In the United States, Europe and beyond, there is a lot of unease about the future of democracy. Will Donald Trump regain the White House? Will the Republican congressional minority, enthralled by Trump, imperil democratic Europe and possibly NATO itself, despite a recent vote for Ukraine aid? Will France or Germany fall to ethnonationalists and fascists?

Against this backdrop, Poland’s parliamentary elections and the selection of Donald Tusk as prime minister last October offered a hopeful counterpoint. Voters embraced Europe and the world to rebuild democratic institutions torn apart by ten years of right-wing populist rule under Jarosław Kaczyński and his Polish Law and Justice Party.

A new analysis offers encouraging details. A larger-than-normal turnout, driven partly by a motivated cohort of younger voters, was a triumph for democracy. The analysis comes from two of the authors of this piece, Lucas Kreuzer and Kamil Lungu, graduates of Georgetown University’s BMW Center for German and European Affairs. The Polish election recommitted the country to tolerance, democracy and Europe after a decade of right-wing, populist rule that had sought to dismantle democratic institutions and stigmatise marginalised communities.

With sixty-four countries holding national elections in 2024, including the United States, Britain, India and Europe for the European Parliament, recent democracy-affirming victories in Poland, Chile, Brazil and the United States in 2020 and 2022 are instructive.

Every country is, of course, unique, but the Polish success underscores how candidates can succeed at “winning for democracy.” Poland’s triumph of democracy did not rely on any secret sauce but on elements that can be replicated when animated by gifted leaders and energetic movements.

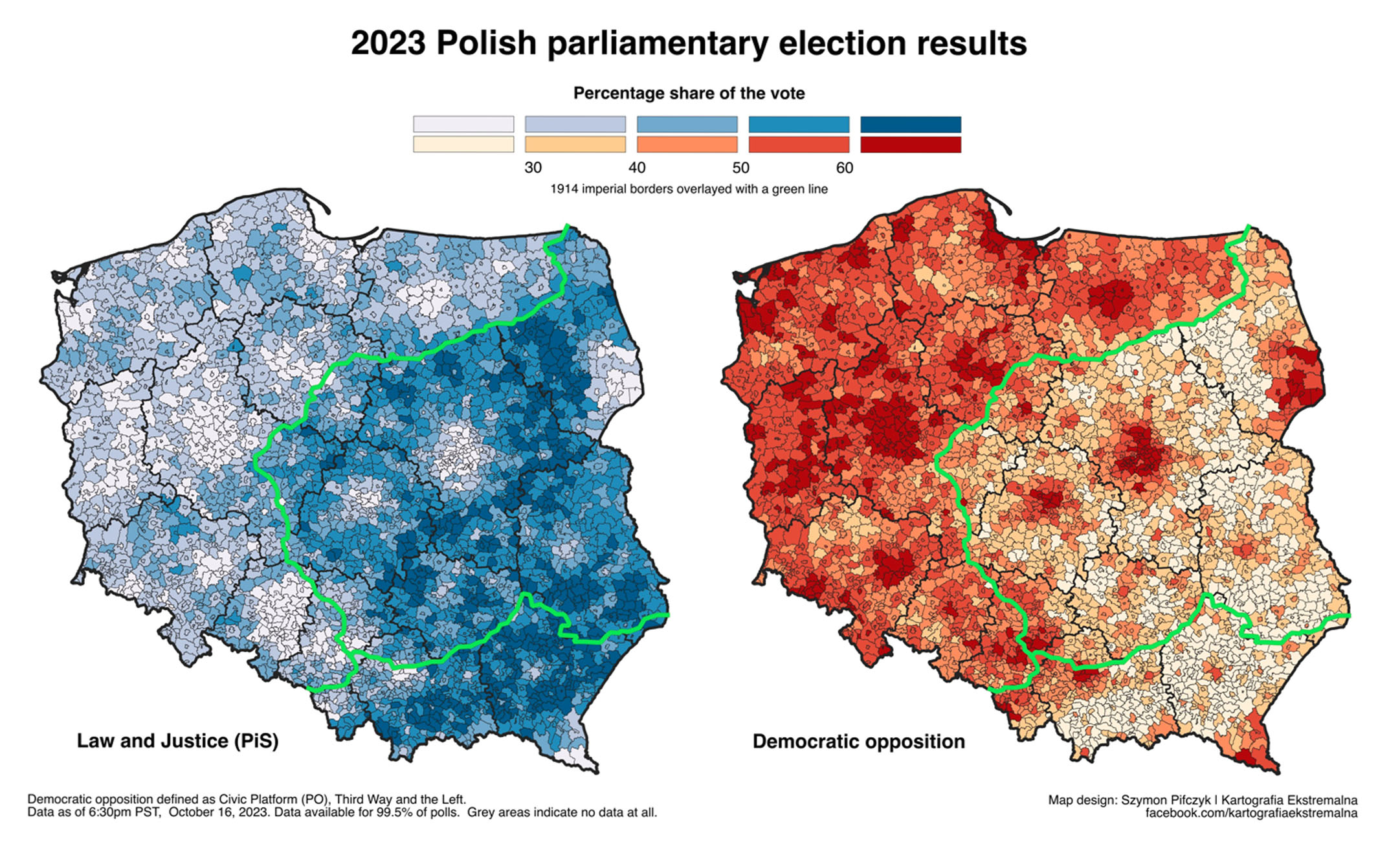

Like many other countries, Poland’s politics follow historical patterns and cleavages — including an east–west cultural and economic divide. Tusk was from the wealthy northern port city of Gdansk in the historically better-off western part of the country. In the past, Prussia controlled Western Poland, and as a result, the region was better industrialised and wealthier, with a more robust infrastructure.

In contrast, Tsarist Russia had overseen most of Eastern Poland, with Austria-Hungary also holding a slice. Under the imperial powers, Eastern Poland remained largely feudal and agricultural. While the eastern regions have slowly converged with the west, they are still among some of the poorest areas in Europe.

The historical divide also manifests itself culturally — for example, while Poland as a whole is overwhelmingly Catholic, residents of the east are more devout. In recent elections, Western Poland has overwhelmingly backed the Civic Platform and the other democratic opposition parties, and Eastern Poland firmly stands with Law and Justice.

The east–west divide echoes the urban–rural divide, with the former favouring the democratic Civic Platform and the latter supporting populist Law and Justice. For example, 48.2 per cent of Poles in villages voted for Law and Justice, while 43 per cent in cities with 500,000 or more residents voted for Civic Platform. The maps below illustrate these geographic divides with the 2023 election results. It superimposes Prussia, Tsarist Russia and Austria-Hungary’s historical imperial borders that informed Polish economic and political development.

The far-right Law and Justice Party exploited these cultural, economic and geographic cleavages to claim victories in the 2015 and 2019 elections. It wrested control of the state by appealing to a coalition of the ailing working class, union members, the old, religious people and inhabitants of small towns and rural areas — often those who have not benefited from economic liberalisation and European integration. It used its time in office to violate norms and reshape institutions to create an “illiberal democracy” that promoted what the party termed as “Polish,” “anti-Western” and “Catholic” values.

Knowing this, the winner, Tusk, campaigned more in the east and rural areas, helping diminish the gap in support for his party and coalition partners compared with the 2019 election. This tracks a similar strategy credited by several Congressional Democrats who bucked Trumpist support in their districts by winning and keeping their seats in 2018, 2020 and 2022. As Elissa Slotkin, a Michigan Democrat who has had repeated success in keeping her Trump-leaning Congressional district and is the likely Democratic nominee for an open US Senate seat, told us. “The key is to get out to the small towns and rural areas and lose less badly.”

In prior elections in the United States and Britain, Democrats and the Labour Party ignored the evolving political geography in their countries and suffered defeat to Trump, Brexit and the Tories. Blithely assuming their working-class, blue-collar supporters in the industrial Midwest and the North of England would hold, democrats in these countries missed the dissatisfaction with a national economy that not only didn’t lift all boats but left many high, dry and stranded. They then compounded the error by writing off many of these areas rather than trying to win back a sizable minority of these disaffected voters.

By contrast, the winning Polish coalition did not ignore, patronise or minimise the concerns of disaffected voters, particularly rural Poles anxious about prices and markets for their farm goods.

Instead, Tusk and his allies spoke directly about how their policies would economically lift and benefit all Poles. He spelled out the pocketbook benefits of the European Union, such as receiving the tens of billions of euros in funds frozen under Law and Justice. He also campaigned for more robust family support and stronger social policies such as a higher pension, a higher minimum wage and no tax raises.

A similar outreach and careful-listening strategy worked for Democrats (and democratic-minded Republicans) in Trump-leaning geographies. As detailed in the Washington Monthly, careful listening, addressing voters with respect, “showing up” and understanding what voters care about all helped Democratic congressional candidates make gains or even win in rural and small-town geographies otherwise carried by anti-Democrats like Donald Trump

It is also a successful path articulated by leaders in Britain like Greater Manchester mayor Andy Burnham, a Labour leader twice elected in a region that otherwise favoured Brexit-style anti-system movements. Visibly naming and sharing in constituents’ concerns, whether by riding a faulty transport system or by visiting growing homeless encampments — and then enlisting the community’s help and participation in fixing the problems — has gone a long way toward building trust.

Poles are proud of how their leaders successfully transitioned to democracy and capitalism, beginning with the Solidarity trade union movement during the cold war that led to communism’s downfall across Europe and the Soviet Union and reaching its pinnacle with its accession to the European Union in 2004.

No politician was better equipped to tap this Polish pride than Tusk, whose career echoed Poland’s democratisation and Europeanisation. An anti-communist organiser with Solidarity in the 1980s, he helped found Poland’s nascent democracy in the 1990s, established Civic Platform as a centre-right liberal, free-market, pro-European party in the early 2000s, was Poland’s prime minister between 2007 and 2014, and served as president of the European Council from 2014 to 2019.

Whatever pride leaders call on, national renewal strategies that build firmly on the identity of the people and their contributions are essential. Former Pittsburgh mayor Bill Peduto waxes eloquent about this, citing the fierce determination of German steelworkers he met on a recent European Study tour to build the clean, green future just as they had built the industrial past. He yearns for the kind of national leadership that would motivate Pittsburgh steelworkers, who are disaffected, disillusioned and today supporting Donald Trump.

In Sheffield, England, the mayor of South Yorkshire and other leaders have turned the community’s pride in being the invention centre of stainless steel into the pride of building the high-tech machines of tomorrow. In the United State, president Joe Biden’s investments in Detroit’s emerging electric vehicle industry and workers in the birthplace of the auto industry and the United Auto Workers mines a similar vein. Grand Rapids, Michigan, leaders describe their success in evolving and diversifying their economy from the furniture and car parts capital to a global hub of high-tech office, mobility and medical systems.

As Birgit Klohs, the German-born, long-time economic development czarina for West Michigan, told our recent transatlantic conference, “Build on who you are. Take it into the future, Diversify.” Finding this kind of success based on identity also keeps politics moderate and residents optimistic about the future.

In Poland, Tusk delivered a victory for liberal democracy, no doubt in part because Law and Justice overplayed its hand. The constant drumbeat of culture wars, political divisiveness and fighting with Brussels wore down the electorate. But the victory was undoubtedly aided by the fact that the Poles may retain a stronger attachment to democracy (and seeing many reap the economic benefits of European and world engagement) than neighbouring countries, such as Hungary, also experimenting with illiberalism. As a savvy politician and a sympathetic figure, Tusk capitalised on Poland’s fight against communism and turned to democracy as a point of pride and, ultimately, electoral victory.

Tusk’s Polish Civic Union and the other opposition parties campaigned to defeat Law and Justice, painting its tenure as a dark and damaging chapter to be moved past in favour of pro-democratic change and a bright and sunny future. Tusk went so far as to frame the election as “a battle between good and evil.” They also emphasised political and cultural moderation and an improved relationship with the European Union.

Tusk and coalition partners also tapped the values of tolerance and forward-looking orientation, particularly of young Polish voters. All this resulted in a voting turnout in which eighteen- to twenty-nine-year-olds overwhelmingly favoured Civic Platform, and voters between the ages of thirty and forty-nine expressed a slight preference for the Civic Platform. In contrast, voters over fifty strongly preferred the populist Law and Justice.

Other elections have seen the promise of hope and optimism defeat the politics of fear, repression and resentment. In 2021, Chile saw a new government sweep to power, with a record voter turnout pushing for a more equitable, inclusive and participatory democracy. President Barack Obama won the presidency twice on a clear message of hope over fear. Similarly, while likely to be tested again in 2024, the US electoral system held and pro-democratic forces defeated Trump-sponsored election deniers in 2020 and 2022.

Tusk and allies could overwhelm the educational, age and geographic divisions that brought Law and Justice in the past two elections by mobilizing the electorate’s young, pro-democracy, pro-Europe and pro-future elements. Other pro-democratic leaders and parties across the West would be wise to study his example.

Tusk’s victory — celebrated by masses watching on TV and together in auditoriums when the final parliamentary manoeuvring ended — was a joyous moment, wresting Poland free from Law and Justice’s hands after years of democratic backsliding. A key element of democracy’s triumph in Poland, and available in the parliamentary democracies that dominate Western political systems, is the reality of multiple parties competing equally and the need for coalition governance.

Just enough of the electorate responded to the Tusk coalition vision. Others soured on the Law and Order’s divisive politics, and Tusk was a strong enough candidate to renew Poles’ commitment to liberal democracy. A coalition of the three opposition parties — Tusk’s Civic Union, the Left, and Third Way — eked out a majority vote, 53.7 per cent, against the combined 42.6 per cent of Law and Justice and the Confederation Party, its ultra-far-right partner. Law and Justice still received a plurality of the votes (35.4 per cent) but lost a significant share compared to the last election. Civic Union gained enough ballots (30.7 per cent) to come in second and lead a new coalition government.

When facing authoritarians, democrats are aided by multi-party electoral and governance systems like this one. No similar result could occur in the United States, with its “winner-take-all” elections and Electoral College. If other candidates split the rest, Trump could win with as little as 35 per cent of the vote, as the Polish Law and Justice Party received in Poland. Coalition politics can be less of a buffer to strong, hard-right parties and candidates in countries like France, which has a strong presidency.

While these dynamics may be heartening to those fearing anti-democratic nationalist movements, the challenge is still real and frightening. But the Polish experience shows that savvy pro-democracy leaders who know their constituents, who offer hope and a brighter future, can carry the day. •

© 2024 Washington Monthly Publishing, LLC. Reprinted with permission of Washington Monthly.