AUSTRALIANS are famously inept at pronouncing foreign names, and wine nomenclature is no exception. A few years ago, when Yalumba made a big push to promote a new white wine variety with origins in the Rhône valley, large banner advertisements resorted to spelling out the French name in phonetics: VEE-ON-YEE-AY. Over the next few years, wine-drinking Australians will be mastering (or butchering) more of these alien grape names. Most will not be French, but Spanish and Italian. Some may be Greek.

An intelligent local interest in cultivating non-French Mediterranean varieties is overdue. James Busby and the Macarthurs of Camden, the great nineteenth-century cadgers of cuttings from the vine stocks of Europe, bypassed Italy entirely, possibly deterred by the teeming, chaotic nature of its vine ownership and production.

As the landscape of modern Australian winemaking developed, it remained almost bereft of Spanish and Italian vines, verdelho and the sherry cultivars being notable exceptions. Even that great lateral thinker, David Wynn, who snapped up the idea of Chianti’s oversize glass bottles as the inspiration for the Wynvale flagon, didn’t think to bring back cuttings of sangiovese. (He, like many subsequent critics, may have found basic Chianti too lean and acidic.)

Italian and Spanish grapes eventually began to make sporadic debuts from the 1970s onward. Mark Lloyd of Coriole finally gave sangiovese an Australian billet in McLaren Vale, while elsewhere interest grew in tempranillo, the chief variety of the noble reds of Rioja in northern Spain. Margaret River’s Cape Mentelle signed up inadvertently, their supposedly Californian grape zinfandel later turning out to be the ancient Italian cultivar primitivo. From the early 1990s, Victorian Garry Crittenden went for total immersion, devoting his entire operation to Italian grapes and putting the colours of the Italian tricolour on his label.

In the past decade, Australia’s vine quarantine system has been working overtime, with imports from Italy in particular looming large. Since its inception in 2001, the Australian Alternative Varieties Wine Show has been unearthing examples of new, or steadily improving, wines made from little-known varieties. This year, it produced a quintessentially obscure variety as its best in show, a white wine made from a grape cultivated by only one winemaker in Australia. Bianco d’allessano has its origins in the dusty southern Italian region of Puglia, and is made by Salena Estate in the troubled Murray-side vineyards of Loxton.

Max Allen, chief judge of the show and wine writer for the Australian and other publications, must be overjoyed. He has become the public face of the movement to adopt a wider range of varieties and styles in Australia. Apart from his desire to expose our palates to a novel range of flavours, he believes that cultivating varieties from Spain, Italy and Greece that are more simpatico to Australian conditions is a step towards sustainable, responsible winemaking, particularly as our climate warms.

Allen’s new book, The Future Makers, is both an exegesis and a celebration of his vision. He spelled out his hopes in a Business Wine Magazine article five years ago: “If we can find grapes that are drought tolerant, disease resistant, need less manipulation in the winery, and still taste great,” he wrote, “then surely everybody benefits.”

In The Future Makers, after setting up his stall with concise essays on terroir – the soil, topography and climate in which wines are grown – and the likely effects of global warming, Allen gives readers a useful rundown of the varieties on the up and up, from those that are now comparatively well entrenched – pinot gris and viognier, petit verdot, sangiovese and tempranillo – to newcomers that have only a toehold; whites that boast names such as malvasia istriana and vermentino, and reds called anglianico, negroamaro or schioppettino. Allen is elated by the possibilities, and what begins as a paean to the new wines mutates into a hymn of praise for their creators. Nearly all are small winemakers, many of whom have chosen to practise organic viticulture and winemaking.

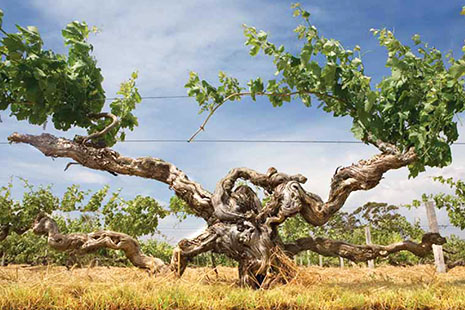

Organic winemaking has grown steadily in the last ten years, and now more than 600 winemakers follow intensive practices that rely on compost and manure to nourish the vines and regenerate the soil. They spurn the use of toxic sprays to kill weeds and insects. When used at all, irrigation is kept to a minimum, and additive chemicals are shunned in winemaking. Many of these vignerons are also moving to a more extreme and controversial form of organic farming – biodynamics.

If Allen seems to skate lightly over the lack of scientific credentials for biodynamics, he has little choice. The tenets of biodynamic farming sprang fully formed from the mind of Rudolf Steiner, with little empirical – let alone scientific – basis, as he himself admitted.

Steiner was an Austrian thinker, whose credo – anthroposophy – dwelt on forming closer connections between the physical and spiritual worlds. In a series of lectures in 1924, Steiner delivered his agricultural blueprint. Its focus was a series of elaborate preparations of natural materials, which are usually matured underground before being applied to compost, plants and soil, often in the form of a highly dilute spray. The timing of these procedures is linked to the lunar calendar and the movements of the planets.

Steiner is a soft target for sceptics. Many of his ideas and beliefs range from the eccentric to the plain loopy. His opinions on the origins of the human species, for example, rival L. Ron Hubbard’s for outlandishness. More relevant and cogent doubts about the value of biodynamic farming, however, come from trials by American universities, which show that biodynamic practices have no discernible difference in outcome from more conventional modes of organic farming.

In the absence of scientific bona fides, Allen opts for an accumulation of testimonials from the growing list of biodynamic practitioners. And it is an impressive roll call, including highly successful and respected vignerons such as Vanya Cullen and Prue Henschke. It also seems that biodynamic wines have powerful friends in the pre-eminent wine critics of the northern hemisphere, Robert Parker Jr and Jancis Robinson.

It is clear, though, that many of the exponents of biodynamics are partial converts who are picking and choosing from the biodynamic catalogue. How many, for instance, actually use Preparation 505, which calls for ground bark to be matured in a freshly killed cow’s skull?

The mood among Allen’s interviewees could be seen as a backlash against the scientific and technological rationalism that propelled the runaway growth of Australia’s now faltering wine industry. In Europe, the word “industrial” was always a snide descriptor, and the model of small-scale, organic, site-linked winemaking pursued by many contemporary French vigneron-winemakers is clearly gaining traction here.

In a column in the Times in 2008, the British wine writer Jane McQuitty accused Australians of being obsessed with fault-free winemaking to the detriment of flavour and complexity. Sandro Mosele, of Mornington Peninsula’s Kooyong winery, explicitly rejects the relentless pursuit of hygiene, telling Allen: “Australian wine makers have been concentrating for too long on making wine according to the twenty tenets of [Brian] Croser they learned at wine school. They’re obsessed with clean juice, using cultured yeasts, chasing varietal expression. I’m not… I want to make grapes that taste of the soil where they are grown.”

Ironically, Croser himself turns up in Allen’s book. The former proprietor of Petaluma, peripatetic consultant winemaker and pioneer of the Charles Sturt University oenology course, is now making small-scale batches of wines at different sites in South Australia.

IN A THIRTY-YEAR career, Adelaide wine journalist Philip White has earned a reputation for his trenchant opposition to what he calls the “mindless industrial monoculture” of bulk production by the major wine companies, and to the profligate waste of water that ensues. Informed by a background in geology, he is a constant advocate for the nuances of terroir and has long been urging a greater diversity in Australian cultivars.

Reviewing a meagre class of “Other red wines” in the Adelaide Advertiser’s Top 100 in 2004, he wrote: “If you realise that the corner deli drinks fridge contains a much wider array of flavours than the local wine shop, you could be forgiven for wondering why, of the thousands of grape varieties growing on this little planet, we’ve restricted ourselves to the few staples of Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne and the Rhône.” The prospects for imminent change? “Don’t hold your breath.”

White welcomes the gathering momentum – entries in the Alternative Varieties Wine Show almost reached 600 this year – and is all in favour of Max Allen’s role as spruiker. At the same time, he urges a degree of caution, citing the disastrous error of identity surrounding the Australian arrival of the prized white Spanish grape albarino. Instead of the flavoursome prestige variety they believed they had purchased from the CSIRO, DNA testing revealed in 2009 that several vignerons, principally the Barossa’s Damien Tscharke, were cultivating savagnin blanc, also known as the rather dreary grape traminer.

Even when a variety is bona fide, White says the results can be indifferent if the grape is not properly understood. As an example, he points out that many Australian growers of tempranillo hadn’t noticed that in its hot native locales, the best wines are grown at high altitudes, subjecting the fruit to savage swings in diurnal temperatures. White believes that more experimentation and more rigorous research by both vignerons and wine scientists are needed to get wines right before they are put on the market.

“Intellectual rigour is at least as important as passion,” says White. “We shouldn’t be paying $50 to drink people’s experiments.”

Despite Max Allen’s enthusiasm, the notion that small, sensitive winemakers have a mortgage on quality does not command universal acceptance: veteran wine judge and commentator James Halliday rejects the David and Goliath scenario, dismissing the “same old tired arguments that single vineyard wines are inherently more interesting, and of higher quality, than vineyard or regional blends.”

There is likely to be resistance in the market too. Even allowing for the strongish uptake of pinot grigio/gris and viognier, selling a plethora of new varieties and regions has its own difficulties, both domestically and overseas. In 2004, the then wine buyer for the British supermarket chain Tescos, Phil Reedman, warned Australia not to follow the French down the path to impenetrable complexity for the consumer.

Up to a point, Philip White agrees. “The punter has to accept it, and that hasn’t happened. The new wines, like gargenega and saperavi, are exciting and cool, but they are going to be really hard to sell. And who’s going to judge them at the wine shows, and say which is a good one?” •