The Hungarian composer Béla Bartók and the Australian Percy Grainger were contemporaries. They were both fine concert pianists, Grainger having the edge, and both ended their days in the United States. They were also among the foremost collectors of folk music, Bartók in Eastern Europe, Grainger in Scandinavia and the British Isles. The musicologist Malcolm Gillies has published extensively on each, so I once asked him to rate them. He didn’t hesitate: Bartók, he told me, was a great composer, among the five or six greatest of the twentieth century; Grainger wouldn’t make the top hundred. But composers can be fascinating, of course, even if their art is not of the top rank.

The Englishman Gerald Finzi (1901–1956) was another minor figure in twentieth-century music, and Diana McVeagh, who has edited a massive, 1080-page, two-kilo volume of the composer’s letters, is as clear-headed and unsentimental in her estimation of his importance as Gillies was about Grainger. But the book, if unwieldy, is fascinating for its glimpses into not only the creative mind of a lesser composer and his circle, but also a time and place.

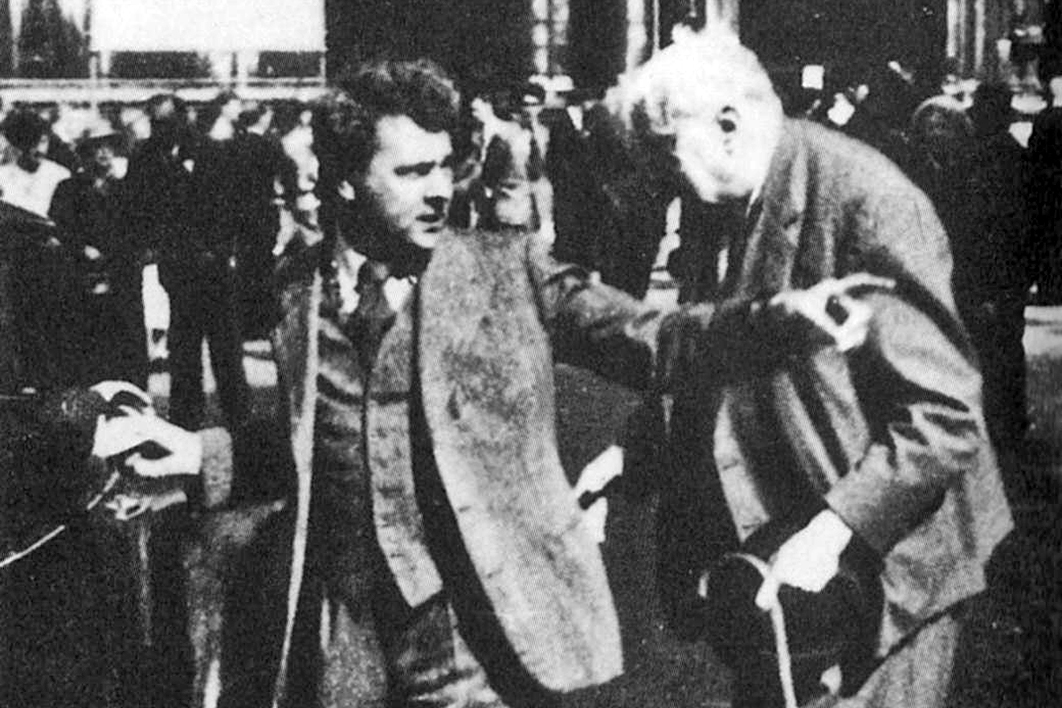

McVeagh, who will turn ninety-five next month, is a significant figure in English musicology. A decade ago she published a life and works of Finzi, and all the way back in 1955 a similar study of Elgar. Indeed, near the end of her edition of Finzi’s letters, she makes a cameo appearance when her Elgar monograph receives an encomium (“first rate”) from Finzi himself in a letter to his friend, Cedric Thorpe Davie. Later there’s a letter from McVeagh to Finzi — in reply to what one assumes was more direct praise of that book — and finally a note to McVeagh from Joy Finzi, the composer’s wife, following her husband’s death. (Joy’s portraits of her husband and his friends illustrate the book.)

Though English to his bootstraps, and suspicious, as McVeagh puts it, of “abroad,” Finzi came from a line of Italian Jews. He was non-conformist in many ways — agnostic and, for the most part, pacifist — yet his musical style was conservative. His tastes were conservative, too, and these were shared by his friends. Part of the attraction of this volume is reading letters to and from Finzi that wrestle with the progressive music of Schoenberg and Stravinsky, Berg and Boulez. In Finzi’s case, it’s clear he really is trying to appreciate it all (“there’s no reason why we shdn’t appreciate Schoenberg & Walton”), though even when he gets it, his judgements can take you by surprise.

“See Stravinsky’s Noces if you get the chance,” he writes to fellow composer Howard Ferguson. “I liked it — not as European art, but rather in the same way as we shd like some curious oriental or asiatic music.” The language might be of its time, but it’s not an impossible judgement on this particular Stravinsky score.

More often he fails in his attempts to be ecumenical, writing to William Busch in 1942: “I wd rather listen to a deft, delightful, light, movement by Ed. German, or Fauré, or J. Strauss or Elgar than all the ponderous integrity of Bruckner or the constipated integrity of Schoenberg! (I tried Pierrot Lunaire the other night. It was deadly.)” Just in passing, one wonders how Finzi heard Pierrot in 1942, because the first recording of the piece only appeared in 1949. Perhaps he had a score. This was the single moment of puzzlement I had from a volume in which the editor seemed to have anticipated and provided answers for all my questions as they arose.

The bête noire for Finzi and his friends, however, was their fellow Englishman, Benjamin Britten, younger than any of them, undeniably brilliant and enjoying early success. “Britten is rapidly going to the dogs,” Edmund Rubbra writes to Finzi of the twenty-two-year-old; and of Britten’s Piano Concerto, “Seldom have I heard a work so empty & futile.” Britten’s opera, Albert Herring, is best “seen & not heard” (Ferguson to Finzi); St Nicolas is “twaddle” (Ferguson, again); Winter Words is “just awful” (the poet Edmund Blunden); and Les Illuminations is “just like soap bubbles. Iridescent & easily exploded.” That last judgement is by Finzi himself and he was evidently pleased with it, repeating it in letter after letter.

What Finzi and his friends had experienced that Britten hadn’t was the first world war, and perhaps that’s why they resented his blithe facility. Britten was only five at the war’s end; twelve years his senior, Finzi had lost two elder brothers in the fighting (a third had died just before it began), and it is hard not to feel that this coloured his musical outlook and drew him to the writings of Thomas Hardy, whose poetry would provide the texts of six of his nine song cycles. That Hardy would, much later, also be the poet of Britten’s Winter Words rankled with Finzi’s circle.

The other vital figure Finzi lost in the war was his first composition teacher, Ernest Farrar, killed in action with the Grenadiers at the battle of Épehy on only his tenth day in France. The letters bring it home. In April 1918, Farrar is writing to Finzi from barracks, asking for manuscript paper. In May he thanks him for it. In September, Farrar’s wife, Olive, writes to let Finzi know her husband has gone to France, and in October she acknowledges Finzi’s letter of condolence following Farrar’s death (“I feel so proud of him, & yet my grief is unspeakable”). That these letters should take up less than two pages of McVeagh’s fat volume makes the snuffing out of Farrar’s talent the more pitiful.

And then there’s this, in a 1923 letter from Finzi to his friend Vera Sommerfield: “Ivor Gurney has gone mad. It is the most terrible news I have had for five years. Overwork on top of shellshock. He may get better.” But he didn’t, and the editing and publication of Gurney’s poetry and music became a mission for Finzi. It was the same with the music of the eighteenth-century English composers William Boyce and John Stanley, and the Victorian Hubert Parry, lost causes all in the progressive twentieth century. Yet, “Why not appreciate a Bartók… and a Parry?” (Finzi to his younger colleague Anthony Milner).

Much of this book is concerned, as you would expect, with the business end of a composer’s life — concerts, broadcasts, publications, frustrations. At the heart of it is a fascinating to and fro between the composer and the publisher Leslie Boosey (“My dear Finzi,” “My dear Boosey”). It’s 1939, another war is coming and Finzi is desperate to get Boosey & Hawkes to take on Dies Natalis, his setting for high voice and strings of words by the seventeenth-century mystic Thomas Traherne, in time for its first performance at the Three Choirs Festival. Boosey is being hard-headed, insisting it is not a commercial proposition. At length, Finzi more or less agrees to fund the publication himself. Then both premiere and publication are shelved for the duration of the war.

That correspondence is fascinating partly because we know now what neither correspondent knew at the time — that Dies Natalis would become Finzi’s best-known piece — and partly because it has the ring of high-stakes negotiation (though, except for Finzi, the stakes were small), the letters pinging back and forth on a daily basis, almost as emails would today.

There is rather less space devoted to Finzi’s musical philosophy (Finzi’s fault, not McVeagh’s — most of his extant letters are in the book), which is a shame because when it comes it is touchingly revealing. Here he is, writing to his wife, about William Rutland’s biography of his beloved Hardy:

I’d like you to read it… & perhaps it will give you some idea of why I have always loved him so much & from earliest days responded, not so much to an influence as to a kinship with him. (I don’t mean kinship with his genius, alas, but with his mental make up). Here is a passage from the book “The first, manifest, characteristic of the man who wrote the Dynasts is the detestation of all useless suffering and his loathing of cruelty. The suffering that fills the world, and the thought that it is unnecessary, are to him a nightmare. This was the long tribulation of Hardy’s life.”

It’s impossible to read these letters and not conclude that this was also Finzi’s tribulation. And perhaps that explains not only the thick seam of regret that runs through even the composer’s most radiant music, but also why, in the century of Stravinsky and Schoenberg, it looks so wistfully backwards. •