“A poem is never finished; it is only abandoned,” wrote W.H. Auden in the preface to his Collected Shorter Poems in 1966, and proceeded to abandon – in another sense – not only some of his own lines but also whole poems. Auden explained that besides fixing up his earlier “slovenly” writing, he was also leaving out poems he now considered dishonest. These included the famous “September 1, 1939.”

Auden was paraphrasing an observation by the poet and purveyor of aphorisms Paul Valéry. The Frenchman had been more precise, explaining that “a work is never completed except by some accident such as weariness, satisfaction, the need to deliver, or death.” Of these four states, “satisfaction” is the only one that wears off, as Valéry’s compatriot and contemporary, the post-impressionist painter Pierre Bonnard, knew well. Even when one of his paintings was hanging in a public collection, Bonnard was known to whip out his oils and touch up a detail that no longer satisfied him.

In 2007, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra gave the first performances of my short piece Headlong, a work it had commissioned as part of its seventy-fifth birthday celebrations. Jeffrey Tate was the excellent conductor and he drew a particularly fine, clear, even passionate performance from the orchestra. The piece was meant to be a celebration, but something seemed wrong.

Headlong was a piece with a plan. Its structure involved a seventy-five note melodic line – a tone row – that shot around the orchestra, its rhythm always fluctuating, leaving its harmony in its wake. The row repeats a semitone higher, then a semitone higher, then a semitone higher, until finally it runs smack into a suitably jubilant chord of A major. It was a display piece for the orchestra – everyone gets a little solo – and bar for bar, the music sounded fine. But the ending appeared to come from nowhere.

Apart from devising my long tone row, the only thing I’d decided in advance was that it would be unstoppable; this line would rush through the piece – headlong – from start to finish, now in one octave now in another, now in the violins, now on the tuba, slowing in the middle of the piece, but never stopping. Yet that final chord never felt earned; the arrival at A major lacked inevitability, even if my long and winding row insisted that it was inevitable.

At the end of the first performance, I thanked the conductor and asked if the following night he might bring himself to play the central section a little more slowly; after the second performance, I asked him to play it more slowly still; finally, following the third performance, I asked him to slow the whole piece down. Sir Jeffrey is a lovely man and did as I asked. I have a CD of all four performances, each longer than the last. Headlong wasn’t a disaster – the ABC sent the final performance to the European Broadcasting Union and, for the next few years, radio royalties trickled in from all over Europe – but I still wasn’t satisfied. When the SSO informed me it would be playing the piece again in the 2017 season, I decided it was time to pull it apart and fix it.

There is nothing wrong with using a system. It functions like a clamp on some aspect of the music, usually rhythm or, as in this case, pitch. Composers have been doing it since the Middle Ages, and there can be something powerful in a work of art that contains fixed elements (my tone row) alongside free elements (everything else in the piece). But sometimes, a system can lead you into trouble, because having established the rules of the game you tend to follow them. The tone row in Headlong ran through the piece without stopping. That was the point of it. But it ought to have stopped. The listeners – I include myself – needed more time to take in all that information, and slowing the music down wasn’t enough.

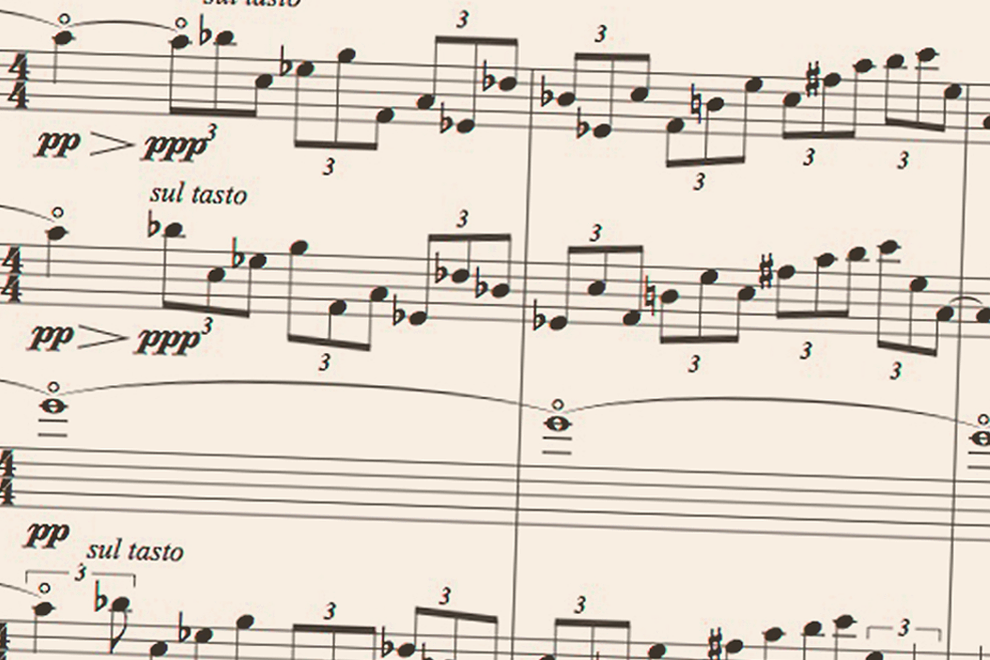

So I cut a hole in the music just after it reaches the central section. There’s a silence, a moment to breathe and reflect on the story so far. After the music picks up and carries on, there are numerous places where a note is held longer, a couple of bars are inserted to draw out a harmony, a rhythmic figure extended. I felt the piece was a tight-fitting garment that I was letting out. In the process, of course, I was breaking my own rules. There were now places where the line of notes didn’t move forward, but lingered or doubled back on itself. Well, they were only my rules.

So is Headlong now finished or merely abandoned again? One of the changes I made to the score when I revised it was to add a new last bar. It didn’t replace the old last bar, but was in addition to it. A second thought, an esprit d’escalier. The final peroration happens as before, though at slightly greater length and leading more purposefully to the A major chord. But where once a big fat pause sat on that chord, now it is played in strict tempo, followed by a sharp attack on the same chord, then a (sort of) F sharp minor eleventh chord (in case you’re interested) that splinters apart as individual woodwind and percussion instruments execute little figures that slow down, independently, to nothing.

So the music disintegrates. Far from the triumphant blast that ended the original version, this time the piece actually sounds as though it’s been abandoned. •