Recent political events in the United States have improved the chances of meaningful global action on climate change in the medium term. It’s a small improvement, you wouldn’t want to overstate it, but things do look a bit more hopeful than they did last week.

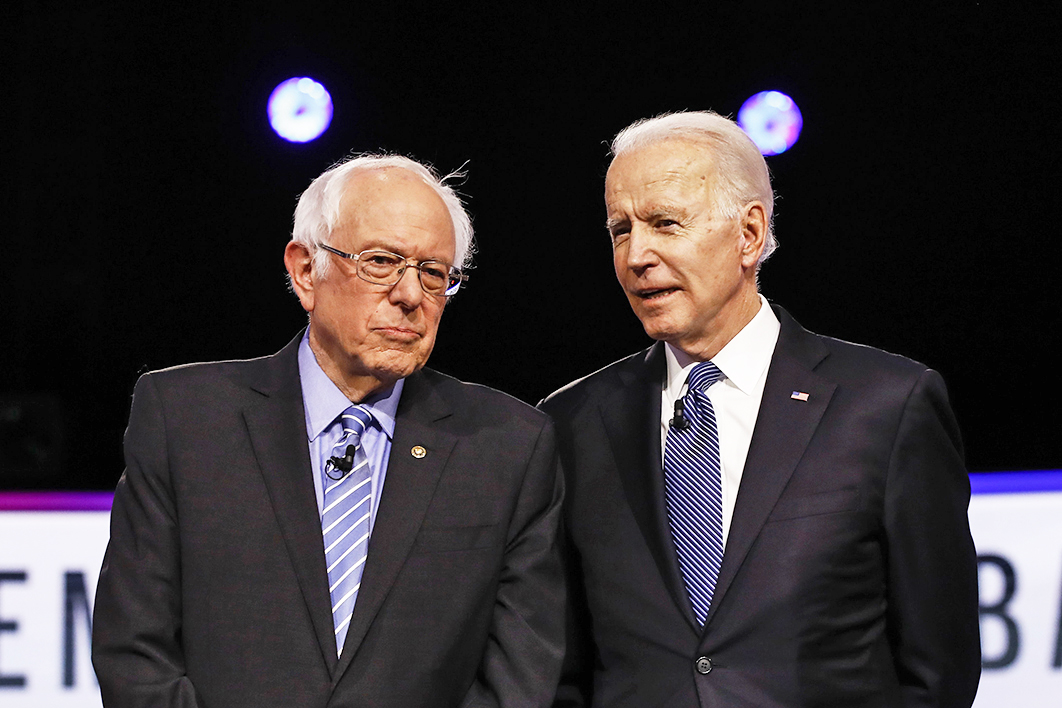

Joe Biden’s better-than-expected South Carolina primary, followed by Pete Buttigieg’s and Amy Klobuchar’s decisions to drop out of the primaries (Tom Steyer’s departure might also fit this bill), leaves the former vice-president as the sole occupant of the bland, don’t-scare-the-horses lane. This narrows his odds of becoming the eventual Democratic nominee, which in turn raises the probability of a changing of the guard in November.

Why? Because the idea that anything approaching a plurality of Americans would vote for a self-declared socialist like Bernie Sanders, who is particularly vulnerable to attack on immigration and health, is very far-fetched, even against an incumbent as repellent as Donald Trump. Ending private health insurance (for example) isn’t necessarily a bad idea, but taking it to an election sure is.

Forget those head-to-head polls, Sanders versus Trump. Measuring hypotheticals can be interesting, but they are useless as predictors (see, most dramatically, 2016). And the logic that it took a radical insurgent, Trump, to defeat Hillary Clinton four years ago, and so another disrupter, Sanders, is needed this time fails on several fronts. As we saw in Australia and then Britain last year, the dynamics of one election (2016 and 2017 respectively) don’t necessarily carry over into the next. And in 2016’s America there was no sitting president and the Democratic nominee had been deeply unpopular for more than two decades.

Now it’s President Trump. All I’ve read about Sanders’s strategy for generating turnout and winning back the “white working class” seems to assume that everyone who voted for Clinton in 2016 will simply vote for Sanders in 2020, and he can add these new supporters to the mix. As if millions of moderate voters won’t run a mile. As if “never Trump” couldn’t become “even Trump is preferable to Sanders!”

Biden boasts flaws galore: he’s about a hundred years old, is not necessarily very bright and was a gaffe machine even before senior moments joined his repertoire. But he promises a return to normality in the White House — not necessarily what Trump devotees crave, but probably what the majority of the voting public longs for.

And a Democrat (perhaps — a person can only dream — with a Senate majority) is more likely to act on climate change than a Republican, and certainly much more than Trump. Biden’s stated plans on this front are reasonably wishy-washy, but this is just an election manifesto. When it comes to pushing other countries to act, he talks of persuasion. But there is a better tool available: economic clout.

America accounts for around 15 per cent of the world’s emissions, about the same as its share of global GDP. But what it also has (admittedly in declining quantities) is power and influence.

Expecting countries to take responsibility for their own emissions has turned out not to work. The most common tool, pricing one’s own carbon (explicitly or implicitly), is just too difficult for nations to embrace with enthusiasm. The freeloader incentives are too great. Australia presents an extreme example of selfishness on this front, but very few countries are putting in the required yards.

As I’ve discussed before, the world has been going about this all wrong, expecting nations to cut their own emissions exclusively, rather than help force other countries to cut theirs. If global agreements had prioritised consumption rather than production, we might have made more progress: it’s politically easier, much easier, to penalise other nations for their greenhouse gasses than to penalise yourself. In economic terms, complementing a domestic carbon price with border carbon adjustment would shift much of the responsibility, and pain of change, onto others.

If China (25 per cent) isn’t going to take its greenhouse gasses seriously, for instance, let Australia at least whack a levy on the carbon in its exports. If it turns around and starts doing the same to us, that’s good for the planet too.

The European Union, which already has an emissions trading scheme, is talking about such a plan. Some American policymakers have long been interested in border adjustment as a general protectionist measure. If America also started pricing its own carbon — protecting its competitiveness by pricing the carbon component of imports, and subsidising exports to eradicate the effects of their price — we’d have about 30 per cent of the world not only pricing its own carbon, but punishing others (like Australia) that don’t.

(In 2015 Sanders put forward a bill to create a carbon price at the point of fossil fuel extraction, along with a border carbon adjustment — but on imports only.)

Most orthodox economists hate these schemes because they walk like protectionism and quack like protectionism. The last big trade war, in the 1930s, exacerbated the Great Depression. The Business Council of Australia, which is showing admirable leadership in advocating zero net emissions by 2050, and even going so far as to urge a carbon price, calls it “carbon protection.” (Obviously this lobby group is not to be confused with the outfit of the same name that cheered the Abbott government in 2014 as it terminated a well-functioning price on carbon.)

But pricing carbon is good. We want countries to do it. So a carbon trade war, with nations retaliating by pricing carbon, might be just the ticket.

Border carbon adjustment would be messy, with its fair share of unintended consequences. But any unilateral attempt to price carbon risks the big daddy of potential unintended consequences: pushing production offshore to countries with lax standards, with the possible end result of increased global emissions. In the long run we are either all dead (or suffering the horrendous humanitarian, ecological and economic consequences of continuing global warming) or we’re all (or at least the big per capita emitters) pricing carbon. The more countries that price carbon, the more those unintended consequences disappear.

So bring on the carbon protection and bring on the carbon trade war.

There’s another, much more heavy-handed alternative: Europe and America levying straight-out tariffs on countries not pulling their weight. Unlike border adjustment, this would take into account greenhouse gas emissions produced for domestic consumption, the most important of which is for electricity. We in Australia would be hit particularly hard.

The planet’s approach to global warming is in desperate need of a big shake-up. Fingers crossed for 3 November. •