I have on my wall at home a large drawing in charcoal and acrylic by the late Roy Jackson. I bought it from the artist thirty-three years ago and it never gets stale. But it divides people, women especially. The drawing is of a nude model, a Japanese woman, and some people see only violence when they look at it. There’s a frantic quality to the image, the model’s arms seeming to flail in self-defence.

I have never seen it that way because I know how the picture was made. Rather than flailing limbs, the artist’s subject was extreme calm. As he drew her, Jackson’s model was doing the one thing models aren’t supposed to do: she was moving. It was very slow, a sort of stop-frame tai chi, yet it was all Jackson could manage to keep up with her – every time he looked up, she was in a slightly different position. What I have hanging on my wall, then, is a very fast drawing of very slow motion.

Of course, those who see the image differently aren’t wrong. If art isn’t open to multiple interpretations, it probably isn’t much good. But sometimes we base our judgements on misinformation.

Not long ago, a colleague told me that the song “My Funny Valentine” was vile and sexist because the singer was telling a woman not to “change a hair” for him, and that it didn’t matter if her mouth was “a little weak” and she wasn’t all that smart. Well, fair enough, I suppose, if you’ve never listened to the verse of the song, only heard it sung by a man and don’t know its context. In the 1937 musical comedy Babes in Arms, for which Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart wrote it, “My Funny Valentine” is sung by a woman to a man named Valentine. Sometimes a small piece of information makes a big difference.

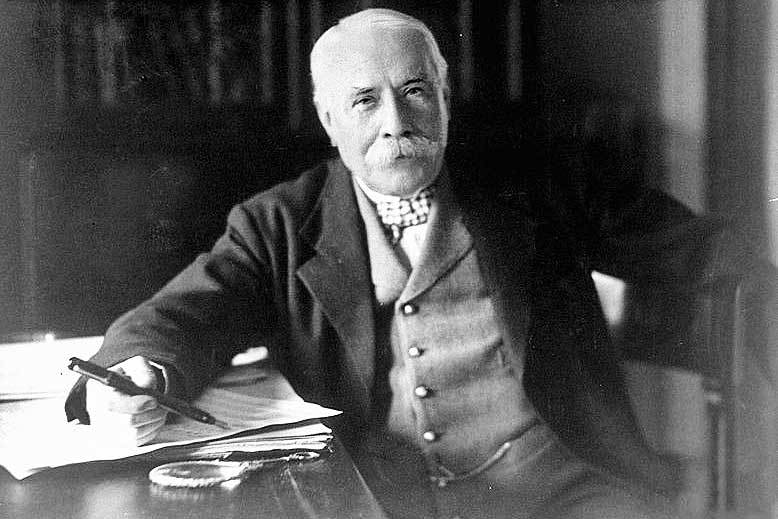

But it’s also true, and no less so for being a cliché, that a little knowledge is potentially dangerous. Certainly when it comes to the music of Edward Elgar, what people think they know about the composer can lead them to miss the power of his music completely. I was once told by a friend that Elgar’s first symphony made him feel ill. He resented the music for its supposed celebration of the British Empire. It was something to do with the flag-waving of the Last Night of the Proms and the words fitted to the trio of the first Pomp and Circumstance march; also, stiff upper lips. I suppose there must be people who like Elgar for the same reason. But they’re all wrong about the composer.

The words to “Land of Hope and Glory” are not Elgar’s – he rather disapproved of them – and far from being an establishment toff, Elgar had a provincial, middle-class, Catholic upbringing that branded him an outsider. He felt it, too, all his life. As for the stiff upper lip, you only have to listen to Elgar’s own recordings to hear this music played with fire, passion and generally swift tempos.

But what about the Englishness of it all? I think that bothered my friend as much as anything. I’m afraid I don’t hear it, and I’m not sure what it is that others hear. There’s certainly no English folk music pervading Elgar’s work, as there is with Vaughan Williams (Elgar thought composers who used folk songs were being lazy). In fact, Elgar is as European as they come. His tunes often hint at Chopin, his brilliantly skilled orchestration owes something to Mendelssohn and Berlioz, and there’s frequently a rhythmic spring that comes from Schumann – the Schumann of the Rhenish symphony surely lies behind the opening of Elgar’s second. He is, perhaps above all, the great synthesiser of those apparent opposites, Brahms and Wagner. And when Richard Strauss, Elgar’s slightly younger contemporary, first heard The Dream of Gerontius (itself unthinkable without the example of Wagner’s Parsifal), he toasted him in broken English, calling him a “progressivist.”

The supposed Englishness of Elgar’s music is also the reason it is supposed not to travel well, though he was quite an international figure in his lifetime. The first symphony was played all over Europe and the United States, a hundred times in its first year; Yale gave the composer a doctorate; Mahler conducted the Enigma variations. But that imperialist reputation has dogged Elgar’s music since his death (in 1934), and today it is mostly English-speaking countries that play his work. So it is particularly good to hear recent recordings of Elgar’s symphonies played by one of Europe’s oldest orchestras and one of its most distinctive, the Berlin Staatskapelle under Daniel Barenboim – an Argentinian-born citizen of Israel and Palestine, but a lifelong Elgarian.

When it comes to the quality of their sound, so many modern orchestras offer the same “international cuisine,” but the Staatskapelle does not. Above all, its strings produce a sinewy texture, a mellowness of tone and remarkably well-articulated phrasing. They etch and dig. These are inadequate words – trying to describe the sound of an orchestra is like trying to describe wine – but suffice to say the recordings have reminded me, once again, of the central European roots of England’s most famous composer, and of the emotional power of his music. •