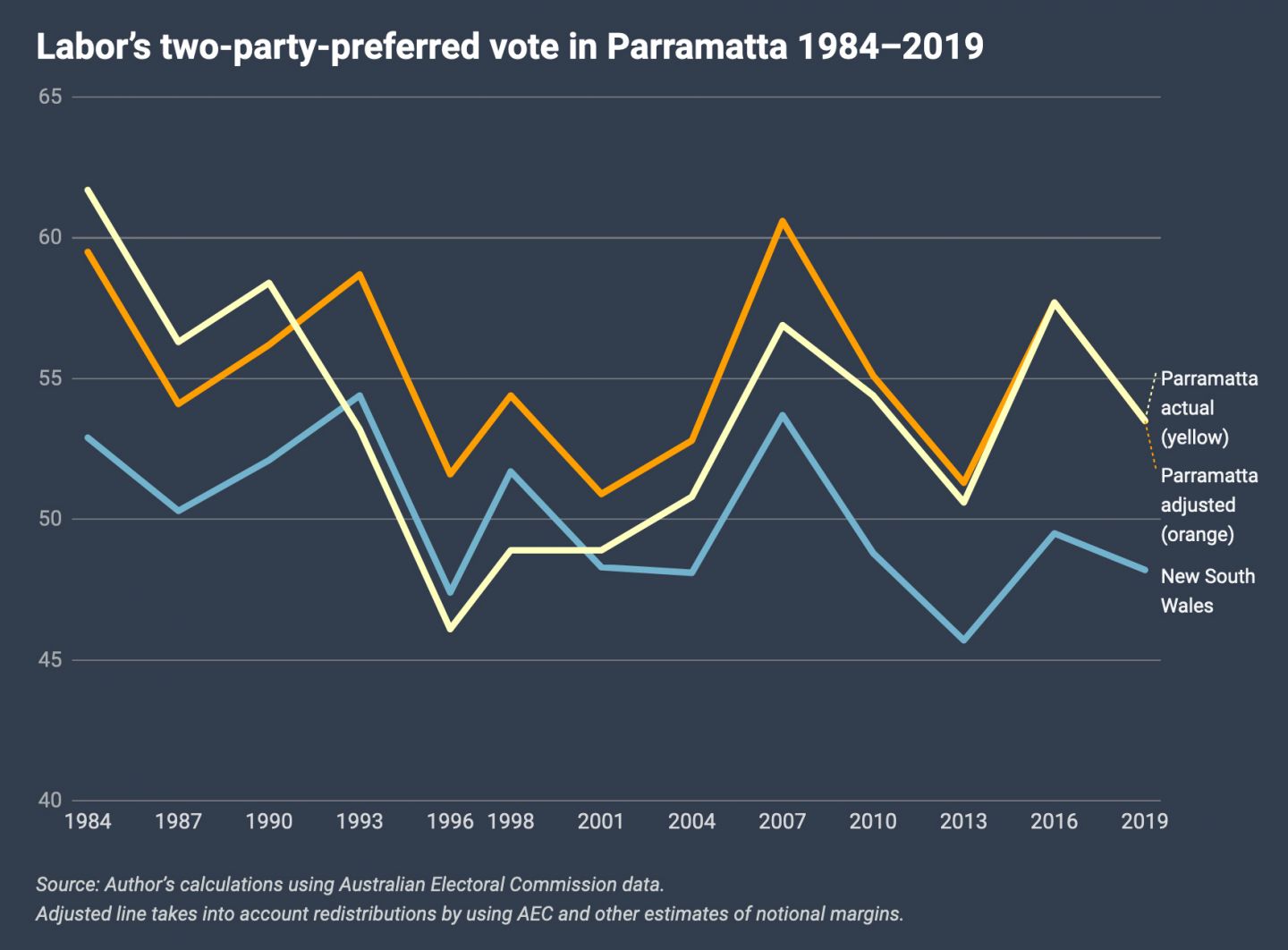

The upshot is that Parramatta is currently very Labor; and this chart suggests that under today’s boundaries the seat would probably have remained in Labor hands throughout the Howard years. (Several caveats apply, including demographic changes.)

Like much of Sydney’s west, Parramatta swung relatively strongly to the Morrison government in 2019. But then again it had swung to Labor (by even more) the election before.

I was expecting this piece to contain a rave about Owens’s big personal vote — she seems the type to have one, and since her announcement several colleagues have enthused about her enviable door-knocking prowess — but the evidence from the House-minus-Senate Labor votes doesn’t support that. The chart, in particular the gaps over time between the adjusted Parramatta line and the NSW one, lends at best modest support.

These are imprecise measures, but if it’s true that her personal appeal is not responsible for much of the 2019 Labor vote, that’s good news for her party, because the smaller her personal vote, the less it will be missed.

So the Liberals will certainly include Parramatta in their hit list (they routinely do), but it seems an unlikely gain.

Unless something unexpected happens in that part of Sydney overall. If we’ve learnt anything at recent elections, it’s that the unexpected should not be unexpected. •