Studying the program guide for the must-see bands at a music festival is a bit like reading the form guide for the Melbourne Cup. You can spend hours analysing a seemingly endless array of ponderous testimonials only to emerge with an extremely well-compiled list of losers. While it’s true that the favourites sometimes get up, most of the time they don’t. The smokies – the come-from-the-clouds winners you’d never heard of – are the ones you remember. Prince of Penzance at around a hundred to one comes to mind.

Before the forty-first Port Fairy Folk Festival this year, I’d never heard of Mexrrissey; at least not until the evening of Day 2 when a strangely familiar tune that I couldn’t quite get a handle on wafted across to where I was stuck in a line for dumplings. I’d just come from seeing Les Poules à Colin, a band I’d taken on recommendation from a fellow festival-goer and one I might not have bothered with had I read the program guide. I’m not completely across “the alliance between Quebec trad and polyglot styles,” you see. Whatever they were doing up there, Les Poules à Colin did it well. We bought their CD after the gig, but not their t-shirt.

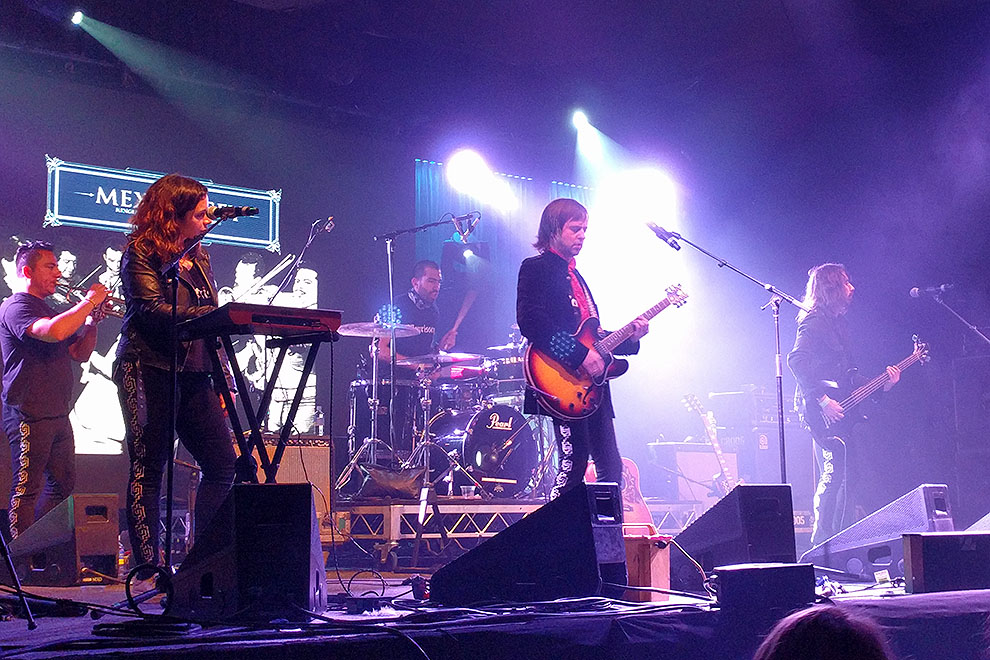

Mexrrissey – a seven-piece party band with some brass, a guitarist that looks like Frank Zappa, another like Noel Gallagher, a guy on keys with Jamiroquai’s hat and dance moves – were something else altogether. According to their website, they’re “a team of musical gunslingers from Mexico’s finest bands” brought together by their love of Morrissey, the kitchen-sink-realist frontman for eighties British phenomenon The Smiths. The members of Mexrrissey, so it goes, fell upon the idea that they could tour the world doing Morrissey tunes in Spanish. A Mexican band trawling Morrissey’s vast, misery-ridden catalogue in a language I don’t understand? What could possibly go wrong?

On paper, converting Morrissey tunes into Spanish is a bad idea. An appreciation for the sardonically brilliant Morrissey requires, if nothing else, an appreciation for nuance in the lyrics and how they’re delivered. Such wit, wisdom, irony and anger are easy enough to misconstrue in one’s own language, let alone in another. Regardless of which language, though, it’s a good thing that someone is doing The Smiths’ tunes; there’s no chance of the band ever doing them again, that much is known. On the likelihood of reforming, Morrissey once said that he’d rather eat his own testicles. He then underlined the sentiment by noting that he was vegetarian. That statement alone is grand testament to the difficulties of nailing down his oeuvre in Spanish.

In the end, the language didn’t matter. The tunes were familiar enough and Mexrrissey smashed it – that’s an industry term the kids are using these days; sometimes they extend it to food. I, along with a couple of hundred of my new best friends, was up on my feet shouting “Una Mas!” when the MC came out to announce the end of the show.

That Mexrrissey had anybody at all up on their feet at Port Fairy is an achievement worth celebrating in itself. As a first-timer to the festival, I was unaware of what everybody else seemed to know and brush off with a shrug of the shoulders. The Port Fairy festival patrons, you see, don’t like to move when they groove. After all, it’s notoriously difficult to pull off an Irish jig convincingly when you and those around you are, to paraphrase Paul Keating, Araldited to a camping chair.

They appreciate the music and the talent – that’s obvious – but they do so in very tidy rows, sometimes while knitting, reading the paper, tapping on their phones, knocking off a sudoku or two or sleeping, and often while commanding the best seats in the house for an entire day. “Dance friendly areas,” which are often nowhere near the stage, are signed and posted. They put their camping chairs there too. Sitting ovations are the preferred form of appreciation, and those who don’t know the rules, of which there appear to be many, are swiftly brought to heel. I, and many like me, were barked at, harrumphed, eye-rolled and waved off more than a few times, all for the crime of movement. By Day 3, they had me toeing the line.

Since returning from the festival I’ve had to answer the obvious question numerous times: how was it? I generally start from the same place – that I’ve been to my fair share of music festivals but that I was a little taken aback by the rules at Port Fairy. One review I’ve read since called it the “famously sedentary festival.”

After jumping on the festival website and having a dig around, I think I get it. There I found a photograph from the late seventies, when it all started, and it all happened, on the back of a flat-bed truck. It’s a bright, clear day, and while the detail is a little difficult to make out, a five-piece band up on the truck are brandishing some of the standard tools of the folkie trade: a fiddle, an accordion, a banjo and a couple of acoustic guitars. Out on the lawn before them, a few committed types are up on their feet dancing while the majority are sprawled out in the sunshine taking a more languid, and now familiar, approach to the on-stage proceedings.

Four decades on, the photo remains instructive. The DNA lives on. All of those instruments featured in the forty-first version of the festival, though a little more amped up and in a vastly broader array of genres. There is a fair chance that some of the people in that photo are still coming to the festival forty years on, and still in the same pose. But it’s important to remember that it is they who have supported it throughout its long history, and without them it’s unlikely there would be a festival at all. It’s easier, I’m sure, to book world-class talent when you know you’ve got a core group ponying up the cash every year for tickets and/or volunteering on a vast scale to keep it running.

And it’s not all sedentary. While the pockets of resistance that flare up in the main arenas from time to time are often quickly quelled, it’s easier to blow off steam at the off-broadway venues, both inside the main festival area and in the town itself. I finished that day, and the festival, in the Shebeen tent where the Guinness was flowing freely and a sweaty crowd was jumping up and down while a shouty, dreadlocked Dutchman led his band through a rollicking set of Dutch ska tunes. The well-oiled mob loved it, and there wasn’t a camping chair anywhere. •