Donald Trump has just created the biggest October surprise in American electoral history, and we won’t know for days or even weeks how dramatically it has changed the electoral equation. But the evidence still suggests that the Republicans are on course to lose control of the White House next month.

Even before last week’s news, commentators were being excessively coy about predicting the likely outcome of the election. All the indicators were pointing to a clear Biden victory, but most pundits are so scarred by their assumption that Hillary Clinton would win four years ago that they have been full of caution and caveats.

But 2020 is not 2016, and for months the likelihood of a Biden victory has been strong, even overwhelming. Before we get to why, it’s worth looking at the three main reasons why the pessimists have been urging caution.

• The electoral college is a majority-defying device that favours the Republicans

US presidential elections are decided not by the popular vote but by who gets elected as a state delegate to the electoral college. It is the majority of that body that determines who becomes president. In forty-eight states, the system is essentially winner-take-all, with all college delegates going to whichever candidate wins that state. In two states, Nebraska and Maine, it’s a bit more complicated.

The 538 electoral college votes are distributed on the basis of population size, but with the proviso that each of the fifty states, and the District of Columbia, are guaranteed a minimum of three. The magic number for victory is 270.

The outcomes in the popular vote and electoral college usually coincide, but not automatically so. At the moment the college’s composition gives Republicans an advantage. According to America’s leading psephologist, Nate Silver, only if Biden wins the national vote by three percentage points is he more than 50 per cent likely to win the college.

On five occasions, the winner of the popular vote has lost the election. Three of these were in the nineteenth century: in 1824 John Quincy Adams defeated Andrew Jackson; in 1876 Rutherford Hayes defeated Samuel Tilden; and in 1888 Benjamin Harrison defeated Grover Cleveland.

Then, in the first five elections of the twenty-first century, it happened twice more. Al Gore won half a million votes more than George W. Bush (48.4 per cent–47.9 per cent) in 2000 but lost the electoral college 266 to 271 (with one maverick vote cast). Then 2016 produced the biggest discrepancy of all. Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by 2.9 million votes but lost the election, and Donald Trump converted 46 per cent of all votes cast into 56.5 per cent of electoral college votes, giving him a winning tally of 304 to Clinton’s 227, with a few “faithless delegates” altering the balance slightly.

Using an institution like the electoral college to mediate the election of an individual leader, such as president, is counterintuitive. This arrangement was probably motivated by a combination of distrust of the public — whose worst instincts could be moderated by members of the college — and a wish to reassure the smaller states in the federation. And perhaps it made sense in the age of the stagecoach and the telegraph: in a country as large as America, regional variations might mean no clear winner emerged, leaving the college to broker an acceptable outcome. But with today’s national reach among parties, media and transport, this thinking no longer carries weight.

The electoral college is clearly an anachronism that distorts the democratic process. Some Americans resist the idea of moving to a simple count of popular votes because candidates would then concentrate all their activity on the big states, somewhat disenfranchising the small ones. But the current system gives candidates no incentive to increase their vote in states they think they have no hope of winning or are sure to win easily.

That’s why the disastrous wildfires that have raged along the West Coast won’t damage Trump’s re-election chances. His dismissive comments about their causes won’t have endeared him to voters there, but those states are already solidly Democratic. Perhaps the fires will give Biden bigger majorities there, but that won’t change any electoral college votes.

This means that the presidential campaign concentrates heavily on the swing states or, in American jargon, the purple states (between Democrat blue and Republican red). The two campaigns will concentrate their efforts principally on the dozen or so states where they think they have a chance of gaining (or a danger of losing) a majority.

A side benefit of abolishing the electoral college and going to a normal national plebiscite is that it would eliminate the potential impact of local corruption and abuses. Under the current system, parochial corruption can deliver a winner-take-all constituency, as it did in Florida in 2000; under a popular vote local abuses would be rendered irrelevant by the sheer size of the national vote.

• The polls can’t be trusted

The claim that the polls got it wrong in 2016 needs to be qualified. Clinton easily won the popular vote, and the aggregate of the national polls overestimated her vote by only one percentage point — a smaller error than the two-plus percentage points by which it underestimated Obama’s vote in 2012. The aggregate of national polls is usually fairly close to the national result, and the errors don’t consistently run in either party’s direction.

The problem in 2016 was that the polls failed to capture the distribution of votes. The key was Trump’s performance in three midwestern states — Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — all of which he won narrowly. Despite his large loss on the popular vote, they were enough to give him victory. Each had been Democratic in both 2008 and 2012, with Barack Obama beating John McCain by ten points or more in all three in 2008 (57–41, 54–44, and 56–42 respectively).

Neither the Democrats nor the national pundits gave these states much attention in 2016, and poor polling failed to set off any alarm bells. Simon Jackman and Zoe Meers at Sydney University’s US Studies Centre are among those who have tried to understand why, and they believe that one reason was the unusually large number of late-deciding voters, who broke heavily for Trump in the last week of the campaign. College-educated voters were more likely to participate in surveys, but those with less education turned out to vote in greater numbers than in the past and were largely supporting Trump.

Analysts are more aware of such traps this time, and are no longer prone to underestimating the degree of alienation among some groups in rust-belt states.

• Republicans don’t play fair and will try to sabotage the vote (and Donald Trump is capable of anything and will use all sorts of dirty tricks to avoid losing)

The United States is the only established democracy in which one major party has a strategy of making it difficult for likely supporters of the other side to vote. Donald Trump demonstrated the point when he remarked that if the Democrats succeeded in lifting overall turnout “you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.”

The United States also has no institution with the scope and authority of the Australian Electoral Commission. The power to conduct elections remains in the hands of state and local governments, which means that not only are electoral practices inconsistent but there are also more opportunities for local abuses, particularly those designed to make it harder for African Americans and poor people to register and vote.

Trump’s repeated claims about voter fraud are a calculated distraction. The nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice calculated the rate of voter fraud in three recent elections as between 0.0003 per cent and 0.0025 per cent. Even if it were concentrated in a single state, it’s hard to imagine that level of fraud having a material impact.

The much larger democratic issue is the number of people who want to vote but find obstacles in their way. Republican officials have reduced the number of voting booths in some voting districts where the Democratic vote is high, for instance, so that people get sick of waiting and go home. Republicans are planning “ballot security” operations in 2020, and the election could well see more incidents at polling booths than in any other election in modern times.

This is part of a pattern. Republicans have engaged in an increasingly shameless pursuit of partisan advantage since the early 1990s, no matter which conventions are overturned or double standards embraced. Their current determination to push through a Supreme Court nomination during the six weeks before the election is in direct contrast to their refusal to even consider filling the vacancy before the 2016 election.

Beyond the ruthlessness of Republicans, Trump’s recklessness can never be underestimated. Almost alone among leaders in a longstanding democracy, he purposefully attacks the integrity of the process, potentially undermining the trust that underlies the functioning of democratic institutions. When it seemed he would lose the 2016 election he made accusations of vote rigging; afterwards, he claimed baselessly that three million undocumented immigrants had cast fraudulent votes for Hillary Clinton. He has already denounced the integrity of the voting process for this year’s election and refused to say he would exit peacefully if defeated.

His special target this time has been mail-in voting. Long an uncontroversial part of the American electoral process, it could play a much larger role in 2020 because of the pandemic. Polls suggest more Democrats than Republicans will opt to vote by mail, and so Trump has repeatedly targeted the process.

The likely increase in mail-in voting does raise the possibility that the result will not be known on election night, and that later counting could peg back what appear to be Republican majorities in some states. This would be ripe territory for conspiracy theories and accusations of foul play. The best protection against such inflammatory possibilities will be a clear Biden victory.

Any country capable of electing Donald Trump once is capable of re-electing him. But even if we accept the broad validity of the foregoing concerns, several countervailing points add up to a compelling case for optimism.

• The polls have consistently had Biden ahead by a considerable margin, and there is every reason to expect that to translate into a high vote

Nate Silver’s aggregation of the national polling at FiveThirtyEight has had Biden leading Trump by 7 per cent or more since early June. Despite all the dramas and fireworks of the past several months, Biden’s lead has been constant.

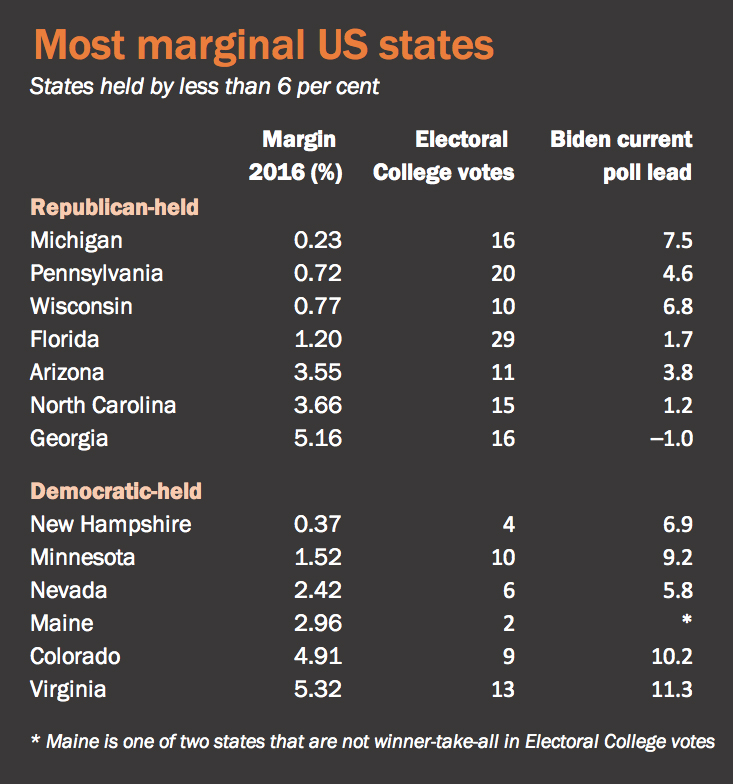

He has been clearly ahead not only in the national polls, but also in state polls carried out in the battleground states. The figures in this table strongly suggest he will hold all the states won by Clinton in 2016, and as of late last week he was leading in six of the seven states won most narrowly by Trump in 2016.

Source: final column is from Nate Silver, “What State Polls Can Tell Us about the National Race,” FiveThirtyEight

Jackman and Meers report that far fewer people are undecided than in the last three elections, which leaves much less room for a late surge to Trump. Sixty days from the election in 2016, 8 per cent of polling respondents described themselves as undecided; this year only 2 per cent did. This finding is consistent with the remarkably small variation in Trump’s approval ratings. Since 2017, according to RealClearPolitics figures, Trump’s approval rating has moved in a strikingly narrow band, with a high of 44 per cent and low of 38 per cent and disapprovals always outnumbering approvals.

No matter what idiocy or outrage Trump commits, his approval never falls below that floor. Every time Trump has said something stupid or outrageous over the past three and a half years, the refrain has been that it will not harm him with his base. Even as late as this week, an ABC headline asked, “Will Donald Trump’s Voter Base Care about the New York Times’ Tax Return Allegations Ahead of the US Election?”

The electorally important fact, though, is not how stubborn his base is, but that he doesn’t seem able to reach beyond it. Even if his base remains intact, it’s only around 40 per cent of the electorate.

• Those who dislike Trump dislike him intensely and are very likely to vote

Trump’s polarising tactics served him well in 2016, energising his base. But equally, and increasingly, they have also energised his opponents. In 2016 many potential Democrat voters were unenthusiastic about the Clinton candidacy and stayed home. Although many are also likely to be unenthusiastic about Biden, they now realise how high the stakes are.

Voting turnout in the midterm Congressional elections jumped from 41.9 per cent in 2014 to 53.4 per cent in 2018, the highest figure in four decades. Despite the obstacles posed by the pandemic and partisan obstruction, that figure suggests an aroused and engaged electorate, ready to go to the polls in large numbers in November.

• Demography is running against the Republicans

Inside Story’s Lesley Russell has observed that forty-seven million Americans aged eighteen to twenty-nine will be eligible to vote this year, and for fifteen million of them it will be their first chance to vote for a president. In the 2018 midterm elections, two-thirds of that age group voted Democrat. As the US Census Bureau has noted, these younger voters turned out in larger numbers than in earlier elections: up from 20 per cent in 2014 to 36 per cent in 2018.

The Republicans have benefited in recent elections by appealing to those who feel displaced by the changes happening around them. But defying the demographics can only succeed for so long. The United States is steadily becoming more racially and ethnically diverse, more educated and more secular, with women increasingly taking on leadership roles. With each passing election, these trends become more important.

• The looming election has increased the stream of bad news for Trump

Governments seek to roll out good-news stories in the lead-up to an election, but Trump’s capacity to do this has been very limited. Instead, the election has set a deadline for others wanting to release embarrassing material about him.

The market for books about Trump is obviously much larger before than after he leaves the White House. Recent weeks have seen the release of highly critical books by Trump’s niece, Mary, by America’s best-known journalist, Bob Woodward, and by Trump’s former lawyer, Michael Cohen. In the media, various reporting projects have also come to fruition: a Washington Post investigation showing how Trump, facing financial disaster in 1990, took control of his dying father’s will; a Channel Four report showing how the Trump campaign tried to discourage African Americans from voting in 2016; and, most importantly, the New York Times release of Trump’s tax returns for almost two decades.

Finally, the election is the deadline for groups keen to make known their discontent with Trump. Late last month, for instance, fifty former national security staff declared that he was unfit for office. Perhaps there will be more nasty surprises to come.

None of these is likely to swing large numbers against Trump. But they will provide an ongoing reminder of just how chaotic and worrying the past four years have been.

• Running as an insurgent incumbent is more difficult than running as an insurgent outsider

Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric has been undiminished, but it may well be less effective than it once was. In 2016 it allowed him to dictate the tone of the contest with Hillary Clinton, rendering her mastery of policy detail irrelevant. But what was novel in 2016 has become cliché by 2020. In July the Washington Post reported it had documented Trump’s 20,000th false or misleading claim since he became president.

More basic, though, is that voters’ expectations of a leader differ from their expectations of a challenger. Trump made little attempt to make the transition from the latter to the former. Leaders are expected to unite; Trump’s divisiveness has been unrelenting. Leaders must show achievements, not just make promises; Trump has preferred to simply assert the greatness of what he has done and offer no real program for his second term.

Moreover, he has had to take some responsibility for the state of the country. In his inauguration speech he spoke of American “carnage,” the high rate of crime, the lack of jobs in some areas, and similar themes. Raging about recent riots in Democrat-controlled cities is more double-edged. He has effectively been confessing to his inability to change such things.

While we weigh these political pros and cons, it’s important to remember that this election is also unprecedented because it is being conducted in the midst of a pandemic that has already claimed over 200,000 American lives, around four times the number of Americans killed in the Vietnam war. Seven and a half million cases have been recorded, two and a half million of which are still active, including most famously Donald and Melania Trump.

Trump’s response has been a bewildering failure of leadership. He has been unable to lead a coordinated and constructive public health response and unable to empathise with victims, has acted the part of a snake-oil salesman, and has frequently made false forecasts about the pandemic’s imminent passing.

Two-thirds of Americans disapprove of his handling of the pandemic, and Pew Research found that 87 per cent say they are dissatisfied with the direction of the country. Whether or not a Covid-19 vaccine is developed, a majority of Americans now seem immune to Trump’s gimmicks and lies.

None of this has diminished his capacity for self-congratulation or divisiveness. “If you take the Blue states out, we’re at a level that I don’t think anybody in the world would be at,” he said recently. “We’re really at a very low level.”

The campaign is now engulfed in uncertainty, and more drama is sure to come. But a look at the basics suggests that by far the most likely result is a Biden victory. If anything, the polls have got worse for Trump since last week’s debate, and there are no signs of a sympathy vote since his diagnosis. The Republicans are certain to lose ugly — with false accusations, recriminations, and attacks on the integrity of the election — but the overwhelming probability is that their candidate will lose, and lose by a sufficient amount that no dirty tricks will be able to overturn the result. •