International politics over the past year has taken on a distinctly 1930s flavour: a focus on Europe; an authoritarian leader seeking to bring real and imaginary kin into his fold; debates over economic sanctions; a war involving ground troops, artillery and tanks. The minds of Australian readers might well have turned to Frank Moorhouse’s Grand Days trilogy, much of which is set at the Geneva headquarters of the interwar League of Nations.

Canberra scholar James Cotton takes us back to those years in his new book, The Australians at Geneva, introducing us to a real-life group of talented people who worked in Geneva with the League and the associated International Labour Organization. He shows us how Australia’s role in world affairs evolved from the crass nationalism of prime minister Billy Hughes at the Versailles peace talks and in the years immediately after the first world war (“Who cares what the world thinks!”) to the ambitious internationalism of H.V. Evatt at the San Francisco conference after the second.

And what an array of Australian talent it was, working as League and ILO officials, support staff, visiting delegates to assembly sessions, and members of interest groups. As Cotton writes, “Geneva was Australia’s school for internationalism.”

Whether Hughes liked it or not, Australia had no choice but to engage with the League. At the insistence of American president Woodrow Wilson, colonies captured from the Germans and the Italians during the war had not been annexed to the victors, but were instead granted as League of Nations mandates, with sometimes tough conditions attached.

Australia was let off lightly, gaining relatively strings-free control of German New Guinea and Nauru. The government in Canberra wasn’t expected to grant early independence to either territory, or to open up two-way migration and trade.

But the Australian mandates didn’t altogether escape scrutiny. Why had a surplus in New Guinea’s public accounts been sent to Canberra rather than invested locally, came a query from Geneva. Why were workers in Rabaul on strike? How come explorer Mick Leahy was happily writing about shooting thirty tribesmen on his trek into the New Guinea highlands?

Canberra had other reasons for engaging with the League. It felt that a strong presence in Geneva could help ward off pressure on Australia to water down the White Australia policy, dismantle its tariff wall and submit to compulsory arbitration of disputes.

Despite the awkward queries, Australia came to see the League as a benign theatre, compatible with the emerging British community that came to be known as the British Commonwealth of Nations. Australia’s presence in the League — overseen by the high commission in London, which former prime minister Stanley Bruce headed from 1933 until 1939 — also helped extend its contacts to less familiar nations.

Former Rhodes scholar William Caldwell, a veteran twice wounded in France, was among the impressive Australians who took a senior role in Geneva, and he went on to feed the wider vision he gained there into the public debate back home. Having joined the ILO in 1921, he visited Australia a few years later to try to persuade sceptical state governments and employer groups to improve labour entitlements — though he received little help from trades halls convinced the ILO was a capitalist plot to divert workers from the revolution.

With states holding much of the responsibility for labour issues, Caldwell and another Australian with ILO experience, Joseph Starke, were among the first to suggest that the Commonwealth could use its treaty-making powers to intervene. The pair’s arguments were first tested in the High Court in 1936 and finally used successfully in 1983 to stop Tasmania’s Franklin Dam.

As his remit in Geneva extended to “native and colonial labour,” Caldwell also kept a file on the treatment of Aboriginal employees. In a 1932 letter found by Cotton, he wrote that “Australia is shamefully neglecting her obligations towards that dispossessed race.” Progressives like Mary Montgomerie Bennett were welcomed at the ILO, where they were able to raise the treatment of Aboriginal Australians.

Raymond Kershaw, another Rhodes scholar with a distinguished war record, joined the League at the end of 1923. As an officer in its minorities section he helped deal with the grievances of subnational ethnic, linguistic and religious groups stranded in other countries after the contraction of Germany and the break-up of the Russian, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires. It was an insoluble problem and a thankless task.

Kershaw left the League in 1929 to join the Bank of England. In 1930 he accompanied the bank’s Sir Otto Niemeyer on his mission to crack the fiscal whip over Australia’s “feckless” Depression-era state governments. Kershaw at least wrote papers arguing that the pain of Niemeyer’s prescriptions should be shared rather than fall mainly on the unemployed and poor.

Another Australian, Duncan Hall, had studied at Oxford during the war and completed the equivalent of a doctorate on the future of the Commonwealth. With Fabian socialists Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb and Leonard Woolf, he had done much to popularise the idea of a grouping of like-minded nations that could be a model for — or the nucleus of — the League. Failing to get an academic position back in Sydney, he joined the Australian delegation to a new regional body, the Institute of Pacific Relations, run from Honolulu.

From there he took up a professorship at Syracuse University in New York state, where he set up a model League of Nations among his students, a teaching simulation widely copied. On a visit to Geneva in 1927 he was invited to join the League’s opium section, which was trying to regulate trade in narcotics, as well as investigating child welfare and the trafficking of women.

Hall’s inspections and conferences took him out of Europe, to Iran, India and Siam (as Thailand was then known). In Calcutta he encountered erudite Indians who pointed out the double standard in the British Commonwealth: a higher status for the white dominions, a much lower one for the Asian and African colonies. The perspective he gained during the trip contributed to the emergence of an “Australian School” of international relations that looked beyond the Atlantic.

In the 1930s, Hall turned to psychology to explain the rise of mass movements supporting authoritarian regimes across Europe. He drew on the work of scholars, including the Austrian psychoanalyst Robert Waelder, who applied Freud’s concept of the “group mind” to the trend. Hall worried that advances in technology like radio were intensifying group consciousness, bringing people closer, extending mob oratory to entire nations and creating a collective psychosis.

At the League, Hall urged that a “realist” view of this threat should prevail over “Utopian pacifism.” His warnings were not welcomed by League secretary-general Joseph Avenol, who was ready to compromise with dictatorships. He barred Hall from making public addresses or broadcasts on his trips.

Another Australian in Geneva with a fascinating backstory was C.H. “Dick” Ellis, who arrived as a correspondent for a popular London newspaper in the late 1920s, and improbably wrote a heavyweight book on the League that became a standard reference. Ellis was also an MI6 officer, having served in the British army during the war, taken part in the anti-Bolshevik intervention in Central Asia, and studied languages at Oxford. He later became a friend of Australian external affairs minister Dick Casey, and in the early 1950s, by then very senior in MI6, he advised Casey on the formation of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service.

As Frank Moorhouse shows in his trilogy, the mood in Geneva shifted from the optimism of Grand Days, set in the twenties, to the gloom of Dark Palace, set in the thirties. The hopes of world disarmament foundered at a failed League conference in 1929. Japan annexed Manchuria in 1931 and withdrew from the grouping. Germany quit after Hitler took power in 1933, and other nations began pulling out. Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 was met with ineffective sanctions. Despite Wilson’s early enthusiasm, isolationism kept the United States out.

With the failure of peacekeeping, diplomats including Australia’s Stanley Bruce tried to keep the League useful by expanding its roles — not without a touch of national self-interest — in fields like health and nutrition. As Cotton remarks, “Bruce also considered that a world thus organised would be more receptive to exports of Australian agricultural commodities.”

In May 1939, with war becoming more likely, Avenol turned to Bruce to help rescue the League from its dire straits and the impasse on collective security. He asked the Australian to chair a committee to report on extending the League’s role in encouraging cooperation on health, social matters, economic affairs and financial regulation. By the time Bruce reported in August, his proposals had been overtaken by war. Avenol resigned to join the Vichy government in France.

An Irish deputy-secretary and a handful of staff kept a skeleton office going. After the war, however, Geneva was no more than an annex to the new, New York–based United Nations, though the city also became home to some of the agencies that took up the Bruce committee’s ideas, and the ILO continued to run from there.

Moorhouse’s novels picked up on a pioneering aspect of the League that Cotton also explores: the role of women. From the outset, the League declared all its positions open to female recruitment, though few women made it into positions more senior than the typing pool. Surprisingly, the otherwise conservative Hughes government decided in 1922 that Australia’s delegation to the League’s annual assembly should include at least one woman.

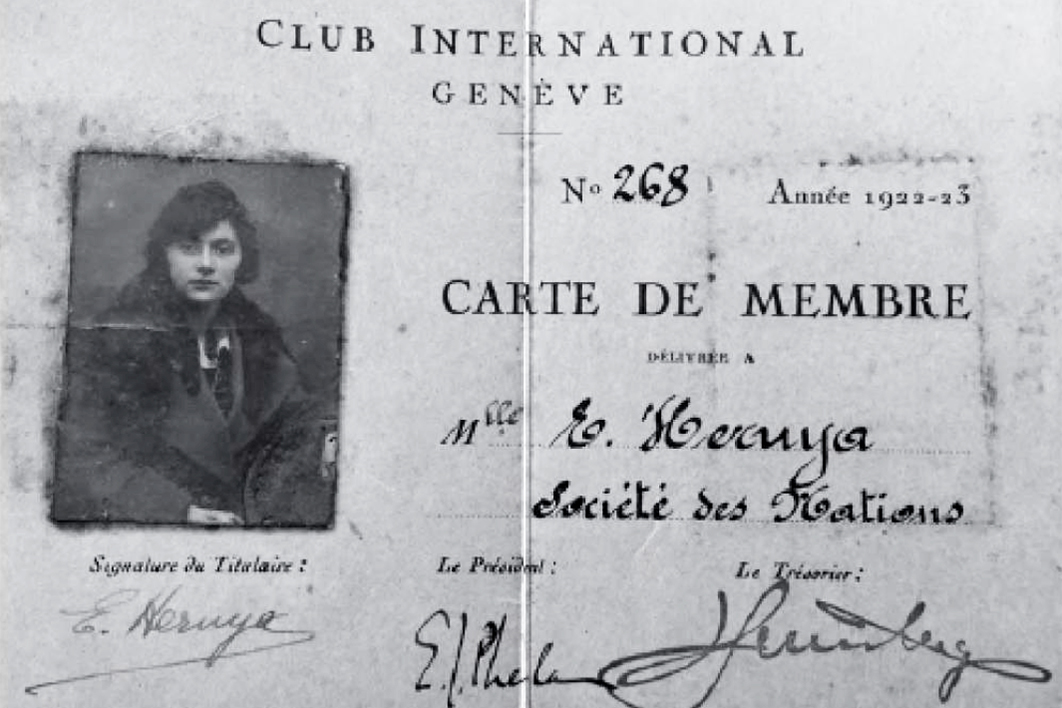

The League gave women like Emilia Hernya a role, albeit subordinate, and a voice.

In practice, the Australian women were only appointed as substitute delegates, not full members. When one woman asked her delegation leader what her role was, he responded, “Your business is to hold your tongue.” In 1927, women’s rights campaigner Alice Moss did stand in for delegate T.J. Ley, a federal MP and former NSW justice minister — as well as a confidence man and, later, convicted murderer — who had other things to do in Europe rather than attend a League committee in dreary Geneva.

Many of the women delegates had well-off spouses who could provide the funds for them to travel and agitate. Back in Australia they gave speeches and wrote articles about the League, often through the League of Nations Union branches that sprang up around Australia and across the world.

Bessie Rischbieth, the wife of a wealthy wool dealer in Perth, was an outstanding advocate of the League. In articles that still read well, writes Cotton, she pointed out how the effects of the Versailles treaty could be seen in the rise of the Nazis, and argued for a stronger League covenant, lower trade barriers, the abolition of exchange controls, and an open door to goods from colonies and mandates. As Cotton notes, “Seen in its context, Rischbieth’s assessment of the times was as comprehensive and insightful as any offered in Australia in the later 1930s.”

Melbourne woman Janet Mitchell was in Shanghai as a delegate to an Institute of Pacific Relations meeting in 1931 when the Manchurian crisis erupted. An Australian newspaper correspondent, W.H. Donald, persuaded her to visit Mukden (now Shenyang) and see for herself. She stayed a year in Harbin, a city teeming with Japanese occupiers and White Russian refugees.

Back in Australia Mitchell became a frequent broadcaster for the League of Nations Union, and in 1935 she was invited to join the League information section (probably by Duncan Hall, whom she had met at the 1925 meeting in Honolulu). She arrived in time to be disappointed by the League’s handling of the Ethiopia crisis. As she left Geneva, and the League, she wrote, “I began to see it, not as it was conceived by its founders as an effective force for peace, but as a little world born before its time, bound to fail.”

Ella Doyle, an Australian shorthand typist, moved to the League from the Australian Imperial Force staff in London. In 1937 she visited Germany and wrote an article about the Nazi crackdown on “decadent art,” pointing out that the works under attack were by the cream of modern German artists, one of whom had designed the stained-glass windows in the League’s new building. After 1945 Doyle had several UN engagements, and much later, in 1978–81, she was Australia’s first female ambassador in Dublin.

Alas, no one on Cotton’s list of Australians fits the character of Frank Moorhouse’s Edith Campbell Berry. Emilia Hernya perhaps comes closest, though her parents were Dutch and British and she was schooled in France. But she moved to Australia in 1913 and was naturalised in 1917 before returning to Europe and joining the League in 1920. Hernya’s childhood had been colourful: her parents worked near Paris’s Moulin Rouge nightclub where as a toddler — Cotton informed me by email — she is said to have sat on Toulouse-Lautrec’s knee and pulled his beard.

The model for Edith, Moorhouse confessed, was actually a Canadian, Mary McGeachy, who worked in the League’s information section. McGeachy left a huge volume of writing about the League and its time, which Moorhouse transferred into his character’s thoughts and speeches. She also appears in the novels as one of the real-life characters around Edith.

Though Hernya and McGeachy socialised in places like Geneva’s International Club, and no doubt had their love affairs, the model for Edith’s adventures on the boundaries of sexual identity was Moorhouse himself. Geneva provided neutral ground in more ways than one.

Moorhouse’s trilogy, an Australian classic unlikely to be added to a school reading list except by the bravest principal, is yet to make it to the screen as the film or series many of its fans have long anticipated. Two production groups have started projects but let them lapse. Meantime, I can attest that the trilogy is just as enjoyable on a second reading, and Cotton’s fascinating book amplifies the factual thread of Australian involvement. •

The Australians at Geneva: Internationalist Diplomacy in the Interwar Years

By James Cotton | Melbourne University Press | $39.99 | 246 pages