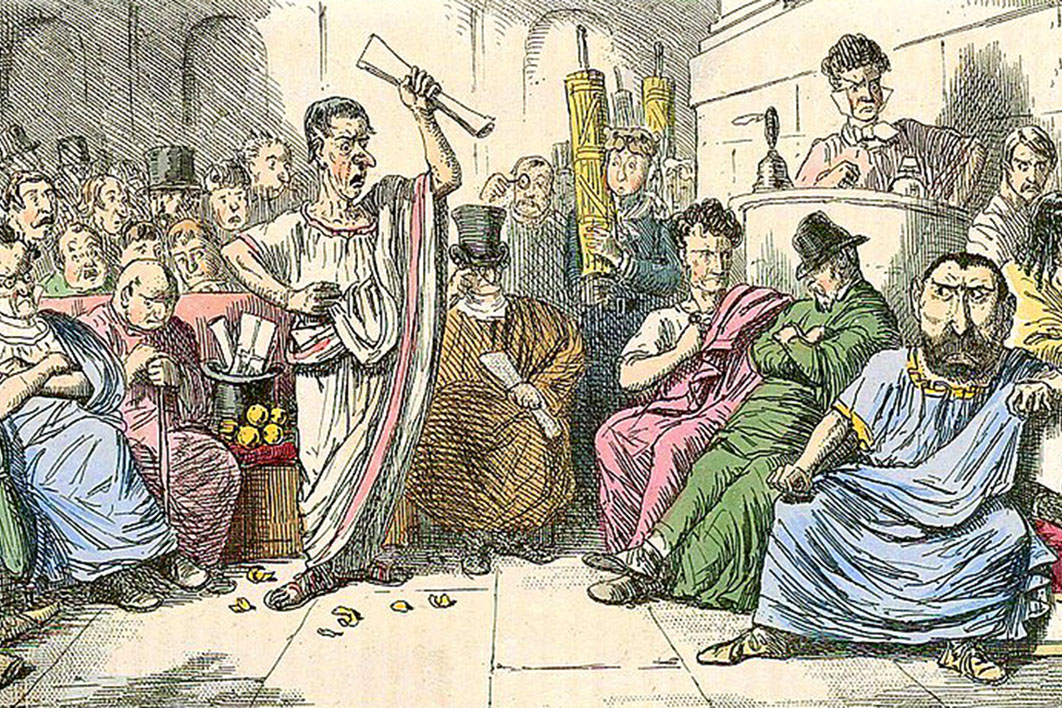

Early one morning in 64 BC a political candidate left his palatial home and set off through the streets of the most powerful city on earth to meet his destiny. The free-men of the Roman Republic were gathering on the Field of Mars to cast their vote for the man they wished to rule over them as Consul for the next year. And as he strode along, surrounded by his many supporters, the candidate might have muttered a simple mantra: “I am an outsider. I want to be Consul. This is Rome.”

The politician was Marcus Tullius Cicero, successful lawyer, Latin prose stylist, and Rome’s greatest orator; and the mantra came courtesy of his biggest supporter, his younger brother Quintus.

The Cicero Boys were intelligent, superbly well-educated and ambitious, but they weren’t aristocrats, they weren’t rich by Roman standards, and they had been born out in the sticks rather than in Rome. If they wanted power they were going to have to win it on the Field of Mars. To this end Quintus – who was effectively Cicero’s campaign manager – had written a long letter of political advice to his brother as his quest to become Consul began.

Recently published in a new translation by Philip Freeman as How to Win an Election, Quintus’s letter reads today as a clear-eyed essay on the cynical art of getting people to vote for you. Compared to the letters and speeches of his older brother, Quintus’s pamphlet is a minor work, but it is nevertheless fascinating because the ideas it extols and explains are just as relevant today as they would have been in ancient Rome. Empires may rise and fall, it seems, but human nature doesn’t change all that much.

Quintus starts off by telling his brother that getting elected is hard; every ballot is a mountain to climb. Acknowledge your weaknesses. Keep your eye on the prize. Leave nothing to chance. Quintus is reminding his more talented but more emotional sibling to stay focused, every day until election day. Quintus also warns Cicero not to rely too heavily on his natural talents. He might be able to sway a crowd with his oratory, but he also has to learn how to schmooze the punters one-on-one. Rule number one of getting elected, according to Quintus, is pretty simple: be disciplined enough to keep to all the other rules.

The other rules invoked by Quintus are just as basic – and just as hard to adhere to in the daily tumult that is politics.

Surround yourself with the right people. Pick advisers who will represent you as if they were trying to get elected themselves. Build a wide base of support. No matter how disagreeable you might find some of your supporters, hold your nose and count their votes. Promise everything to everyone. Deal with the problems that this will inevitably create after the election – when you have some power.

Rome, according to Quintus, was a “cesspool of humanity”; never assume too little gullibility on the part of the voters, or too little self-interest. Always exploit the weaknesses of your opponents. Never let a juicy rumour about your political enemies pass you by without passing it along. And don’t forget to flatter the voters – after all, they’re the real bosses, right? Yeah, right. Remember their names, give them your time. And at all costs give the electorate a sense of hope. The punters need a reason to vote for you, not just against your opponent. Oh, and finally, make sure you have the backing of those closest to you. As Quintus sagely warns, the nastiest stories about a candidate always originate from within his own camp.

And did it work? Of course it did. The rank outsider, the so-called “new man,” won handsomely. Cicero romped home against a couple of born-to-rule aristocrats who couldn’t be bothered to remember their supporters’ names.

Modern-day politics in Australia would look all too familiar to the Cicero Boys – in every respect except perhaps the role of the media. Though I’m sure the greatest orator of his day would have adapted rapidly, and easily come to dominate TV and radio in the same way he dominated the Forum, he never had to watch as his message was chopped into sound-bites by the six o’clock news.

And both brothers, I’m sure, would have seen a kindred spirit in opposition leader Tony Abbott. Under the rules laid down by Quintus Cicero over 2000 years ago, Abbott is running a highly effective campaign for office. He’s certainly been focused. Every day he finds a way of saying the same thing: the Gillard Labor government is a bad government. And he says it with conviction.

Abbott has also over-promised. He’ll bring in paid maternity leave and a budget surplus; he’ll turn back the boats; he’ll deal with climate change as well, but none of us will have to change our behaviour. He has leapt on Labor’s scandals with gusto. He has built his support among the mine-owning billionaires, and the refugee-fearing working classes. He has not given a sucker an even break. And every day he’s up at dawn to do it all again.

In the decades after Cicero’s consulship Rome descended into civil war and dictatorship, and despite his best efforts to save the republic from itself, the power of the ballot was soon cut down by the sword. In December 43 BC he was hunted down by the men of his enemy, Mark Antony. Reports say that his last words were, “There is nothing proper about what you are doing, soldier, but do try to kill me properly.” And with that he bared his neck and was promptly decapitated. Both Quintus and his son were also murdered in the round-up. The Cicero Boys – and the political machine they had built – were destroyed.

The head of Marcus Tullius Cicero was brought back to Rome and displayed in the Forum. As one last punishment it is said that Fulvia, Mark Antony’s wife, took down the head and plunged her hairpin through the great orator’s tongue.

Australia’s modern-day politicians will never be called on to show such courage in the face of their enemies. They have little to fear – except perhaps changes to their superannuation scheme. Both they and the voters should be thankful. •

How to Win an Election: An Ancient Guide for Modern Politicians

By Quintus Tullius Cicero | Translated by Philip Freeman | Princeton University Press | $30 | 128 pages