The Association of Southeast Asian Nations summit in Sydney was the first on Australian soil. Yet it was a meeting based on a lot of shared history over ASEAN’s fifty years.

Australia has always thought ASEAN a good thing. The hard question, always, is what good Australia can do with ASEAN. The answers offered by prime minister Malcolm Turnbull played back to ASEAN its own rhetoric by embracing the grouping as the region’s strategic convenor:

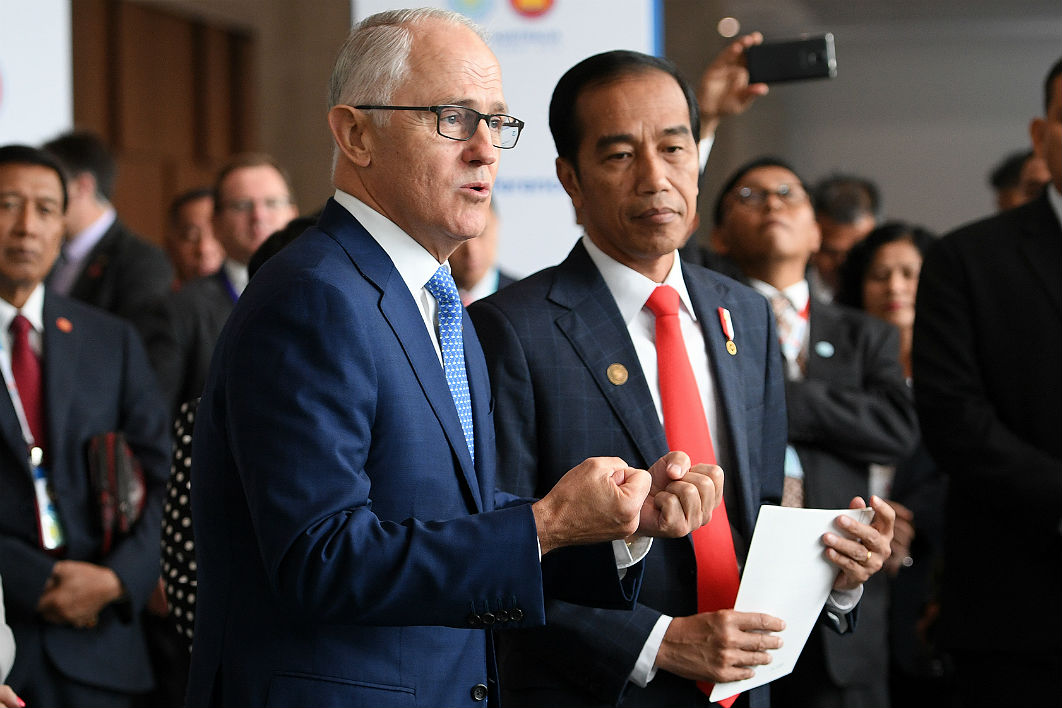

Today is a historic day, as the leaders of ASEAN and Australia come together for the first time in Australia, working together here determining our commitment to the centrality of ASEAN and our commitment — commitment of Australia to ASEAN at the very heart of the stability, prosperity, security of our region. The meeting comes at a critical time for the region. The pace and scale of change is without any precedent in human history. Our vision is optimistic and born of ambition — it’s for a neighbourhood that is defined by open markets and the free flow of goods, services, capital and ideas. Over the past fifty years, ASEAN has used its influence to defuse tension, build peace, encourage economic cooperation and support to maintain the rule of law. And we are fully committed to backing ASEAN as the strategic convenor of our region.

As with any summit communiqué, the Sydney declaration serves as both a paper vision and a wallpaper covering, showing what can be agreed and gliding over the differences. The declaration of “a new era in the increasingly close ASEAN–Australia relationship” is summit-speak with a basis in fact.

That closeness — what I’d call a growing “big fact” of Oz diplomacy — is the ASEAN flavour of much of Oz foreign policy. As an example, our policy on Myanmar over recent decades has been the ASEAN recipe with added Oz rhetorical sauce. No surprise, then, that the strongest public statement in Sydney on the Rohingya crisis was from Malaysia.

The rhyming and chiming of ASEAN–Oz policy reflects the reality of the many headaches we share. The times are getting tougher and the region’s most important middle-power grouping has much to discuss with its fellow middle power, Australia. The areas of vigorous agreement range across terrorism, trade and the problems of the times.

The signing of a memorandum on combating terrorism and violent extremism was the showpiece headline. The leaders also expressed a strong shared commitment to free and open markets, underlining “the critical importance of the rules-based multilateral trading system.” In the time of Donald Trump, this is suddenly more than a motherhood statement. As Turnbull noted, there are “no protectionists around the ASEAN table.”

Australia and four of the ASEAN states this month signed the “minus version” of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP minus the United States). Now Australia, the ASEAN 10, plus China, India, Japan, South Korea and New Zealand want to complete another deal this year: the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

About the South China Sea, Australia happily embraces and talks up ASEAN’s effort to get a code of conduct with China (oh, that we all live long enough to see it). Australia can also do sharper talk on the South China Sea, as it does in the trilateral strategic dialogue with Japan and the United States.

When it comes to walking the walk, though, Australia tends to do the ASEAN shuffle. In the words of foreign minister Julie Bishop, Australia rejects “any unilateral action that would create tensions and we want to ensure that freedom of over-flight and freedom of navigation in accordance with international law is maintained and the ASEANs all back that same position.”

In the way the runes are read in Canberra, the foreign minister’s abhorrence of any unilateral-tension-creating action extends to any suggestion that the Australian navy should sail closer than twelves miles to China’s terra-formed sandcastles in the South China Sea.

An ironic area of agreement is that the times ain’t right for Australia to join ASEAN — yet. The discussion, however, has begun. A summit surprise was Indonesian president Joko Widodo, in a Fairfax interview, endorsing the idea of Australian membership of ASEAN “because our region will be better, [for] stability, economic stability and also political stability. Sure, it will be better.” An ASEAN-flavoured Oz foreign policy makes this idea thinkable and doable.

The big beasts of Asia, the United States and China, were naturally absent from the Sydney declaration. But their breath, as well as their tracks and their appetites, were a constant presence.

An ASEAN obsession now embraced by Oz foreign policy is the quest never to have to choose between the two beasts. Not so long ago, there was a significant chasm between ASEAN neutrality and Australia’s alliance addiction: we’re the nation proud to stand with our great and powerful friends. Today, as the chasm shrinks or is defined away entirely, Australia, like ASEAN, doesn’t want to have to choose. We share much — including what we dread. •