Narratives are how we make sense of our lives. Whether it’s an individual’s path from childhood to old age, or a nation’s transition through independence, changes of government and other events, narratives give shape to random events and mark out chronological structures that gain meaning over time. Making history meaningful is a major intellectual as well as political undertaking, and is highly contested in many cultures. Today, Japan’s historical narrative is shifting before our eyes.

Any nation is the subject of multiple narratives, but much of Japan’s twentieth-century history has been seen through one in particular: the path through war to peace. Japan’s rise as a military power, beginning in the 1890s, follows a narrative arc that is taught in textbooks and shown in television series, feature films and newspaper articles. With its several acts and dramatic climax, the story is well known to much of the audience.

It often goes like this. Fearful of Western expansionism, Japan fortifies itself with a modern military. Imperial Japan expands its borders to create a protective barrier; in the process, countless East Asian and Southeast Asian lives are sacrificed. The expansion begins to plateau as the Allies apply pressure during the second world war, and the dramatic climax is expressed through atomic bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki seventy years ago. The Japanese people are plunged into darkness and despair.

The occupation and reconstruction periods in Japan opened a new narrative. At the start of this story, Japan “forever renounce[d] war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling disputes,” in the words of article 9 of the national constitution. In essence, Japan’s Peace Constitution worked as a kind of plot device, transforming a tragedy into a new work in progress. This “master narrative,” arising from the highest legal document in the land, meant that Japan could redirect its history towards a new goal.

Decades later, Japan is known ly for its peace movement, which is nearly always connected to its anti-nuclear movements. Japanese peace activists have spoken powerfully at gatherings; Japanese atomic bomb survivors are closely involved in UN studies of disarmament and non-proliferation education. When UN secretary-general Ban Ki Moon visited Hiroshima on 6 August 2010 to participate in the sixty-fifth anniversary ceremony, the Japanese peace movement featured on an stage. In these and other events, Japan’s historical narrative has projected a future in which nuclear bombs or other weapons of mass destruction would never be used again.

But other narratives, of course, survived. Militarism could not be completely erased from Japanese society by the final defeat in August 1945, and it still lingers in the expression of military values in contemporary Japanese legal practices, in law enforcement, in the organisation of the Self-Defense Forces, and in the continuing revision of the militaristic narrative by historians and bureaucrats. The “history textbook wars” began in the 1950s, when the government and the teachers’ union squared off over who should write, and who should authorise educational materials. The Saburo Ienaga case, which spanned decades, was brought to court on claims that government censorship of passages dealing with wartime atrocities had infringed the author’s freedom of speech. In 2005, Nobel Prize–winning author Kenzaburo Oe faced a libel suit instigated by two war veterans who disputed his account of forced civilian suicides in Okinawa.

Japan’s peace narrative has not had an easy road, but its place in the constitution has guaranteed that it remains part of the national master narrative. Public support for article 9 was extremely high in the early postwar period, buoyed by a genuine sentiment for peace (and hatred of war) after the population’s direct experience of conflict. Over the years the Peace Constitution has been challenged by “interpretations,” such as those that allowed Japanese Self-Defense Forces troops to go to Cambodia as part of a UN peacekeeping mission in 1991, and to be deployed in Iraq in 2004–06 for “non-combat” tasks. These challenges were based on the argument that Japan should revise its constitution to pull it into line with other “normal” nations (meaning powers with large military forces). The claim is that Japan will never be treated as an equal on the stage until it abandons this provision. Fears of a strengthening Chinese army have further fuelled the desire for change.

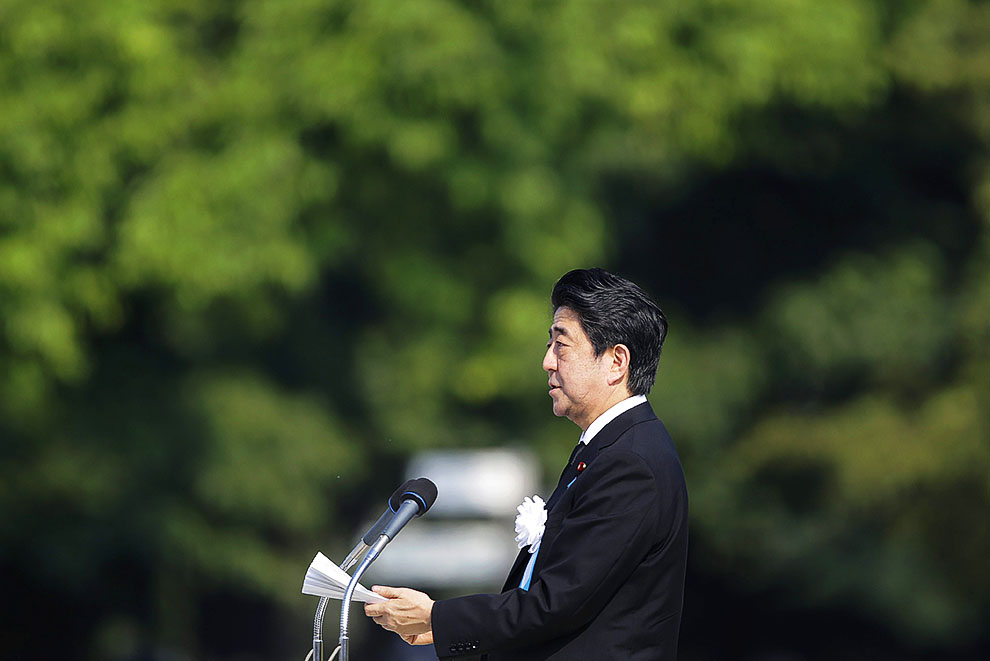

The narrative of normalisation squarely challenges the peace narrative. In July, the Abe government used its overwhelming majority in the Japanese parliament’s lower house to push through a new bill to expand Japan’s capacity in military action overseas, despite the fact that the majority of legal scholars polled said that the new law is unconstitutional. The bill, ironically called “The Legislation for Peace and Security,” will go to the upper house in the coming weeks.

While the Abe bill claims “collective defence” – attacks on allies would be considered the same as an attack on Japanese soil – as its main purpose, its most powerful effect would be to wind back article 9. But the bill has been so vaguely worded that few commentators have been able to unravel its real implications, and this will make it particularly easy for the Abe government (or future administrations) to make its own interpretation of the law.

The Abe government’s rewriting of the narrative of postwar Japan is often seen as a simple reflection of a new mood of nationalism in Japanese society. But there are good reasons to question that view. Fifty-nine per cent of the Japanese public do not support his military bill (and only 24 per cent support it). Even more strikingly, support for the existing Peace Constitution appears to be rising. While a Nikkei opinion poll of 2005 found a majority of respondents in favour of revising the constitution, an opinion poll taken by the Kyodo News Agency in July 2015 found 60 per cent in favour of retaining it as it stands. Of those who support the existing constitution today, 88 per cent cite the peace clause as one of its most valuable features. The Kyodo poll also revealed that a majority (52 per cent) believed Japan was heading in the wrong direction, with pessimism being highest among respondents in their twenties and thirties.

If “normalisation” becomes Japan’s new national narrative, it will undermine the hopeful story that has been told in classrooms and at rallies and memorial services since 1945. “Normalisation” strengthens the right-wing narrative that claims self-protection as a justification for expansion. All too easily, overseas military ventures could be justified as essential for deterrence and self-defence. Was not prewar Japan merely acting as a “normal” great power?

Many of us charged with writing and teaching the historical narratives of postwar Japan have recognised the power and logic of the peace narrative, and sought to refine and deepen it. The emerging narrative undermines core understandings, not just of the Japanese, but also of the Asia-Pacific and indeed of human history. We need to confront, debate and challenge its underlying assumptions. •