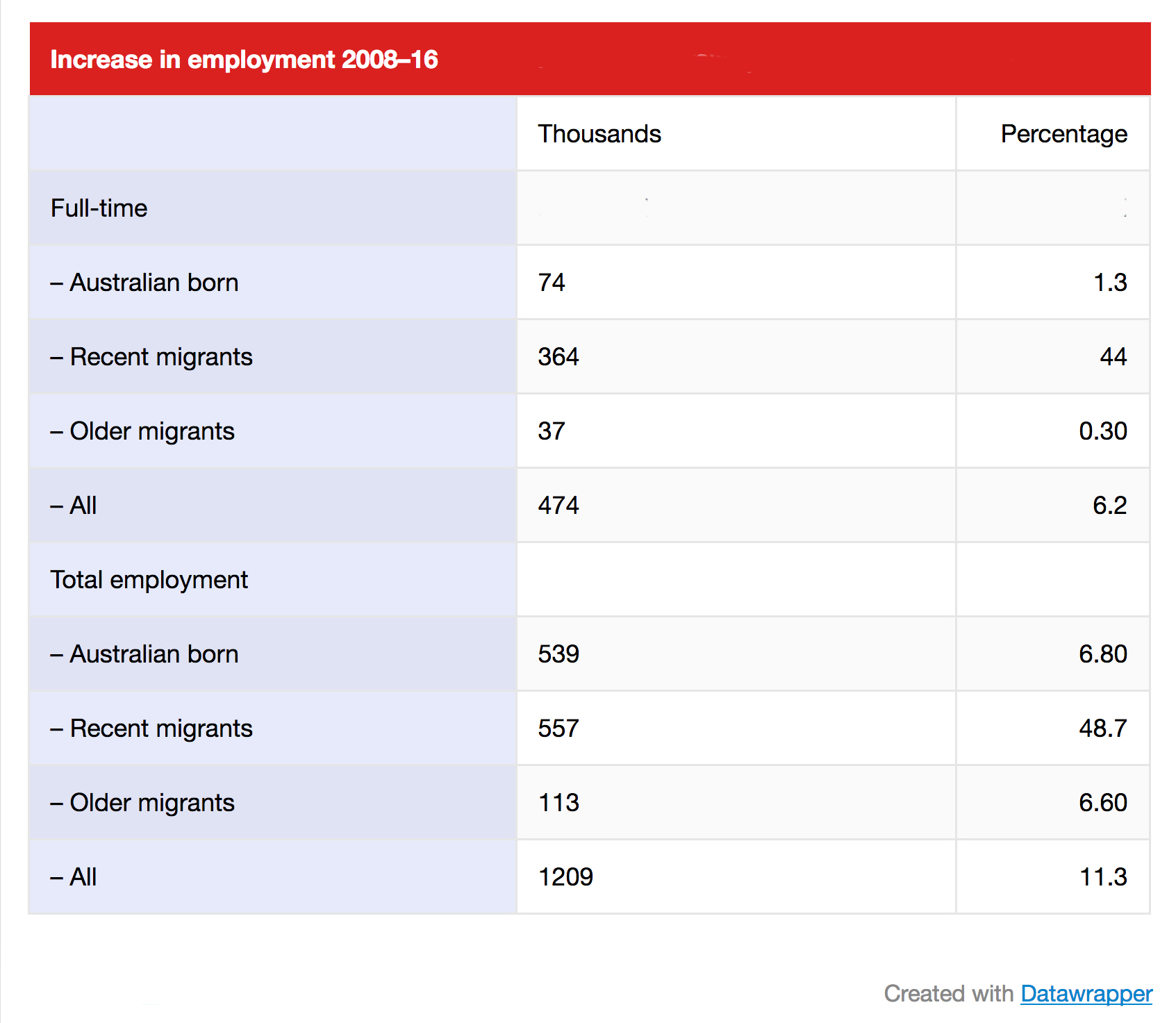

Between 2008 and 2016, in net terms, the Australian labour market expanded by 474,000 full-time jobs. But only 74,000 of them went to people born in Australia. That’s fewer than one in six.

That’s not because the Australian-born are a small minority. Two-thirds of all working-age residents of this country were born here. Yet roughly three-quarters of the growth in full-time jobs since the global financial crisis has gone to recent migrants.

Australian Bureau of Statistics figures ignored by analysts reveal that of those 474,000 new full-time jobs, in net terms, 364,000 have been filled by migrants who have arrived in Australia since 2001 – most of them since the GFC.

It is a stunning demonstration of why the Turnbull government had no choice yesterday but to flag the replacement of the 457 visa program, under which many of those migrants have arrived here. They have come from all parts of the world, but almost half are from one part: the Indian subcontinent. While only a net 74,000 full-time jobs have been generated since 2008 for workers born in Australia, a staggering 168,000 of them have been generated for workers born in India and its neighbours.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Numbers rounded to nearest thousand or 1 per cent. Recent migrants defined as those who say they have been in Australia less than fifteen years, older migrants as those who say they have been here fifteen years or more.

Some of those workers arrived here originally as students, but found ways to stay on in Australia, whether they are working as doctors and engineers or as taxi drivers, on late-night shifts at service stations or as kitchen hands in Indian restaurants. But many came here on 457 visas, brought out by employers who have been allowed to run their own immigration programs, with relatively little oversight by government.

The widespread flaws in the scheme have been meticulously documented by Bob Birrell and his colleagues at the Australian Population Research Institute, but generally ignored in the policy debate. Many on the left and centre-left seem to be uncomfortable with the idea that there can be such a thing as too much immigration.

I am unambiguously pro-immigration, but if the level and nature of the immigration are not working for us, I suggest we turn down the tap. That was the way immigration policy was run in the Menzies era. When the economy slowed, ministers turned down the tap of immigration flows, reducing numbers to avoid flooding the market. We need to do that now.

The 457 visas are only one part of the problem. Despite the clear downturn in the labour market since 2012, the federal government has maintained a target of 190,000 permanent migrants a year, two-thirds of them skilled migrants. We have more than half a million foreign students who are free to work, and at any time there are tens of thousands of visitors here on working holidays.

But the 457 visas have been so rorted by unscrupulous employers that they are now a damaged brand. Case after case has been exposed in which workers were mistreated, were not paid the wages required by law, or were employed in different jobs from those stated. There was minimal supervision by government, and it was all too easy for workers to convert their visa into permanent residency.

Bureau figures show that in the decade to June 2015, 371,000 “temporary workers,” plus their families, arrived here on 457 visas, sponsored by business, ostensibly to fill jobs that could not be filled by Australians. Yet over that decade, only 145,000 of those on 457 visas left Australia to return home. Roughly 60 per cent of them, 226,000, stayed in Australia, mostly swapping their temporary visa for permanent residency.

They want to improve their lives, and you can’t blame anyone for that. And if there’s room for them in the labour market, and they’re not costing our own kids jobs, then good luck to them.

But analysis of the labour market data shows that’s not the case. Between 2008 and 2016, the number of Australian-born workers who were unemployed swelled by more than half, from 338,000 to 507,000. The number of them in full-time jobs grew by only 1 per cent. The number unemployed and looking for full-time work grew by 54 per cent.

In particular, between 2008 and 2016, the number of fifteen-to-twenty-four-year-old school, college and university leavers who have a full-time job shrank by a massive 214,000, or 21 per cent. Sure, many stayed longer in full-time education. But the number of education leavers in part-time work jumped by 29 per cent, while the number unemployed shot up 36 per cent. They are the victims of a system that encourages employers to bring in skilled workers from overseas rather than hire and train them here.

That sums up in a nutshell why Malcolm Turnbull and Peter Dutton had to move yesterday to pledge that 457 visas will be replaced next year by two visas setting tougher conditions, including a requirement that employers must look for workers locally before seeking permission to import them.

The key changes are that:

• A new two-tier system will be introduced from March 2018, with one class of temporary workers given four-year visas with a pathway to permanent residency, and the other allowed two-year visas with a pathway just to a second two-year visa.

• Employers will be required to advertise first for workers in Australia, unless they bring workers from a country with a trade agreement that rules that out.

• Workers will have to show they have two years’ work experience, and pass a criminal history check.

• Employers using the 457 visa scheme will have to pay a training levy for Australian workers, with the details to be announced in the budget.

There are many questions to be answered and details to be filled in before we know how the new scheme will work. While the prime minister made much of the reduced occupations allowed to use the scheme, there are still some 400 of them – and they include all the main occupations for which 457 visas are now issued. Labor points out that the 216 occupations removed from the list would exclude less than 9 per cent of current visa holders.

What labour-market testing will be required? In what ways will the bar be set higher for issuing four-year visas with permanent residency rights, compared with the two-year visas, which exclude permanent residency?

And, most crucially, what resources will be devoted to ensuring that employers are abiding by the conditions of the new visas: using their staff for the duties they nominated, paying them the agreed wage, and so on? One reason why 457 visas developed into such a rort was that the federal government failed to police them. Employers who exploited their 457 workers seemed to be more at risk of being exposed by Fairfax’s Adele Ferguson and her colleagues than by the immigration authorities.

The key occupations that dominate the program will still be allowed in the replacement scheme: cooks, chefs and restaurant managers; ICT business analysts, programmers and software engineers; and the amorphous occupations of marketing specialists, sales and marketing managers, customer service managers, and so on.

Between them, over the past two years, just twelve occupations in these three areas accounted for more than a third of the visas granted. All of them are on the new lists. What difference will the tougher conditions really make when the new system takes effect? We’ll have to wait and see. But the key changes are good ones; if they do work in the way the ministers implied they would, they would help restore a balance that has been missing in immigration policy for years.

It’s not an encouraging sign that Turnbull and Dutton yesterday played it for political ends. Repeatedly, their statements were misleading or flatly wrong. The 457 visa was introduced by the Howard government, not (as they implied) by Labor. Bill Shorten, whom Turnbull called the Olympic champion in issuing visas, didn’t issue any at all; he was not the immigration minister. Labor in office tightened the rules of the scheme to reduce rorts – a crackdown the Coalition, and Turnbull personally, opposed.

Until recently, the Coalition’s only changes to the scheme have been to weaken its controls. It rejected advice from its own taskforce to set up an independent monitor to carry out labour-market testing, and to reduce the number of occupations using the scheme. It can’t claim credit for the fall in the number of visas issued; everything it did in office was designed to increase them.

The government has gradually changed tack since Peter Dutton became minister, and yesterday’s announcement makes it much clearer. But how much difference the new scheme will really make remains to be seen.

It is important to remember that the 457 visa was designed to bring in skilled workers. Of the 94,890 visa holders at 30 June last year, 55 per cent were in occupations judged as requiring the top level of skills, and 98 per cent were in the top three levels.

Yes, there are ridiculous examples of workers being brought in on 457 visas to do entry-level jobs. But the bigger danger is that it closes off avenues for young Australians to develop careers in occupations requiring skills: in restaurants, in IT, in management, even in medicine, where, as Mike Moynihan and Bob Birrell have pointed out, the open door to migrant doctors has added to a glut of GPs in the cities without providing more than a temporary respite for the shortage in country towns.

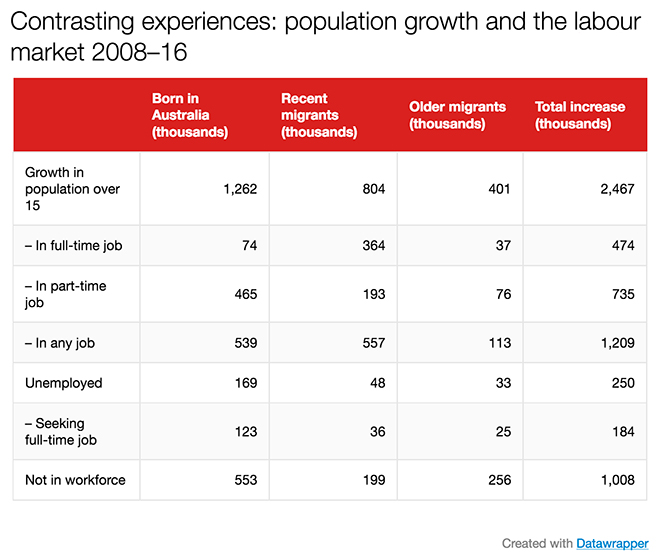

The table below, contrasting the experiences of recent migrants and the Australian-born, highlights our predicament. By making it so easy for employers to hire their skilled workforce overseas rather than face the expense of training Australians, we have closed off opportunities for young Australians to move up the ladder and gain the skills and experience that will allow them a good future.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Numbers rounded to nearest thousand or 1 per cent. Recent migrants defined as those who say they have been in Australia less than fifteen years, older migrants as those who say they have been here fifteen years or more.

Our future depends on Australians developing the skills to maintain a high-income, technologically advanced country in an increasingly competitive world. We made a mistake in following the US model of importing skilled labour and leaving the young in the rustbelt to scrape by as best they can. There are many reasons why our migrant workers are not generating enough demand to replace the jobs they have taken: what is clear is that our current system is not working for those who were born and raised here.

Fewer than one-in-six new full-time jobs, in net terms, now go to Australian-born workers. It’s not anti-migrant, let alone racist, to say that that is an outrageous failure of policy. May yesterday’s announcement be the first step towards putting it right. •