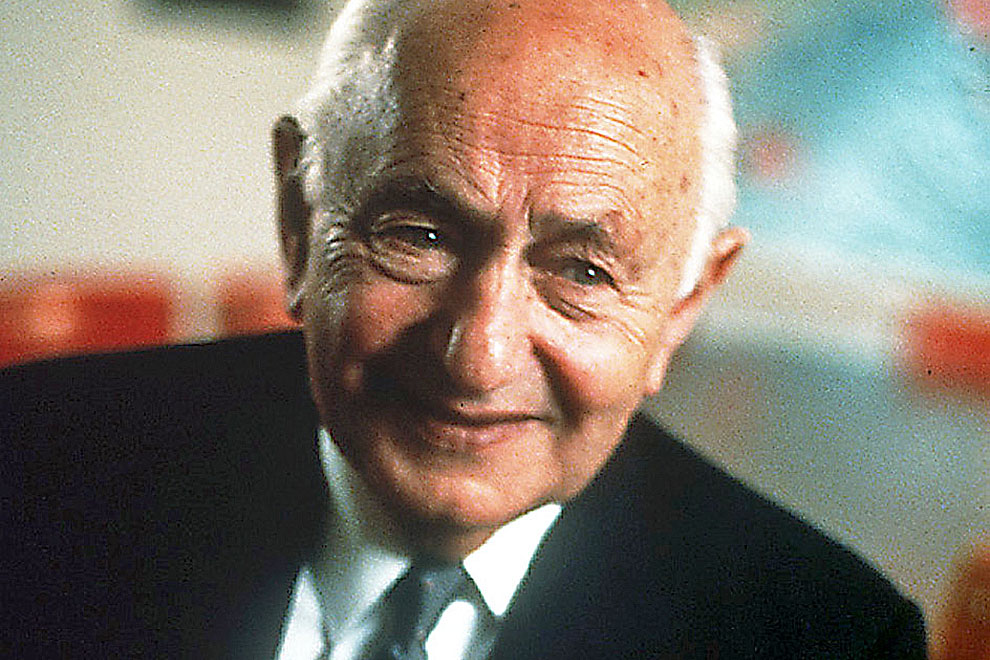

Santamaria: A Most Unusual Man

By Gerard Henderson | Miegunyah Press | $59.95

This biography of the energetic, influential and deeply divisive Catholic activist B.A. Santamaria has been eagerly awaited. Gerard Henderson joined Santamaria’s National Civic Council in the mid 1960s and worked for Santamaria himself in 1970–71 before eventually breaking with the organisation in the mid 1970s. He offers a valuable insider’s view of a complex man.

Henderson set himself a demanding task. Santamaria was politically active for over sixty years, and involved in many key social, political and religious debates. This is not a definitive biography; rather, it is an account of Santamaria through the eyes of a former colleague.

Henderson’s falling out with the man and the organisation came after Santamaria gave him most of his files on the Catholic Social Studies Movement – the forerunner of the National Civic Council – which played a key role in the 1955 Labor Party split. When Henderson wrote a more critical account than Santamaria expected, they parted ways, leaving a legacy of distrust and occasional exchanges in the media. Henderson then embarked on a career in conservative politics, working as chief of staff for John Howard in 1984–86 and later as a prominent media commentator, as well as setting up the Sydney Institute in 1989.

Historians have already covered much of the Santamaria story, as did Henderson in Mr Santamaria and the Bishops in 1982. This new book adds intriguing details and anecdotes, interviews with Santamaria’s colleagues and acquaintances (at least those who would agree to talk), and some recent research. It draws on Santamaria’s papers in the State Library of Victoria, but only up to 1975 because the Santamaria family has placed a forty-year embargo on the collection.

Henderson helpfully clarifies some matters, including Santamaria’s exemption from military service and some internal politics among Santamaria’s colleagues, notably the National Civic Council split in the 1980s. Chapters examine Santamaria’s relationship with the Democratic Labor Party, with the Australian Labor Party after 1972, and with prominent Liberal Party members, including Tony Abbott. Henderson also comments on aspects of Santamaria’s life, his religious (and football-related) convictions, memories of former colleagues, and his last years.

Henderson’s account is at its weakest when it discusses the contemporary debates about the role of the Catholic Church in politics, and particularly the importance of the leading French Catholic political activist Jacques Maritain (his name is consistently misspelt throughout the book), of whom Henderson is quite dismissive.

From the 1920s, Maritain tried to extricate the Church in France from manipulation by reactionary political movements, especially Action Française. He reworked Catholic political and social theory to focus on social justice, the defence of human rights and support for democracy.

The feature of Maritain’s thinking that most worried Santamaria was his attitude towards the Spanish Civil War. Maritain denounced what he called a “crusade mentality” that saw the war in quasi-Manichaean terms of good versus evil. As a leading member of the French Peace Committee he agitated for a negotiated end to that conflict, and wanted to remove its religious aspect entirely. But Santamaria and his patron, Archbishop Daniel Mannix of Melbourne, saw the conflict in terms of good versus evil, the Church versus communism.

Maritain’s political writing came down to this: the Church was entitled to address the moral implications of social and political issues in the public forum, but not to try to control democratic parties. Catholics were encouraged to take an active part in politics, but on their own initiative and responsibility, inspired by Catholic social principles but not under the direction of the Church unless vital Church interests were threatened.

This debate about the role of the Church in politics is central to any discussion of Santamaria’s role and influence. Henderson considers that Kevin T. Kelly, Xavier Connor and I – in my book Crusade or Conspiracy? Catholics and the Anti-Communist Struggle in Australia – are the “principal Catholic critics of Santamaria and the Movement’s involvement in politics.” All three of us, he says, “belonged to the Maritian [sic] Fan Club,” whereas Santamaria “showed little interest in theory” and, in 1953, “specifically rejected uncritical deference to Maritian’s [sic] authority.”

This was a bad mistake on Santamaria’s part. Had he been open to Maritain’s views, the whole sorry saga of the Labor split could have been avoided. Yet Santamaria and Mannix refused to listen.

Henderson dismisses Kelly and the Campion Society as ineffectual intellectuals. Yet the Campions were robust debaters, opening up to Australians the intellectual world of Catholic Europe and the United States. They not only promoted study programs and discussion groups in the Campion Society, they also wrote the Catholic Worker monthly for decades. Kelly expounded Maritain’s views, founded the first Young Christian Worker, or YCW, group in Melbourne, and promoted the concept around Australia.

The Campions had intended to found the Catholic Worker themselves, but while Kelly was on a trip to New Zealand Santamaria had jumped in and started it on his own. His impetuosity and lack of consultation annoyed the Campions, who sought to temper his enthusiasm and insisted on having some control. The paper, increasingly made up of Campion content, had achieved a circulation of 50,000 by October 1937.

Henderson has also misunderstood the significance of the YCW, which was inspired by Cardinal Joseph Cardijn in Belgium. Henderson says that it “focused on individuals, especially the task of bringing lapsed Catholic workers back to the Church.” The YCW, he goes on, was “all very theoretical, time-consuming and timid. Not the kind of involvement to excite Santamaria.” But Cardijn’s vision was far more robust than that. The YCW was for young people, many of whom left school early. At work, they could form small groups to discuss social issues and how to engage with those issues in the light of their Gospel discussions. They then determined on action.

Because Cardijn highlighted the crucial need for practical action, the YCW trained young people to engage in civil issues on their own initiative. It was anti-communist, of course, but it kept apart from party politics, and its leaders resisted efforts by Santamaria to conscript its members into his Movement.

The European political background to the Cardijn-inspired movements, and to the more controversial organisation, Catholic Action, is complex and varies between countries. Although this complexity helps explains some of the confusion about Catholic Action in Australia, Henderson doesn’t investigate the debates in Europe.

He claims that Pope Pius XII involved the Church in party politics when he endorsed the formation of the Civic Committees in Italy in 1948, fearing that the communists might win government. But the Civic Committees campaigned to encourage Catholics to vote in the election, not to interfere in party politics (as Santamaria sought to do). The role of the Civic Committees faded after the communist electoral defeat. Some members wanted the Church to play a more direct role in politics, but they were firmly opposed by the Christian Democrats, who were close to Maritain’s friend, Archbishop G.B. Montini, who would become Pope Paul VI in 1963.

Henderson is unsympathetic to one of Santamaria’s main antagonists, James Carroll. He argues that Carroll, Sydney’s coadjutor archbishop from 1954, illegitimately interfered in party politics by directing the Sydney Movement against Santamaria. But what was Carroll to do with an organisation ostensibly under the control of the bishops, as Santamaria had long contended, but which had dragged the Church into a bitter struggle for control of the Labor Party?

Carroll was trying to stop the Sydney Movement from being a pawn in Santamaria’s contest for political power. It was a real dilemma: if Carroll didn’t intervene, the Movement would have claimed the authority of the Church in Santamaria’s attempt to win influence in the Labor Party. The Sydney bishops supported the fight to defeat communist influence in the unions and elsewhere, but rejected Santamaria’s overreach for political power.

Henderson contests my view that there was a convention in Sydney against direct involvement in political parties. After Cardinal Moran’s time, though, the Sydney archbishops were very wary of political involvements, especially like those of Mannix in Melbourne. Sydney’s Archbishop Norman Gilroy remained in the devotional mould of Archbishop Michael Kelly, who died in 1940. After the sectarian outburst against the Catholic-based Democratic Party in 1920, the Sydney hierarchy was hardly likely to favour Santamaria’s political ventures.

Henderson also downplays the fact that the Movement claimed to act with the full authority of the bishops. As I documented in Crusade or Conspiracy?, Santamaria repeatedly invoked the authority of the bishops to demand obedience to his control. This was what the disagreement with the Campions and YCW leaders was fundamentally about. Only when the Movement began to fragment, along with the support of the bishops, did he reverse positions and claim that the Movement was always an independent organisation of laypeople.

Santamaria could have been the grandfather figure for the Catholic justice movements in Australia. Instead, he became a bitter enemy of the social justice currents inspired by the Vatican Council. He was what scholars call an “integralist,” an ultramontane who exaggerated the authority of the Church and the papacy (though only when they agreed with him). He insisted that his faith depended on preserving this authority, and considered Pope Paul VI’s 1968 decision against contraception as infallible. It will be up to later historians to investigate Santamaria’s campaign to save the Church, especially through his magazine, AD2000.

Much more needs to be done before we have a comprehensive biography of Santamaria. We lack analysis of Santamaria’s activities from the 1960s, including during the Vietnam war, when he strongly influenced Catholic opinion. Frank Mount has written of his work for Santamaria in the Pacific Institute, organising anti-communist networks throughout Southeast Asia, and Henderson writes that “Santamaria attended all the Pacific Institute’s conferences” from 1965 to 1975; yet this is a largely unknown story inviting further research.

Henderson judges that Santamaria was right in opposing communism but does not examine his exaggerated judgement about the degree of the threat, which distorted his perception so badly about conflicts in South Africa, Rhodesia, Indonesia, East Timor, the Philippines, South America and elsewhere.

Henderson’s skimpy account of the disputes over the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace, or CCJP, from 1972 depicts Santamaria reacting against “left-wing” laypeople making political statements in the name of the bishops. For Henderson, this was “yet another example of the inherent inconsistency of those who issue general warnings about the Church’s involvement in politics.”

Yet he ignores scholarship on this dispute, especially Therese Woolfe’s 1988 thesis, Witness and Teacher: the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace, 1968–1987. The CCJP’s activities differed greatly from Santamaria’s. It sought to educate Catholics about Church social principles and to suggest policy implications. Though they were approved by the bishops, CCJP statements did not bind under religious obligation; instead they were commended to the consciences of Catholics for serious consideration. The CCJP acted openly and was not secretly attempting to penetrate political parties.Henderson makes no mention of how, in the 1980s, Santamaria organised an extraordinary boycott of Project Compassion, the Church’s annual Lenten appeal to fund its aid organisation Australian Catholic Relief (later Caritas Australia). Santamaria alleged that Australian Catholic Relief money was going to communist groups in the Philippines and elsewhere, and many of his clerical supporters brought their parishes into the boycott, especially in Melbourne.

Henderson defends Santamaria’s notion of “permeation” in the Labor Party but ignores the fact that the secret Movement, operating clandestinely on the authoritarian model of a Leninist party, claimed to act in the name of the bishops and aimed to influence the Labor Party, if it won government, to implement Santamaria’s view of Catholic social thought.

For Henderson, Santamaria’s political agenda “is more properly read as an application for continued funding that exhibited a certain naivety about Australian politics.” It is hard to credit such a judgement. The substantial theoretical issues about the role of the Church in a modern democracy have almost entirely disappeared from his view.

Santamaria has no footnotes, but it does have an excellent index and extensive bibliography. •