Just six weeks into 2018 and it is already obvious that Donald Trump’s new year resolutions didn’t include making any positive changes in his behaviour and approach to government. He continues to tweet policy pronouncements and commentaries based on information gleaned from his favourite media outlets rather than official briefings and memoranda. The organisational chaos in the White House grows, as do the continuing efforts to undermine the Mueller investigation into collusion by the Trump campaign with Russia, all highlighted by leaks and exposés. Senior administration officials and Trump’s family continue to flout ethical guidelines and treat their positions as financial sinecures, and Trump’s policies — from taxes to healthcare to immigration to the environment — are rejected by large majorities of Americans. He gets some credit for the economy, but only one in five Americans believe his government has directly helped them.

Under such circumstances it might be expected that Trump’s approval ratings would continue to tumble. But they are slowly ticking up, with a poll average now putting him at 41 per cent, up from a low-water mark of 37 per cent in mid December (though this is still the lowest for any elected president at the one-year mark since modern public opinion polling began).

It seems that for roughly four in ten Americans, nothing Trump has said, done or failed to do has mattered in the least. Republicans have increasingly bound themselves to Trump, allowing him to redefine the party in his image. The Republican-led Congress has become an adjunct of the White House; even those such as Senators McCain, Corker and Flake who are willing to voice their opinions are unwilling to vote against Trump’s initiatives. The president has tremendous power to sway public opinion, especially his base, and control media attention, even as his own opinions so often reflect those of the last person he talks to. Not surprisingly, it has been argued that he has made opinion polls meaningless.

The focus on the polls and their meaning is in large part driven by the November midterm elections and their consequences. There are two common assertions about how these elections will affect Congress: that the president’s party almost always loses seats, and that the fate of the president’s party is directly tied to his approval ratings. A Democratic wave in the midterms would prove that the laws of political gravity do still apply and would bring with it the chance to change congressional politics, to push back on Trump’s agenda, and even to threaten his impeachment.

Pollsters are already doing their analyses. Chris Cillizza, Charlie Cook, Bloomberg and others are all previewing wins for the Democrats in November. By contrast, Larry Sabato lays out scenarios where 2018 could be a disaster for Democrats and Nate Silver at FiveThirtyEight cautions that the Democrats’ Senate chances might be overrated. The reality is that elections are some way off and it’s not possible to predict the issues — local, national and international — on which they will be fought.

One factor that might significantly affect votes in November, especially those of uncommitted voters, are signs of an emerging bipartisanship on some issues, something not seen in Washington for a long time. Trump himself has called for bipartisanship on immigration and infrastructure, knowing that he will need Democratic votes to pass legislation that is deemed too “soft” by conservatives such as the House Freedom Caucus. But he has quickly undermined this appeal with insults and attacks.

Immigration is a case in point. It has been a toxic issue in US politics, not helped by Trump’s nativism and xenophobia: during his campaign he likened immigrants to a deadly snake that bites the person who shows it kindness. For a country that depends on immigration for both skilled and unskilled labour, Trump’s approach is economic poison that will cost taxpayers billions.

The current immigration issue and the urgency of its resolution exist because Trump, acting in accordance with his campaign promises, declined to renew President Obama’s orders on the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program, which now expires in early March. Without action, some one million young people who call America home (the so-called Dreamers) could be deported — although this deadline has recently been extended by two federal court decisions requiring continuation of the DACA protections. It is within Trump’s purview to give the Dreamers legal status and a pathway to citizenship, but — true to form — he wants something he can call a political victory for his supporters. What that might be has changed multiple times, but it involves sharp cuts to legal immigration programs and funding for increased border security, and expanding the wall on the Mexican border.

Appraisals of the costs and contributions of immigrants sharply divide the political parties and particularly the Republican Party. Legislation allowing DACA recipients to become American citizens will split the GOP wide open — there is no way the most conservative tranche of the party, the forty or so members of the House Freedom Caucus, will support it. The only way forward is for the Republican leadership to work with the Democrats on a compromise. Last month, Trump told law-makers from both parties to craft a “bill of love” and said he would sign it. Then, just a few days later, using vulgar terms, he rejected a bipartisan compromise from Senators Durbin and Graham.

Democrats might have lost the battle to link DACA legislation with the legislation to keep the government functioning, but they did manage to extract some commitments about how to move forward from Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell. The Senate is currently engaged in efforts to deal with DACA in the way the Senate is supposed to function — with open debate and amendments. But it’s impossible to know how these efforts will turn out — or, indeed, if they will deliver a resolution of the issue. There doesn’t appear to be any compromise that can get the needed sixty votes.

Trump’s role is an added complication. His inconsistent behaviour makes it difficult for both Democrats and Republicans to negotiate with him. In one sense, it is easier if his role is minimised; on the other hand, his support will be necessary to drive the passage of legislation acceptable to the Senate through the House, where the right will baulk at any idea of compromise with the Democrats. It’s possible that Trump will sign whatever is sent to him and claim victory. But it’s equally possible, especially now the courts have removed the DACA deadline, that Trump and the Republicans will see congressional action as less urgent and will continue to use immigration and border security as campaign issues.

This would continue the partisan divide over immigration. Trump would appeal to his rusted-on supporters and the Democrats would capitalise on the substantial support from Americans of all political persuasions for granting Dreamers legal status, as well as the fact that a majority are opposed to building the wall along the border with Mexico. It is likely that Latino Americans (who are most affected by DACA) will be energised to go to the polls, posing a danger for Republicans in states like Nevada with significant and growing Latino populations.

And it is not just Latinos who are being galvanised into action. Democrats are increasingly optimistic they can mine Trump’s divisiveness and the White House turmoil to pick up the twenty-five seats they need to win back control of the House of Representatives. Their plan is to target 101 congressional House seats currently held by Republicans — the largest such effort in a decade —with expansion into solid Republican territory in states like Alabama, South Carolina and Texas.

The path to a majority in the Senate is harder, with the odds clearly in the Republicans’ favour. The Democrats must win all of the twenty-six seats they are defending and two of the eight Republican seats that are in play. In addition, recent polls have shown that the Democrats’ lead in the generic ballot test, a key measure for congressional races, has dropped from thirteen points in December to around seven points.

The Democrats claim their own polling of key districts has been more promising than national trends, and this is boosted by recent election results. Democrats took back the governorships of New Jersey and Virginia, won the Alabama Senate race, and won a significant number of state legislature seats in districts previously carried handsomely by Trump.

This will not be an easy task, and to win Democrats must counter infringements on minority voter rights, gerrymandering, predicted Russian interference and the huge amounts of money that will be poured into campaigns by Republican donors like the Koch brothers, who plan to spend a record US$400 million to “change the trajectory of [the] country.” One of the lessons of the Alabama Senate race was that getting out every vote, especially the minority vote, will be crucial. This means offering more than Trump-bashing, with policies to address voter concerns about healthcare, urban and rural poverty, the environment and climate change.

Perhaps the Democrats’ biggest advantage will be the huge number of candidates wanting to run, with many of these Democrat challengers outperforming the Republican incumbents in early fundraising. Thanks in part to Trump’s misogyny and the power of the #MeToo movement, it is predicted that this could be the Year of the Woman. There are currently 325 non-incumbent candidates for the House of Representatives, with seventy-two female members seeking re-election. In the Senate, thirty-eight women are challenging and twelve incumbents are running again. The majority of these women are Democrats. Trump’s approval rating among women has fallen to 29 per cent, with his ratings falling even among white women in the rustbelt, who voted for him in droves.

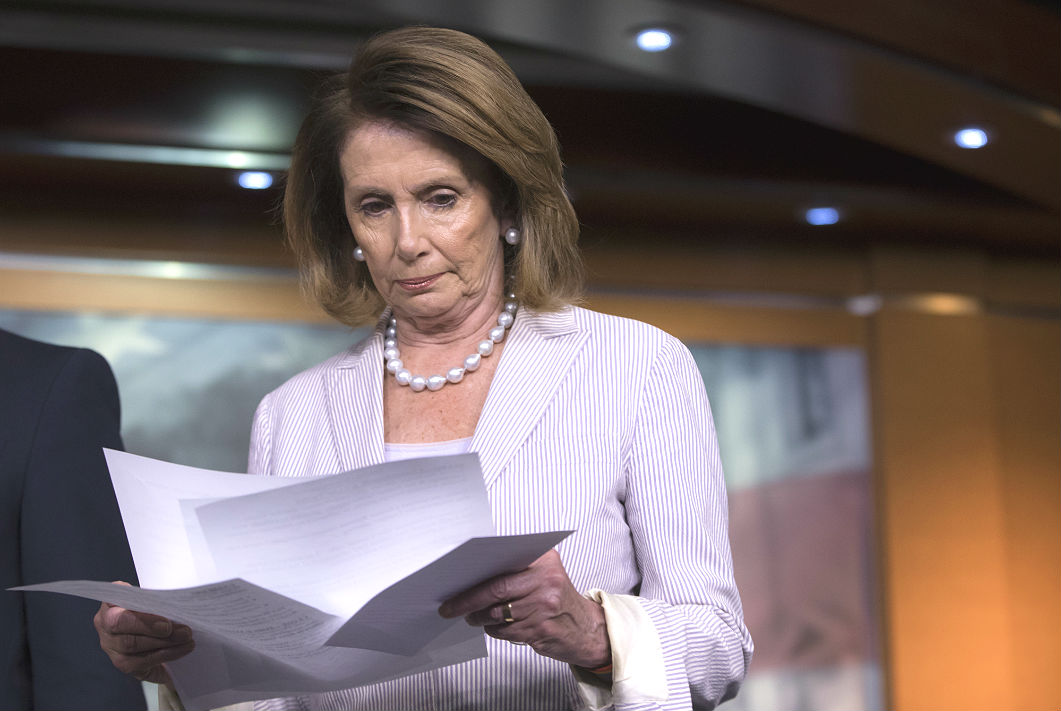

Yet one of the biggest problems for Democrats is seen as House minority leader Nancy Pelosi. Despite her political smarts and her fundraising abilities, many see her as a liability for her party. Republicans think she is politically more toxic than Trump, and they plan once again, as they have done since 2010, to build their midterms playbook around her as a symbol of the Washington insider and of liberalism run amok, and portray her leadership as the dire consequence of a vote for the Democrats. It could look like Clinton vs Trump all over again. ●