Last month in London, Michael Cooney, executive director of the Labor Party’s main think tank, the Chifley Research Centre, called for an end to what he termed “nostalgia for the new.” In a speech called “In the Shadow of Giants: the Paradox of Modernisation in the Second Generation,” he took particular aim at the obsession within his party with the Hawke and Keating governments of 1983–96, and the implication that this politically successful period can serve as a blueprint for Labor today.

Cooney characterised nostalgia for that period – the belief that if only the spirit of those times could be recaptured, all would be well – as a one-dimensional view of the recent past. Beginning and ending with “microeconomic reform,” this account was constructed by the party’s enemies, he argued, with the chief aim of flaying modern Labor. Yet it’s also something many in the party have internalised.

According to Cooney:

Parties which are homesick for the past, no matter how recent, and movements which long to debate the issues of fifteen or thirty years ago, can never effectively comprehend the real issues of our contemporary life.

Instead they fall into the trap of interpreting their own actions according to an “internal” frame of reference dominated by their own organisation’s experience of politics, rather than making their guide empathy for the people they are trying to serve and knowledge of the contemporary challenges of the nation they seek to lead.

Just as individuals who neurotically find validation by emulating their elders and finding increasingly remote and implausible analogies between their own approaches and those of very different predecessors in very different times can never expect to be taken seriously.

If you don’t ultimately trust yourself, how can you win the trust of anyone else?

On this point he is absolutely right. Trying to repeat the past is a recipe for dysfunction. Apart from anything else, any account of what happened is incomplete, selective or just plain wrong. History is often like that: the stories that develop through the years contain truths, yes, but also omissions, exaggerations and falsehoods. Random events sometimes alter the course of those tales, and as they are retold they are remoulded by ideological battles.

The Eureka Stockade is a good example of an account passed down from the generations that is claimed by both the “left” (as the first Australian revolt against the authority of a property-holding parliament) and the “right” (as an uprising of smallholders against oppressive government).

Glorifying the Hawke–Keating days is different because it is more recent, which means that today’s players tend to take its supposed lessons literally. But “be like Hawke and Keating” is about as useful as being exhorted to “be brave like the miners at Eureka.”

Bob Hawke and Paul Keating and their cabinets weren’t saints. They repeatedly said one thing before an election and did another afterwards. Keating and finance minister Peter Walsh referred to Hawke as “jellyback” because of his political timidity. The government’s model for electoral success largely depended on the opposition being even more gung-ho about dry economic prescriptions. And Keating’s surprise 1993 election win actually represented a blow against further economic liberalisation.

The bipartisan beatification of Hawke and Keating is relatively new. What the Coalition says about them now is not, of course, how it characterised them at the time. Back then, it was the familiar story: Labor was in the pockets of unions; it was captured by special interests; it was sending the country broke. For the first half of the Howard government from 1996, the most common reference to the Hawke–Keating legacy was the “Beazley black hole” and 17 per cent interest rates.

The most important lesson to take from these two alleged giants is that they didn’t yabber about the past, except to point out how much better their government was than the ones before them. That’s the kind of self-belief that has been normal for Australian governments, at least until recently.

Cooney’s comparison with individual behaviour is apt: people exhibit pathologies for deepseated reasons. But clinging to the recent past is not a cause of the party’s problems, it is a symptom. If a person spends much of their time longing for a happier, earlier time in their life that never really existed, and is prone to ingesting others’ views of their character, even an amateur psychologist would diagnosis underlying depression and low self-esteem.

Can something similar be said about an organisation? I think it can, and I also think Labor’s identity crisis predates the current 1980s retro-chic. Sometime after the 2001 election loss – the third in a row, but perhaps the most devastating because of the widespread expectation, until a few months before the poll, that a change of government was on its way – the federal party assumed a collective foetal position. It seemed to immerse itself in the opinion-page view of the political world and accept explanations hurled around about what was wrong with it.

Labor bought into the “Howard’s battlers” narrative (which is 95 per cent empirical nonsense), the need to “reconnect with the base,” and the party’s fatal estrangement from “middle Australia.” But most of all, Labor developed an infatuation with John Howard.

Labor fell for Howard hard, and accepted the idea that only a Howard could beat a Howard. This partly fuelled the preposterous elevation of Mark Latham to the leadership: he, like the prime minister, spoke the language of the suburbs.

Of course, existential angst tends to be the lot of major parties in opposition. When they move into government, they merge with the apparatus of state and any introspection becomes superfluous. They’re running the country, they’re where the action is, and that’s all that matters. The opposition persona is cast off, election promises are broken. The world throws up unexpected events and the government responds.

The Labor government of 2008–13 was different. In many ways it didn’t make the change from opposition to government. At first all seemed well, but perhaps six months into its first term the philosophical questions started creeping back. Who are we, what are we doing? Something was missing. Yes, Kevin Rudd’s character was a part of it, but in his inclination towards political shyness he was greatly encouraged by the party machine.

Then came Julia Gillard’s prime ministership, which in many ways represented an even greater capitulation to the rehearsed, clipboard-assembled, slogan-driven nostrums for political success. Who can forget “moving forward”?

A government attempting to relive a previous incarnation is bad enough, but an opposition doing that – as was urged on Labor during the last couple of terms of the Howard government and is again being urged today – is particularly bonkers. A party in government is one thing; an opposition is a different beast. Governments can do things, like Hawke and Keating did; oppositions can only talk.

If any elements of the Hawke–Keating years really have to be pored over by the current opposition, it’s how they came to office in March 1983. But even that’s not much use, because it’s impossible to know what really happened back then, and even if it were, the raw materials of that victory can’t be replicated.

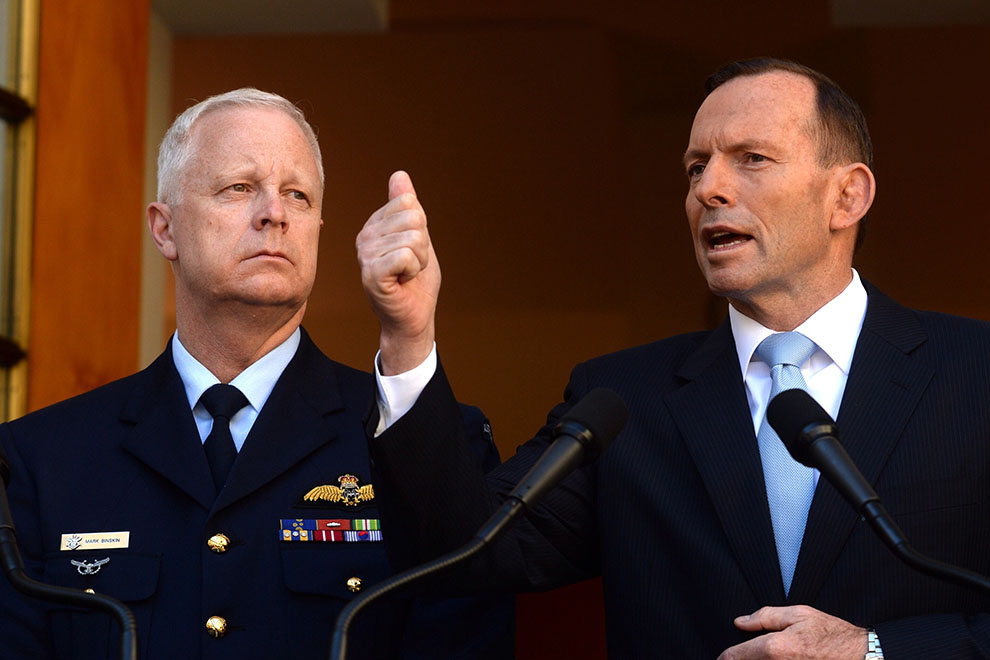

Now, it’s true that Tony Abbott talked a lot about the Howard government when he was opposition leader. But that was a conscious (and sound) political strategy, because the voters had warm memories of that recent period. To them it represented bountiful growth, open-wallet credit, budget surpluses and managerial competence. The Coalition’s message was that all it would take is a change of government for the good times to roll again.

It wasn’t true, of course, and since 7 September 2013 the story has changed: now, we’re in for a long haul. But more disturbing for the Coalition is a creeping tendency, in the face of stubbornly poor opinion polls, to succumb to that “nostalgia for the new” by aping what conventional wisdom regards as the basis of John Howard’s successs.

In my view, Howard’s longevity overwhelmingly reflected a booming economy. All the popular explanations at the time, about “values,” “battlers” and magnificent political skills, were really just fluff and entertainment. But the political class believed in them, and Abbott seems to believe too, if the signs that he is trying to generate a Howard “man of steel” persona are any guide: the over-milking of the Malaysian Airlines disaster in Ukraine, the unblinking wartime prime ministerial demeanour, and his deliberate and repeated use of Howard’s formulation that burqas or niqabs are “confronting.”

That tendency will be worth watching over the coming years. But it still has to be said that the current government, for all its faults, doesn’t lack self-belief. It doesn’t seem to doubt that it belongs on that side of the chamber.

There’s another way to characterise modern Labor, and that’s as a group of weak parliamentarians subservient to market researchers and machine men. Those “professionals” seem to believe politics is about asking voters what they want and then giving it to them. Their pearls of wisdom, strategically leaked, reflect too much time reading the opinion pages. Once upon a time they knew their place, and politicians (particularly politicians in government) let them know when they were getting beyond their station.

Cooney’s urging is easier said than done, because “nostalgia for the new” is a symptom rather than a cause. Federal Labor’s hollowing-out probably means it will take longer than it should, but the party will undoubtedly return to office one day. How it behaves when it once more controls the levers will indicate whether the current ailment is temporary or something more enduring. •