FOR AMERICAN writer Mark Danner the Bush administration defined itself forever when it responded to the killing of nearly 3000 people on 11 September 2001 by declaring a war on terror “unbounded in space or time.” A year into the Obama administration, the new president is trying to redefine the war on terror, “to shape it and to limit it,” but has had only partial success. Obama promised to close the detention centre at Guantanamo Bay and renounced the torture of terrorism suspects, but Guantanamo is still open and none of the architects of the Bush administration’s torture policy have been brought to account.

“We are in a state of exception, a kind of soft state of emergency, that has precedents in American history, during the civil war and the first and second world wars, but we have reached what I regard as a Nuremberg moment,” says Danner. “Torture remains legal, for all intents and purposes, in the United States. We have known about its use since the Washington Post ran a 5000 word investigation in late 2002 before the United States invaded Iraq.

“Most graphically we know about it from the photos of the hooded man and the leashed man among others at Abu Ghraib prison in 2004 and we know about it from the many government documents now publicly available on the internet. We remain in a state of exception. President Obama has not delivered us from it.”

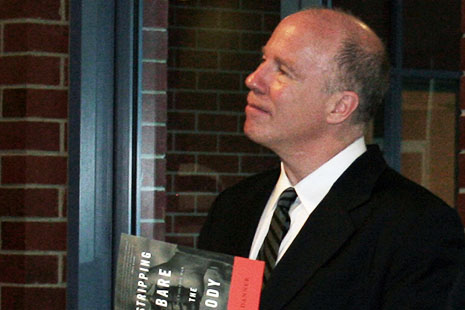

Danner, a professor of journalism and a longtime writer and analyst of American foreign policy, is in Australia speaking in Canberra, Melbourne, Brisbane and Sydney to coincide with the release of his latest book, Stripping Bare the Body: Politics Violence War. On Tuesday evening at the Australian National University he told his audience that one of the most disturbing features of the Bush administration was former vice-president Dick Cheney’s ability, almost singlehandedly, to wrench the Republican Party and many Americans around to his attitude to the use of torture against terrorism suspects.

“Cheney calls it ‘extreme interrogation techniques’ but we know that what he is talking about is torture. So the Republican Party’s attitude towards torture is now very clear: they’re for it. The Democrat position is not so clear. President Obama is clear; he says he will stop torture and will change official policy but when he’s asked about what will be done about those in the previous administration who drafted the infamous ‘torture memos’ and those who carried out the policies, he says ‘We will look forward, not back.’”

To Danner’s ear, this is a “pernicious phrase. If we follow this line no one would ever be prosecuted for anything. A Department of Justice report released in the last few days criticised the lawyers who drafted the torture memos but said ‘they do not deserve ethical sanction.’”

And it seems many in the United States agree. Danner points to an opinion poll released in April 2009 by the non-partisan Pew Research Center that found a majority of those surveyed (54 per cent) believed the use of torture against terrorism suspects was sometimes or even often justified. “This is the first time in over five years of Pew Research polling on this question that a majority has expressed these views,” the report found. “Another 16 per cent say torture can rarely be justified, while 25 per cent say it can never be justified.”

Conversely, a substantially higher proportion of people surveyed in twenty-one other countries opposed the use of torture, even when dealing with a “terrorism suspect who may have information that may save innocent lives,” according to a report released in November 2009 by the non-profit US body, the Council on Foreign Relations. Where the Pew survey put the percentage of Americans unequivocally opposed to torture at 25 per cent, the comparable figure in the council’s survey averaged across the twenty-one countries was 57 per cent. In Britain and France the proportion was higher: 82 per cent; in India and Turkey it was closer to the American figure but still higher, at 41 per cent and 49 per cent respectively.

IN PERSON, Danner seems like many a globe-trotting journalist. When I interviewed him last week, he lamented the fact that he was talking over coffee in Lindrum’s, a Melbourne boutique hotel, when he felt he should be on the ground in Iraq reporting on next month’s elections. “I haven’t been to Baghdad since 2007; I really should get back, but I’m here for this,” he said, waving his arm and referring to his visit to Australia to promote his book.

Despite holding dual professorships at the University of California in Berkeley and Bard College in New York, Danner primarily identifies himself as a journalist: “correspondent” is the term used on his business card. And when answering a question about how the Obama administration is dealing with Iraq and Afghanistan, he clutches his head as he remembers that Robert Silvers, his longtime editor at the New York Review of Books, is sweating on him to produce an article about President Obama’s approach to foreign policy. “I can feel this beam of his thoughts coming into my head even though he is half a world away. I’m talking when I should be writing.”

It’s through Danner’s writing, especially, that you begin to appreciate what a rare kind of journalist he is. Like many foreign correspondents, Danner puts great store in seeing things with his own eyes, even if that means getting dangerously close to violent events. Here, for instance, is a chilling moment from Stripping Bare the Body, when Danner, then twenty-nine, and other correspondents were in Haiti during the lead-up to a planned election in 1987 that followed the sudden exile, courtesy of a US government-provided aeroplane, of president Jean-Claude Duvalier. They are following a tractor-trailer carrying soldiers serving General Henri Namphy’s interim regime when it comes to an abrupt stop and soldiers leap out, charging at a small mud house.

“We had pulled up about fifty yards back and got out of the car; now we stood in the middle of the road, transfixed. All at once, the soldiers became conscious of us. They froze in their charge, then turned to face us. Everything seemed to stop: The slender young men in olive green stared at us over their automatic rifles, their faces impassive, and we stared back, pens poised over notebooks, cameras clutched at chest level. No one moved. Finally, very deliberately, the lead soldier moved his rifle in a wide arc, back and forth, at the level of our chests – once, twice, three times. That was all it would take. It would be that easy.”

There is a frozen moment; then the soldiers get back in their truck, leaving the journalists flat-footed on the road. Danner comments: “Whoever had been about to be beaten or killed would have at least a few more minutes to enjoy life in Botel.”

He goes on to describe a series of appalling massacres of Haitians by soldiers and the feared Tontons Macoutes militiamen as citizens set out to vote. The attacks forced the election to be abandoned. The events he describes not only shock but raise many questions about the impoverished island in the Caribbean, and this is where Danner differs from many foreign correspondents: on top of witnessing events, he spends an equal if not greater amount of time reading books and studying history to understand better the events he reports.

The value of his approach is particularly evident today, little more than a month after the earthquake in Haiti killed more people than died in the 2004 tsunami, prompting saturation global media coverage that within weeks slowed to a trickle.

In the articles reproduced in this book from a three-part series published in the New Yorker in 1989, Danner prods readers to look further than the daily news media’s necessarily superficial attention to the “spectacle” of chaos, ruin and grief that follows a natural disaster. Compare the opening of Time magazine’s 25 January cover story about the earthquake, which began “Tragedy has a way of visiting those who can bear it least,” with a piece Danner wrote for the New York Times on 21 January. Where the Time opening is glib and the magazine’s coverage confines itself largely to the natural disaster, Danner wants readers to appreciate that something more than our impulse to charity is needed if there is to be any real recovery in Haiti.

Danner is always looking to lay out resonant facts, such as how, in 1804, African slave-soldiers in Haiti led the only successful slave revolt in history, and how the neighbouring United States and other colonial powers not only imposed a crippling trade embargo on Haiti but required it to pay its former overseer reparations.

“The new nation, its fields burned, its plantation manors pillaged, its towns devastated by apocalyptic war, was crushed by the burden of these astronomical reparations, payments that, in one form or another, strangled its economy for more than a century. It was in this dark aftermath of war, in the shadow of isolation and contempt, that Haiti’s peculiar political system took shape, mirroring in distorted form, like a wax model placed too close to the fire, the slave society of colonial times.”

AS IS EVIDENT in the passage about the Haitian soldiers quoted above, Danner writes vividly about the events he witnesses, but unlike some he is never content simply to tell stories, let alone the hero-correspondent’s “war stories” about close shaves with death. He includes such material, he says, because the correspondent’s first task is to “tell what happened” even though being in the middle of violent political events is deeply confusing and offers the correspondent only a partial view.

The bulk of Danner’s articles include substantial analysis, much of it drawn from his reading, but also from interviews with experts and close study of primary source documents, in which he meticulously peels away the fly of government action from the fly-paper of government rhetoric.

Unlike many, Danner has long been committed to making widely available the primary source documents he writes about. When he converted to book form a lengthy New Yorker piece about a 1981 massacre of villagers at El Mozote in El Salvador, he included an additional 100 pages of documents selected from thousands of pages released years later by the Clinton administration. He also appended a list compiled by human rights investigators of the names and known details of the 767 villagers whose murder had been staunchly denied by the anti-communist Salvadorean government and by the Reagan administration.

Apart from the Haitian series, Stripping Bare the Body includes Danner’s reportage from the civil wars in the Balkans in the 1990s. But the biggest section is devoted to the Bush administration’s response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. He was among the minority of journalists in the United States who vocally opposed the US government’s plan to invade Iraq, including in widely publicised debates with high profile colleagues such as Christopher Hitchens.

In 2009 he obtained a copy of a Red Cross report about mistreatment amounting to torture of so-called “high value detainees” held in secret prisons operated by the Central Intelligence Agency around the world. Red Cross officials had interviewed the detainees in late 2006, and parts of their report had been revealed by other journalists, including Jane Mayer of the New Yorker, but Danner made the entire report available through the New York Review of Books.

He says he has learnt the necessity of restating even obvious truths. In the debate Hitchens’ arguments were predicated on there being a clear link between Saddam Hussein and the 9/11 attacks. “There was never any link between the two. I was thinking that it was so obviously crap that I did not need to refute it, but I did, because the more often it was stated, by Christopher, not to mention by President Bush, the more that many people believed it.”

More recently, he has been bemused by the absence of public anger toward former vice-president Cheney, who within ten days of Barack Obama’s inauguration began criticising the new president for renouncing the use of torture in the fight against al Qaeda. “Cheney has attacked Obama relentlessly for months now, as if the actions of the previous administration, of which he was a vital part, played no role at all in creating the tremendously difficult problems besetting Obama.”

It is hard to disagree, especially after reading the thirteen reports and essays on Iraq in Stripping Bare the Body, which lay out just how disastrous the invasion of Iraq has been, for Iraqis, for American troops and for global opinion of American foreign policy, through policies and practices that were both misguided and mismanaged.

From the decision to invade Iraq, grounded in spurious evidence of Saddam’s possession of weapons of mass destruction, to interagency brawling in the US government that meant there was no postwar planning, and from lying about whether torture was being used on suspected terrorists to re-defining torture as any interrogation practice that fell short of killing someone – these government actions, Danner argues, have caused and are causing incalculable damage.

For Danner the use of torture is repugnant, but beyond that he reminds us that a report commissioned by the administration after the Abu Ghraib photos were publicised in 2004 found that nine out of ten detainees brought to the prison were of “no intelligence value.”

He shreds the Bush administration’s stance on torture, which defended its questionable reliability in obtaining valuable information while lying about its use and misunderstanding how much damage it was doing to often innocent victims and to its stated policy goals. “One does not reach democracy, or freedom, through torture.”

Apart from anything else, the Bush administration’s policies, which reached their nadir in the Abu Ghraib scandal, played into Osama bin Laden’s hands. “What better image of Arab ill-treatment and oppression could be devised than that of a naked Arab man lying at the feet of a short-haired American woman in camouflage garb, who stares immodestly at her Arab pet while holding him by the throat with a leash?

“Had bin Laden sought to create a powerful trademark image for his international product of global jihad, he could scarcely have done better hiring the cleverest advertising firm on Madison Avenue.” •