Mongolia’s position between two great powers, China and Russia, continues to shape its development in fundamental ways. Under Soviet Union domination until 1991, the country has undergone a political transition to parliamentary democracy. Yet this vast landlocked entity (it covers an area three times that of France) with huge mineral deposits is more dependent on the immense markets to its south, in China, rather than on sparsely populated Siberia, to the north, for its export sales. And the pattern of those sales sums up Mongolia’s predicament – it is hugely dependent on one country, with 90 per cent of its US$4.3 billion in 2013 export earnings coming from its southern neighbour.

Barely three million people fill Mongolia’s vast territory, and historically it has been claimed by both China and Russia. Russian influence during the Cold War was enormous, with the country’s leadership largely selected in Moscow. The country was a target of fierce rhetoric during the Cultural Revolution, with the radical leadership in Beijing claiming that it was encouraging separatists in Inner Mongolia, the autonomous region that was part of the People’s Republic.

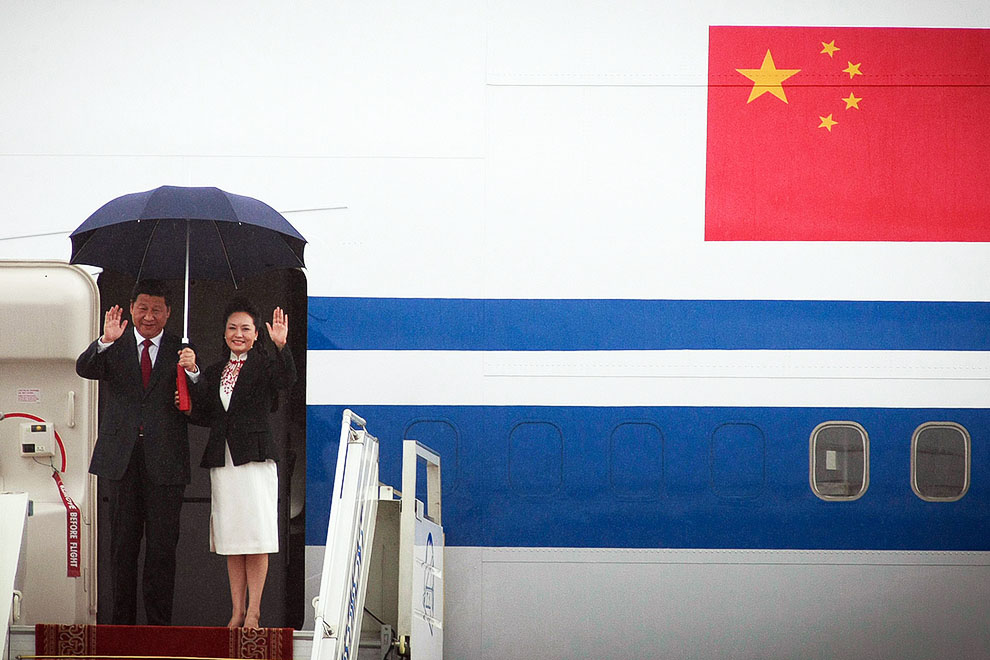

For a China always hunting for competitively priced resources to service its immense industrialisation process and developing internal market, Mongolia’s significance in the twenty-first century is easy to understand. A country just over the northern border with plentiful reserves of copper and coal is of immense strategic importance. Discussions about how best to service these needs were at the heart of President Xi Jinping’s visit to the capital, Ulan Bator, earlier this month. China agreed to help establish rail links and provide access to Chinese ports for Mongolian goods.

Despite the common economic interests, though, China has until now been surprisingly neglectful of its northern neighbour. This is the first visit by a Chinese head of state for over a decade. That neglect has contributed to Mongolia’s sense of vulnerability and pushed it into seeking other alliances. The new strategic partnership agreement with China, signed during Xi’s visit, comes only after security agreements Mongolia has struck with the United States and Russia.

Mongolia’s need to balance its two huge neighbours is neatly illustrated by the scheduled visit of the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, just a month after President Xi’s visit. Once again, the focus will be on creating the right infrastructure to exploit the country’s huge resources.

Mongolia is well aware that it is in a vulnerable position. While it has no practical alternative to dependency on the Chinese market, the urge to diversify is still strong. And having a relationship which balances Russia and China would suit Mongolia well, at least in terms of security. The signing of a LNG pipeline deal between Russia and China in May after many years of negotiations adds a new dimension. Both China and Russia have a mutual interest in a stable border across which the gas can flow, and a cooperative Mongolia is a vital element.

For Russia, irritated by Europe and the United States and feeling isolated by events in Ukraine, finding a new market for its plentiful energy resources was an urgent priority. For China, uneasy about its reliance on supply routes from an unstable Middle East largely controlled by the United States or its allies, the relatively free northern access routes has become more appealing. Complex and often fractious ties with Russia have given way to raw pragmatism; the two countries simply have to do business with each other, and Mongolia is sitting at the crossroads.

Whether Mongolia can avoid being overwhelmed by its two neighbours is unclear. It can’t become too close to either, and it needs to do everything to preserve its own sovereign identity. During President Xi’s visit the two countries committed to an extra US$5 billion in annual trade. But that deal might carry a hefty political price tag. China will expect diplomatic allegiance, and will certainly tie Mongolia closer to its own strategic interests. If it is to avoid the potential pitfalls of this relationship, Mongolia will need a supple and well-considered foreign policy. It has allowed foreign companies like the mining conglomerate Rio Tinto to operate mines in the country, but the degree of diversification is very limited.

All of this means that being part of a trilateral entity with Russia and China is reassuring for Mongolia, and creates the illusion, if not the reality, of economic and diplomatic diversity. It means that both Russia and China must commit to respecting the country as an partner, and must at least attempt to forge a framework for working together and a vision of shared security. This is fine as long as Russia and China sustain their current pragmatic relationship. Whether that will continue is a good question.

Xi Jinping made Russia his first destination after being appointed country president in 2013. In this he was emulating his predecessor Hu Jintao, who did a similar thing ten years earlier. Putin reciprocated with what was seen as a successful visit in May. At the moment, Russia is isolated and needs China more, perhaps, than China needs it. But these things can change quickly. It is quite possible that differences over the Middle East, for instance – until now, Russia has led the response on Syria at the United Nations, while China has followed – or other areas might cause the two to start drifting apart. In that scenario, Mongolia will be torn.

Mongolia occupies one of the toughest strategic positions of any country in the world. Sparsely populated, rich in resources, poor in infrastructure, and with countries to north and south that are far stronger than it is, it is truly forced to live on its wits. It is hardly helped by the very low profile that it enjoys ly. As many in its government have said over the last two decades, Mongolia is like the filling of a sandwich. The last thing it wants is to be devoured, which is why this new trilateral arrangement is so significant. Its most precious possession is its sovereignty; like any country, preserving that must be its main priority, even while it aims to optimise its economic opportunities. •