For one who spent so much time surrounded by sharp-eyed artists and writers, Mollie Dean would prove a challenge to describe. She was “very, very attractive, very beautiful,” thought the painter Colin Colahan, and “knew her power with men.” She was “not really beautiful but had a certain sultry charm,” countered the playwright Betty Roland, being “somewhat sullen-looking with a well-cut sensuous mouth.” Passing moods lit her face from within: one writer thought her “plain in repose”; another evoked her “dusky glow.” A solitary photograph, widely published, is grainy and flat, lent character only by the eyes’ steady gaze and the jaw’s slight clench. Newspapers made up for its deficiencies with expressive prose: “Five feet, six inches [168 centimetres] in height, dark bobbed hair, dark complexion, well-set determined-looking features, little or no powder on face, slim to medium build”; “A good conversationalist, she had a low speaking voice, an excellent thing in a woman. Her avowed preference was for the society of men older than herself — a feeling that inevitably outgrows itself in time.”

The range of opinion reflected deeper ambivalence about Mollie Dean — a young woman resolved to get places, a young woman who when she got those places was not always welcome. Who was she? What was she? “She was an exceptional girl,” the cartoonist Percy Leason told reporters. “She had great vitality and charm and was particularly interesting. She was deeply immersed in literary questions and was writing a novel. I do not know what the novel was about. She was the sort of girl who would make light of such a work and not talk too much about it.” Leason’s confrère on the Bulletin, Mervyn Skipper, thought Mollie “the first liberated woman” he had ever met; Mervyn’s diarist wife, Lena, deemed Mollie a “sex aggravator,” “a rum girl with plenty of that schoolgirl way about her” hiding “in all her actions some monstrously selfish aim.” Roland complained that she had left “a path of havoc in her wake.”

All that most came to know of her directly was how that wake trailed away. For in November 1930, a month after her twenty-fifth birthday, Mollie Dean was slain in a laneway two minutes’ walk from her home — slain so sadistically that the press refrained from comprehensively listing her injuries. Intensified grief, idealised potential — these are the usual accompaniments of a tragically premature end. Not for Mollie. An investigation petered out that no one, least of all the family from whom she was estranged, wished to revive; an inquest ensued, with an undertone of scandal it was in none of her friends’ interests to prolong.

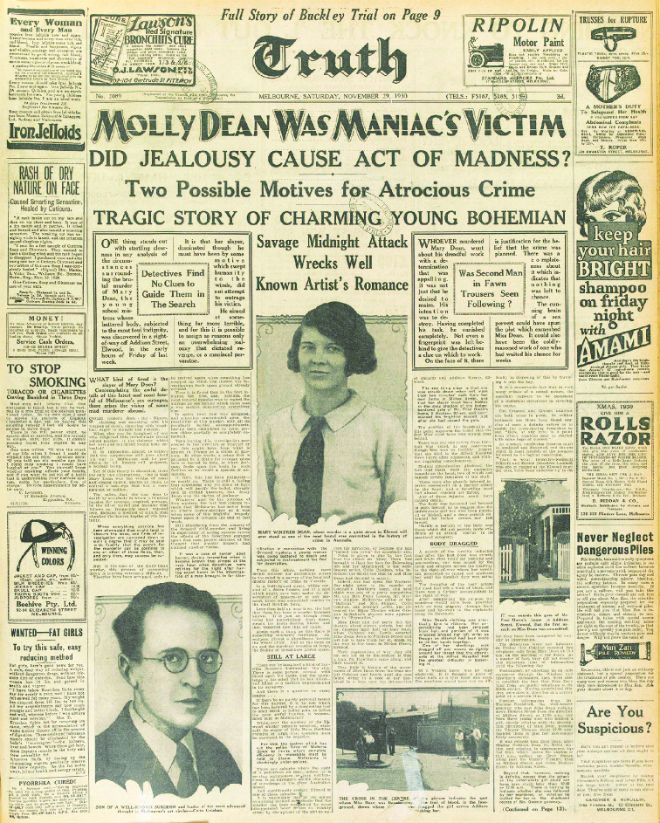

Act of madness? Truth’s report on the murder.

As for her life, a good deal of Mollie’s adulthood had been spent in the fugitive role of the “other woman,” whose tracks are ideally self-obscuring. Her correspondence, purportedly racy, conveniently disappeared; likewise the manuscript of her novel, never finished. At Montsalvat, the Eltham art colony where many of her former circle settled, her name would be uttered only in muted tones. In art history, she has condensed to a curio. Misty Moderns, an extensive 2008 touring exhibition by the National Gallery of Australia, touched off a reappraisal of the artists with whom Mollie circulated — the quasi-scientific, objectively minded disciples of “tonalism” such as Colahan, Leason, Justus Jorgensen, Clarice Beckett, Archie Colquhoun and, above all, their inspiration, the peppery controversialist Max Meldrum. Mollie was a line in the exhibition’s genre chronology: “November 1930: Murder of Colin Colahan’s girlfriend, Mollie Dean. Impact temporarily disrupts Colahan’s artistic trajectory.” No reflection was invited on the permanent disruption of Mollie’s “artistic trajectory.”

Mollie Dean’s shadow lengthened by other means. She who had aspired to fiction inspired it instead — affirming Edgar Allan Poe’s aperçu that “the death… of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.” Generations of Australians have been unknowingly familiarised with her story through the pages of George Johnston’s My Brother Jack.

Johnston never knew Mollie Dean; rather, more than twenty years after events, did he fall in with the gregarious Colahan, who became a friend and familiar in addition to painting Johnston’s wife, Charmian Clift. The murder had by now become part of Colahan’s extraordinary repertoire of stories; Johnston was transfixed. As his great novel took shape years later, he repurposed the relationship between artist Colahan and muse Mollie as the tale of star-crossed student painters Sam Burlington and Jessica Wray, who introduce Johnston’s callow alter ego, David Meredith, to Melbourne’s la vie de bohème.

It is an atmospheric telling. Jessica is first glimpsed hastily “fastening the buttons of her blouse,” fair hair suggestively loose. She reacts to Meredith’s unexpected arrival at Burlington’s bachelor pad by saucily withdrawing: “The blonde girl went away soon after I arrived. She and Sam talked together for a while in the passageway in low voices, with a lot of smothered giggling on her part, and I heard her say, ‘But it’s high time I went home anyway, after the way you’ve been carrying on, you devil.’” Who is leading whom is rendered more ambiguous by Jessica’s cavortings with other girls at an apartment party that further discomfits prim Meredith:

I remembered my alarmed revulsion at the shameless exposed way the girls sat on cushions on the floor, with their knees carelessly apart in their short skirts and the shadowy disturbing gleam of naked thighs above their rolled stockings. I was shocked by their casual acceptance of drinks and cigarettes, by the candour of their conversation, by their abandoned submission to kissing and petting.

The apartment is dominated by Sam’s “not quite finished but extremely frank” nude canvas of Jessica. Brother Jack, archetype of vernacular common sense, glowers at the painting disapprovingly when he arrives amid the bacchanal:

“Who did this thing?” he wanted to know.

“Sam,” I said.

“Cripes! It don’t leave much to the imagination, does it?”

“Oh, stop this stupid business Jack,” I said.

Though Jack warily embraces the festivities, his curiosity has been pricked. “You mean t’tell me,” he asks Sam, “she strips off an’ sits around starko and lets you paint her like that, without a stitch?” Sam’s slurred reply betrays a deeper unease with female sexuality: “Yesh, sir, thash my baby. Jesh. Look at her over there, eh. Jush look at her! Beau’ful girl. Talent too. No morals. Wassit matter? She’d sleep with you. Me. Anybody.”

When Meredith encounters Jessica and Sam next, their images are staring from the grey columns of the Morning Post, where tyro journalist Meredith is working. Jessica has been murdered in a park, and suspicion has fallen on Sam. The prurient turn of his hitherto “conservative, old-fashioned” employer tips Meredith into crisis. He must bear witness to his trade’s pandering to gossipmongers and breakfast-table moralists — including his own censorious father. He must reconcile Sam’s travails with his own self-preserving instincts — a challenge he squibs in Petrine fashion, thrice denying his friend. He must even answer for his own titillation, with which a detective cannily confronts him: “She was a very pretty girl, wasn’t she? Did you find yourself attracted to her?… Didn’t you ever wish it was you doing the canoodling and not Burlington?”

Ere long new evidence dispels the tension, and around the murder itself My Brother Jack ends up rather skirting, exploring it only in terms of the consequences for others. Like Colahan, Sam departs Australia; unlike Colahan, he abandons art; the experience turns Meredith into, by his own admission, “a master of dissimulation,” in ways that ramify through the whole trilogy. Yet, rereading the novel after many years, my own curiosity, like Jack’s, was engaged. Didn’t this book draw on Johnston’s experiences? If so, to whom did he owe Jess and Sam?

Nor was George Johnston alone in being beguiled by the life and death of Mollie Dean. In adapting My Brother Jack to the screen in the mid 1960s, Charmian Clift viewed her from a slightly different slant, struggling to reconcile life and art — in much the same way as Clift.

At least three writers who knew Mollie, I was to learn, drew on her in fictional works of differing descriptions. And she has undergone in the twenty-first century an improbable renaissance: becoming the subject of a play (Melita Rowston’s Solitude in Blue) and a song (The Dusty Millers’ “Molly Dean”), swelling the progress of an acclaimed literary novel (Kristel Thornell’s Night Street) and starring in her own whodunit (Katherine Kovacic’s The Portrait of Molly Dean).

Who was she? Perhaps whomever we wished her to be. But behind the myth lay a human soul needing to tell her own story, and helping in that task seemed worthwhile. ●

This is an edited extract from Gideon Haigh’s A Scandal in Bohemia, published this month by Hamish Hamilton.