I didn’t really know what I was looking for, but with me that’s usually how these things begin. I was at the National Library of Australia in Canberra and in front of me were the two volumes of Manning Clark’s Select Documents in Australian History, published in 1950 and 1955. Turning the pages, I was thinking how groundbreaking they were in their day for having brought historical documents to the attention of a general reader. Today I suppose they are little more than historiographical curiosities.

Then I noticed a remark in Clark’s introduction to the first volume. He had focused mostly on printed sources, he explained, because unpublished documents were housed in such diverse places as to be “almost inaccessible,” and the task of finding material was so mysterious and exhausting “that only zealots sustain the quest.”

Odd thing to say, I thought, for a historian. I picked up the second volume to learn if he had elaborated on that. He had. In some quarters, he writes, there is a tendency to treat manuscript material “with reverence and awe — as though it had in some mysterious way the keys to great truths.” He had been “nauseated,” he went on, by this “cult.”

For his selection of documents Clark had found most of what he needed in printed primary sources such as government gazettes, parliamentary papers, newspapers, memoirs and so on, not original manuscript material. In that way, he went on, a researcher could follow up a point and not bump up against the rites of “the manuscript mystery cult” and find they had not the qualifications to be “initiated” into it.

I closed the books and put them on the returns trolley. Fair point about allowing others to follow up with the same records. And yet: cult? What cult? Practised by whom? Clark is famous for gnomic utterances like this, but still, what on earth was he talking about? Nausea? This is strong language even for him.

There’ll be an answer, I thought, as I moseyed upstairs to the main reading room. With Clark everything is personal, so it’s a safe assumption that there was someone, some despised colleague or colleagues, whom he couldn’t resist taking a swipe at in print. Twice.

I was diverted from this mystery by my next library task. I had called up two microfilm reels of the fortnightly newspaper Nation, published in Sydney between 1958 and 1972 and now it was time to read them. It’s been a long time since I’ve had to look at undigitised newspapers and I was half-expecting to find myself back in one of those big old newspaper rooms I remember from my student days.

If you were serious about researching Australian history back when the microfilm reader was king, these hot, noisy rooms and their quease-making machines were unavoidable. Something would always go wrong. You’d work up a temper trying to thread the film. You could never find the right-sized lens. There would not be enough machines that could also print. Or if you found one, it would have broken down.

Oh happy day when someone found a way to instantly produce a digital image from microfilm. Now, you sit in front of a computer with a microfilm spool attached, and although you still have to thread the film on to it, after that the hard work is done. You use the mouse to advance the reel to the dates you want, manipulate the images to your liking, then save them to a USB or send them to the printer across the room. Done.

Of course, you can’t search digitally — it’s still just microfilm — but from a secondary source I knew the date I wanted, 15 December 1962. On that day journalist Sylvia Lawson had published in Nation a piece called “Down to Journalism: The Self-Assessment of Mary Gilmore.” This is what I had come to see. For my own piece on Mary Gilmore earlier this year I had greatly enjoyed Lawson’s mini-biography of Gilmore, published by Oxford University Press in Australia in 1966. Only afterwards, darn it, had I learned that Lawson had previously written about Gilmore, in Nation.

Gilmore had died on 3 December 1962 aged ninety-seven, just twelve days before that piece appeared, and I assumed Nation had asked Lawson, a regular contributor, for an obituary. This is not a standard obituary but it does read as if the author assumed Gilmore would never see it. Lawson argues that Gilmore was a fine poet but it was her journalism that “expressed the whole Mary Gilmore.” It was a bold line to take because by then Gilmore was best known for her poetry and her two books of prose reminiscences. Her twenty-three years as a reforming journalist for the Worker would already have been a distant memory.

Lawson evokes what was going on in Gilmore’s mind and heart during the difficult years she spent living with her husband and small son on a property near Casterton in western Victoria. Despite her marital happiness, Gilmore felt lonely at Casterton until she was rescued by A.G. Stephens, editor of the Bulletin’s Red Page, who in 1903 began publishing her poems. This little bit of literary success, and her correspondence with Stephens (which Lawson quotes at length), meant everything to Gilmore then. “Country life is sweet and peaceful but there are times when the strenuous soul cries out for something more…”

“Something more” finally arrived in 1908 when, still living in Casterton, Gilmore was invited to edit the women’s page of the trade union paper the Worker. Then, writes Lawson, “the journalist… swallowed the housewife in one hungry snap.”

Very good. What captured my interest was that Lawson had obviously seen Gilmore’s original letters. She even notes an emendation made by hand in an otherwise typed letter. Where had she seen them? At the Mitchell Library in Sydney. In 1961, near the end of her long life, Gilmore had transferred great tranches of her papers to the Mitchell. A grandniece worked there and helped Gilmore sort and pack. Some books and papers also went to the National Library. (I discovered all this from W.H. Wilde’s 1988 biography of Gilmore.)

So, in 1962, Sylvia Lawson had gathered pencil and notebook, left her children to be minded by someone else, and taken herself to the Mitchell. There she must also have read the yellowed pages of the Worker in the original. No wretched microfilm for her. All of this must have been a tremendous slog; days of work. Sylvia Lawson, it turns out, was one of Manning Clark’s despised zealots of the reading room. She was not (at that time) an academic, but she obviously managed to initiate herself into the “cult.”

I returned the microfilm reels to the librarian at the desk feeling that my time had not been wasted. I’d learned why, when she returned to the subject of Mary Gilmore for OUP in 1966, Lawson had dedicated most of her thirty allocated pages (all titles in the series were strictly thirty pages) to Gilmore’s early life and her journalism for the Worker. Gilmore’s post-Worker years, during which she transcended writer status to become a much–loved celebrity, Lawson dismisses in little over four pages.

Of course her problem had been how to compress such a long life into a short space with so much manuscript material to draw on. I think it possible that Lawson only gained access to a small cache of Gilmore’s early papers and otherwise had to rely on published material. The result was unbalanced but nonetheless enough to satisfy her editor at OUP, who would have been expecting a fresh interpretation of Gilmore’s life, not a rehash of received ideas and standard opinions.

And this was why I was spending those Saturday mornings footling about at the National Library. In tidying up my own research on Gilmore I’d happened to glance again at the back cover of Lawson’s booklet and noticed that it was part of a series of mini-biographies published in the 1960s and early 1970s by OUP in Australia. I’d never seen them before or heard anyone mention them, and yet here was a long list of titles, many written by significant authors. By my count, OUP eventually produced sixty-three titles in the series. All are uniform in length, design and layout.

Here was I, then, on my own library quest, wanting to learn more about this small but interesting moment in Australian publishing history. Especially intriguing, the Australian Dictionary of Biography was establishing itself at exactly the same time, based at Australian National University in Canberra, with Melbourne University Press as publisher. OUP’s project was a minnow compared to the ADB, but nevertheless for twelve years, from 1962 to 1974, the Great Australians series swam successfully alongside the big fish that was the ADB.

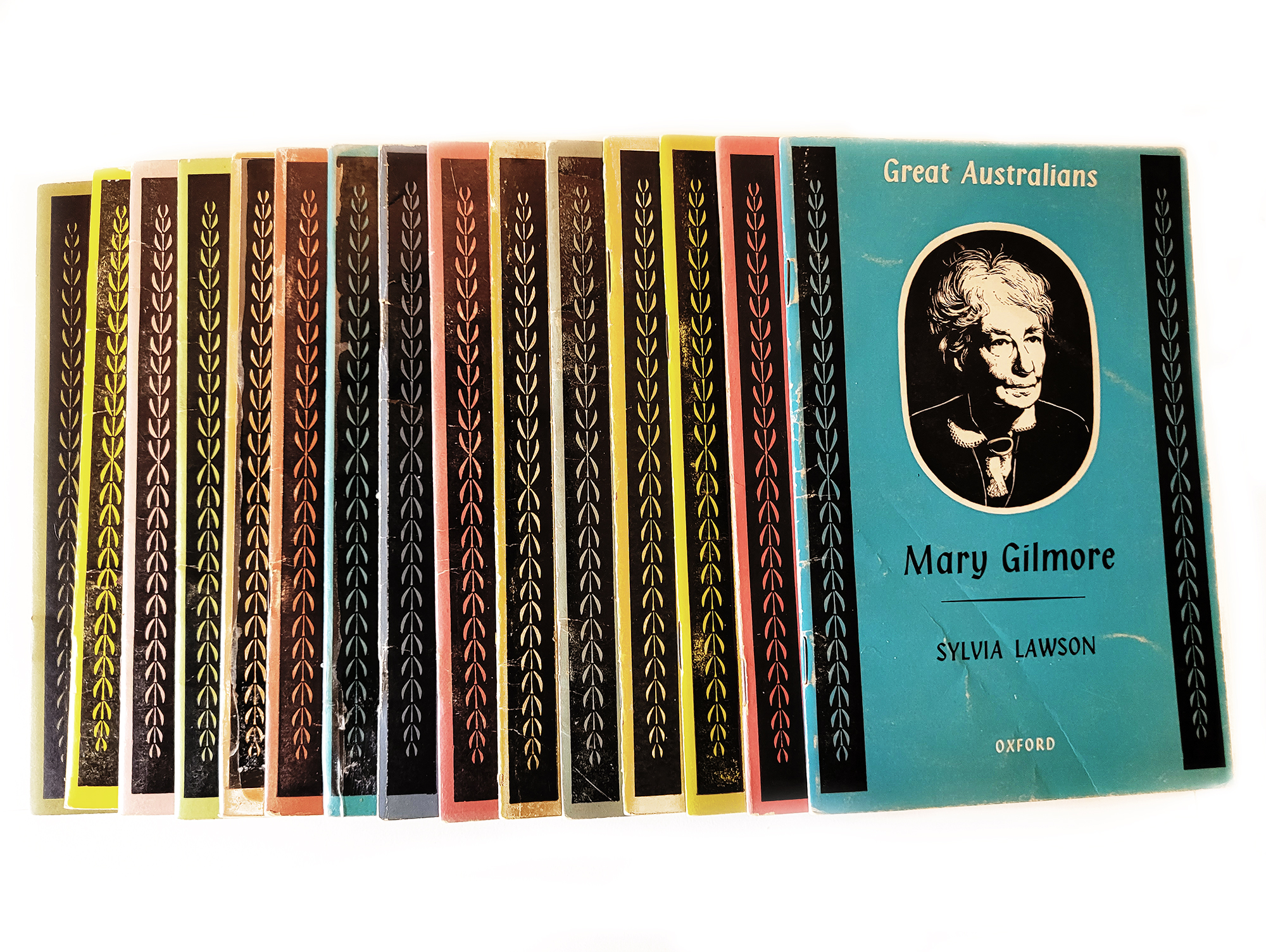

Mary Gilmore and fourteen of her companions in Oxford’s Great Australians series.

Englishman Frank Eyre had been appointed general manager of OUP Australia in 1951 and became a leading figure in the Australian book trade. His papers are held at the National Library so I thought I’d begin by looking there for anything on the Great Australians series. No luck. Odds and sods, nothing especially useful, or not for my line of enquiry anyway.

I turned instead to a history of OUP’s Australian branch that Eyre published — with OUP of course — in 1978. There he describes himself as a “practical idealist of the most incorrigible kind,” full of “determined ideas” for OUP and “relentless in pursuit of them.” To develop OUP’s Australian history list, he relied heavily on his colleague, David Elder, who was an acknowledged expert in history and much later contributed three entries of his own to the ADB. (Charmingly, one of these was on Frank Eyre, his own boss.)

This was when emergent Australian nationalism was driving huge interest in books about Australian history, culture and landscape. To meet the demand, new publishing houses — Jacaranda, Lansdowne and Sun Books, for example — were jostling with established firms such as MUP and Angus & Robertson. OUP was at the more conservative end, but still very interested in Australian themes.

Eyre had identified the impoverished state (his words) of scholarly writing on Australian history at the time and set about tackling it. In 1958 he published Russel Ward’s The Australian Legend, and in 1959 Judith Wright’s The Generations of Men. Both were enormously successful. Years later in an interview with the Age (I found a clipping of it in Eyre’s papers) Eyre claimed with obvious glee that eleven publishers had turned down Wright’s book before he took it, and by then, 1975, 100,000 copies had sold.

In 1955 Eyre asked Geoffrey Blainey, flushed with the early success of his book The Peaks of Lyell for MUP, to consider writing a short history of Australia for the general reader. Back in 1916 OUP had published Ernest Scott’s A Short History of Australia and had reprinted it many times, but it was out of date. When Blainey saw the sales figures and the royalties still being paid to the estate of the long-deceased author, he was tempted. But he turned the offer down.

Biography was the other opportunity spotted by Eyre. He can’t have been unaware of the ADB as an ambitious multi-volume biographical project aimed at academic and general readers, but he and David Elder were interested in a different sector of the market. Their Great Australians series was to be for secondary students. Eyre specialised in educational publishing and children’s books, so this was a natural direction for OUP to take.

However, as Eyre recalled, it was one of his first and lasting surprises that virtually every one of his titles would have to be written from primary sources. There were inconveniently few scholarly works for his authors to draw upon. Looming large in his mind was the experience of Kathleen Fitzpatrick, who in 1949 had published with MUP her influential book, Sir John Franklin in Tasmania. Expecting merely to consult the “recognised authorities,” she’d discovered that there were none. Instead, she’d had to seek archival records in Melbourne, Sydney, Hobart and Cambridge (her trip there was financed by her wealthy father).

First, though, Eyre and Elder made some key decisions about the design of their little books, because if they were to appeal to secondary students, they would have to look good. Book designer Alison Forbes was appointed to the task. Forbes had studied illustration and design at the Melbourne Technical School (now RMIT University), and a talk given there by Frank Eyre inspired her to specialise in book design. After graduating, Forbes spent several formative years as an illustrator with the Melbourne Herald. In 1956 she gained a steady job three days a week with MUP while also freelancing.

By my rough calculation each of the thirty-page stapled booklets carries about 9000 words and six to eight illustrations. The basic cover design and internal layout is unvaried across all titles, but each features its own illustration of the subject, drawn by Forbes, based on an archivally sourced photograph or drawing. The front and back covers are embellished with vertical bands of leaves. The process saw Forbes producing sixty-three original illustrations and identifying a unique colour for each cover. Happily, she is acknowledged in each booklet (although the editor of the text, never).

There must have been countless editorial meetings at OUP’s offices in South Melbourne in which Eyre and his colleagues thrashed out the matching of author with subject. I would pay for a fly-on-the-wall ticket to that. Could Dr So-and-So write about So-and-So, or were they already committed to the ADB? Could they stick to the word limit? Could they deliver on time?

Hold on, a telegram is just in from Professor Brainiac at Sandstone University: he is insisting he is the best author to write on So-and-So because he is already 100,000 words into a biography of So-and-So. But can Professor Brainiac deliver 9,000 words in six months? The alternative is to commission the professor’s sworn enemy, a certain Mr Packet-a-Day, who is a features writer for the Daily Bugle. Should we do that? An uneasy silence descends while everyone remembers what happened the last time Professor Brainiac and Mr Packet-a-Day crossed paths.

OUP could tempt its authors with money whereas ADB authors were unpaid. But a typical ADB author was an academic and the time-consuming primary research would be covered by their university salary. Furthermore, OUP was entirely constrained in its choice of subjects by what it thought would sell, whereas the ADB’s work was essentially underwritten by the ANU so it could afford to be bold in its choice and range of subjects. From its inception, as Melanie Nolan has noted, the ADB was committed to representing “all strands” of Australian life, including representative of types: a shearer, a drover, a rabbiter, a barmaid, a landlady.

Not so OUP. Its line-up of “great” Australians is a rather predicable group of governors, politicians, scientists, industrialists, entrepreneurs, merchants, artists and writers. Sometimes the author was almost as notable as the subject. Geographer Thomas Griffith Taylor wrote on Douglas Mawson. Nature writer Alec Chisolm on Ferdinand von Mueller. Novelist Ivan Southall on Lawrence Hargrave. Future governor-general Zelman Cowen on past governor-general Isaac Isaacs. (Manning Clark didn’t write for OUP’s Great Australians but in 1959 had contributed a booklet on Abel Tasman to an earlier short-lived series, a warm-up effort, dedicated solely to explorers.)

Some authors wrote on the same subject for OUP and the ADB: journalist Frederick Howard on Charles Kingsford Smith for instance, and historian Allan Martin on Henry Parkes. Probably there was a little jostling for the best authors but the ADB can’t have regarded OUP as a real rival and in that spirit, its general editor Douglas Pike, wrote for OUP on Charles Hawker and MUP publisher Peter Ryan wrote on Redmond Barry.

Of OUP’s sixty-three Great Australians only two were soldiers: John Monash and Thomas Blamey (both covered by historian John Hetherington). This may reflect a decline in interest in Australian military history in the 1960s. Less easy to explain is the absence of clerics: there are only three out of sixty-three. No sportspeople were included at all.

Such was the state of Australian women’s history at that time that only five women were covered: Nellie Melba, Caroline Chisolm, Henry Handel Richardson, Mary Gilmore and Catherine Helen Spence. Again, these were predictable choices, although it’s a surprise not to see Miles Franklin. More promising was the number of female authors in the series: sixteen women wrote on nineteen subjects. One of these was Edmund Barton, by Martha Rutledge, which was published in 1974 as one of the last of the series. By then Rutledge had begun a long association with the ADB and became one of its most prolific authors.

If the selection of subjects was unremarkable, what distinguishes the series was its fidelity to archives and its high publication standards. A secondary or university student who got their hands on any of OUP’s Great Australians was guaranteed no small thing: freshly researched history by some of the country’s finest writers and historians. And yet it is possible that with its emphasis on elites, the series actually prolonged the invisibility of First Nations histories and the lives of women and people from minority and neglected groups.

I drove back from the library that day thinking again about who Manning Clark might have been aiming at with his remarks about archival zealots. Was it Ernest Scott, professor of history and Clark’s lecturer at the University of Melbourne in 1936? At home I pulled off the shelves my copies of the writings of various historians recalling Scott’s legacy and yes, Scott’s dedication to primary sources was legendary.

In Clark’s 1990 memoir The Quest for Grace he damned Scott as a member of Melbourne’s “Protestant ascendancy” and chose to recount little more than Scott’s eccentric mannerisms during his lectures, entertaining and well-structured though these lectures were. His friend Kathleen Fitzpatrick, also one of Scott’s students, loved and never forgot Scott’s brilliant weaving of archival sources into his lectures, but this appears not to have impressed Clark.

Clark’s pronouncements on archives were deeply silly, of course. All around him historians were delving into original manuscript material and government records. A glance at the footnotes in the later volumes of Clark’s history of Australia shows he also drew increasingly on archives himself, but he had research assistants, archivists (and on occasion his wife Dymphna Clark) to do the initial harvest for him.

While they were eyes down on that, Clark went many times “almost as a pilgrim,” he says, to the entrance of Sydney Harbour at South Head. There he would “gaze over that vast sea” and try to think his way into the minds of those who had arrived there on ships. What, he would ask himself, did they do in the “ancient, barbaric continent” of Australia? For him, unlike the authors of those sixty-three little books, the answer did not lie in the reading room. •