Life can be exhilarating. And sometimes it can be disappointing. Sometimes it can be both at once. Melbourne is a prime example.

In just a decade, Melbourne has added more than a million people. It began this century with 3.4 million people. By September, on current estimates, it will have five million. In less than twenty years, its population has grown by roughly half.

That’s exhilarating. The city today has a buzz that it lacked twenty years ago. In the year to last June, an extra 125,000 people packed into Australia’s fastest-growing city. They included a net 80,000 overseas migrants, students and workers, as well as a net 9166 people, overwhelmingly young, from the rest of Australia. It gained a net 14,400 migrants from Sydney (but lost some to regional Victoria and Queensland). And there were a record number of births, because the city is now full of people in their twenties and thirties, and so babies keep popping out.

In that one year, Melbourne’s population grew by 2.65 per cent, the rest of Australia by 1.35 per cent. If this pace keeps up — and it has, more or less, for far longer than any of us expected — it will overtake Sydney within a decade to reclaim the title of Australia’s biggest city, a title it lost in 1902.

If growth is what you want, Melbourne’s got it. More to the point, it’s got it whether you want it or not.

But for many, the population growth transforming the city is more disappointment than exhilaration. In theory, governments can manage any level of population growth as long as they match it by investing heavily in infrastructure and providing expanded services. That was the key issue behind yesterday’s Victorian budget, in which treasurer Tim Pallas set out to do just that — at least for the coming year, when the government is facing an election.

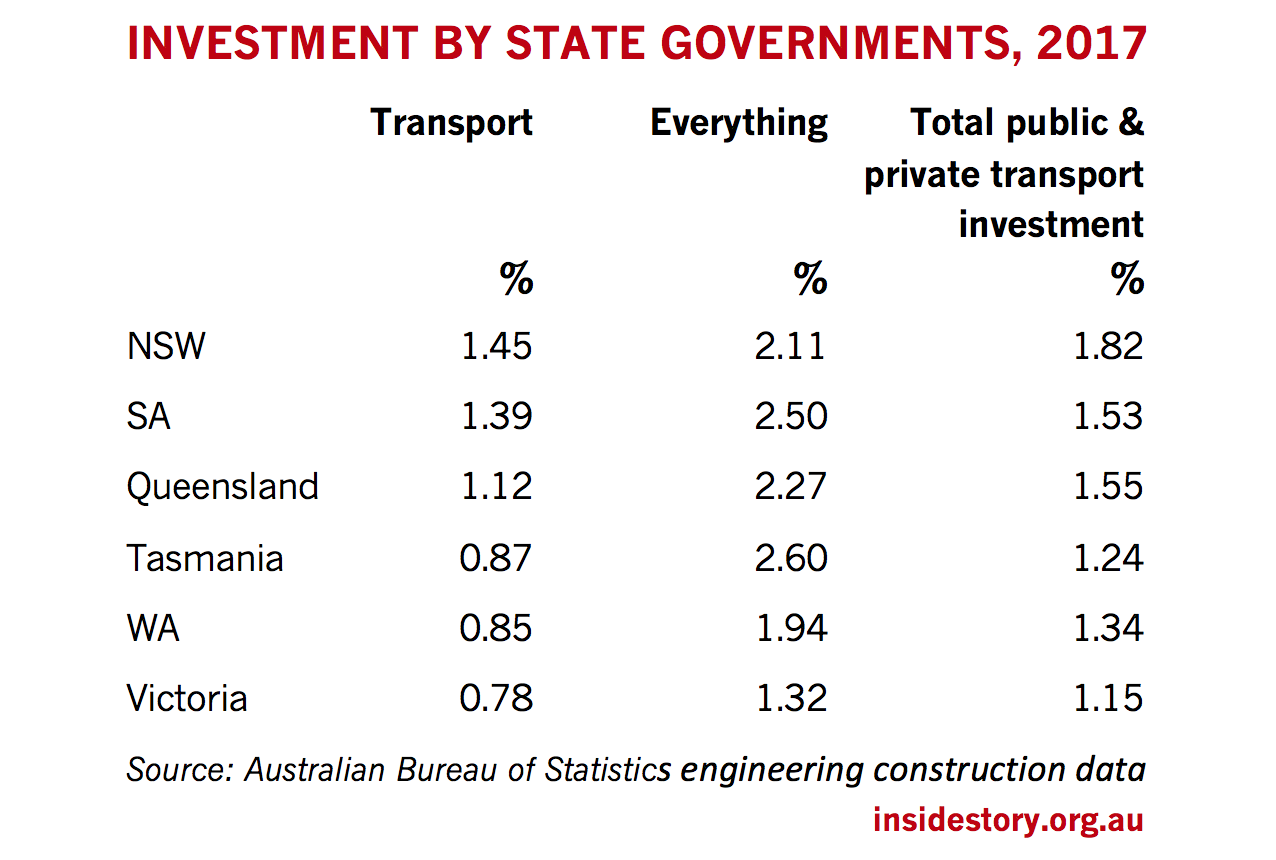

But until now, that is not how the Victorian government has been run. As the table shows, it has been a chronic under-investor. Even in 2017, its investment in transport infrastructure generally, as a share of economic activity, was the lowest of any state, whereas its population growth has been the highest. Victoria has lived off the capital built by past governments.

Tuesday’s budget papers confirm that the roads have become far more congested; the past five years have brought 14 per cent more people, but only 1 per cent more road space. The growth in public transport passengers has flattened off, perhaps because people now look back nostalgically to the days when you could board a train or tram and get a seat. And while there are several reasons why ordinary young couples can no longer afford to buy a house, population growth is certainly one of them.

If the city keeps growing at this pace, the five million Melburnians of 2018 will become ten million by 2045. Melbourne has prided itself on being, as one survey keeps reporting, “the world’s most liveable city.” It was less congested than Sydney, its houses were cheaper, its train and tram networks were something to be proud of. All that is now disappearing before people’s eyes.

While those issues underlay yesterday’s Victorian budget, the politics was front and centre. There’s a state election on 24 November, and the Labor government of premier Daniel Andrews wants to be sure it gets back. Policy debates are all very good, but the policy of this government is to stay in power. Yesterday it left nothing to chance, showering money for works on schools and roads, hospitals and sports grounds, mental health programs, regional Victoria, and trams, trains and TAFEs.

Treasurer Tim Pallas put out a positive spin, reeling off his own exhilarating numbers on the growth of the state’s economy, and on its budget spending. Since Labor won power three and a half years ago, he said, Victoria has become the fastest-growing state. The output of its economy has grown by almost one-seventh in that time. It has added 334,000 jobs, more than 200,000 of them full-time. Housing and investment are booming.

And so the budget is awash with money. In some ways, the key figures of this budget are its dramatic revisions to estimated revenue and spending in the election year, 2018–19. The state now expects to rake in $7 billion (11.5 per cent) more revenue than it had forecast just two years ago — and to spend an extra $7.6 billion (12.5 per cent) on expanding the services it offers Victorians, almost across the board.

Why is revenue so much higher than Victoria’s Treasury had anticipated? Partly because soaring house prices have pushed up land transfer duties and land tax revenues. Partly because the Turnbull government keeps wanting to spend more in areas the states run — even if it discriminates against Victoria on transport investment — and partly because even GST collections are booming, and Victoria’s share is being pushed up because its share of the population is soaring.

Because this is an election budget, there are no tax increases and no spending cuts — at least, none the government owns up to. But a table in one budget paper shows that almost $2 billion of unspecified cuts will be made over the next four years to “reprioritise” spending, so that existing programs will be dumped or trimmed to pay for new ones. And we’ll never know what will be cut.

The new spending initiatives go almost everywhere — social housing was almost the only area to miss out, despite the crisis facing low-income renters in Melbourne. The new mental health spending is significant, the list of schools receiving upgrades runs for twenty-six pages, and a catchy policy offers a $50 payment to any households that sign into the state’s Energy Compare website to investigate how they can reduce their power bills. (The budget numbers imply that they expect almost a million households to do exactly that.)

A lot of care has been taken to ensure that regional Victoria gets its share of projects in almost every area — highlighted by a decision to reduce payroll tax there to only half the rate paid in the city. Melbourne is growing twice as fast as the rest of the state, and the government wants to move more of the action to the bush. A recent audit report found that in the decade to 2016, economic output actually shrank in half the municipalities of regional Victoria, including Mildura, Wangaratta, the Latrobe valley, a vast swathe of western Victoria, and even East Gippsland, where the retiree population is booming but jobs are not.

But Andrews and Pallas highlighted two areas in particular: skills and infrastructure.

A package of reforms to the neglected TAFE system is headlined by a surprising initiative to make thirty courses free of charge throughout the state. At the highest (diploma or certificate IV) levels, they include accounting, ageing support, agriculture, building and construction, engineering, plumbing, nursing, mental health, and other health and welfare roles.

The government will also fund 30,000 more training places, upgrade or add seventeen new campuses, largely in country towns, expand career guidance in schools, and begin a program to allow students to enter an apprenticeship while still at school.

The aim, Pallas said, was to challenge the assumption that kids have to go to university if they want to succeed in life — and help them become the skilled workers needed for the future Australian workforce. “Skills are the centrepiece of this budget,” he told me. “This is a Labor budget that will deliver new skills and good jobs.”

The other main theme of this budget is infrastructure. In this coming election year, the state plans to invest $13.7 billion on infrastructure, including investments by private companies such as Transurban on projects they operate for the government. In its first budget just three years ago, the Andrews government invested a puny $4.8 billion. At first sight, that is some policy shift — and a recognition that the combination of rapid population growth and inadequate investment is destroying Melbourne’s liveability.

(This figure is much higher than the one in the table above for several reasons. The earlier figure measures engineering construction, which covers most infrastructure investment, especially in transport. The government’s figures also include investment in buildings, machinery and equipment, investments by its private-sector partners — and, of course, a sizeable increase in spending between 2017 and 2018–19.)

But it’s only temporary. For the Andrews government remains bound by its commitment to keep net government debt to a minuscule 6 per cent of gross state product, the share it inherited from the Liberals. The protracted sale of the Port of Melbourne brought the debt down, and now, over the three years from 2017 to 2020, a big increase in infrastructure investment will push it back up to that low ceiling. One might note that the federal government’s net debt, by contrast, is roughly 20 per cent of GDP — and it still has a AAA credit rating.

The budget also warns us that this investment surge is a one-off. After the election, as it nears its self-imposed ceiling, the government would go back to being a chronic under-investor. Its investments and those of its private sector partners will hit 3 per cent of gross state product in 2018–19, only to then slide back to 1.5 per cent in 2021–22, and resume its usual ranking at the bottom of the table.

Unless you believe it will have fixed the infrastructure backlog by then, that is economically indefensible. Bond rates have edged up a little, but it is still very cheap for governments to borrow, and with the population on track to double within a generation, Melbourne’s needs remain immense. The government’s decision to impose such a low debt ceiling, and to maintain a AAA credit rating at all costs, are driven by politics, not economics. Queensland lost its AAA credit rating when premier Anna Bligh rightly gave priority to infrastructure investment — yet the rates it pays on its debt are only between 0.1 and 0.15 percentage points higher than New South Wales. It really makes very little difference in the markets.

In effect, Victorians are paying the cost for believing that Labor governments are fiscally more irresponsible than Liberal ones. But there are many ways to be irresponsible, and investing too little can be as irresponsible as spending too much.

For these three years, at least, Victoria will be investing across a wide canvas of transport projects. Its own investment in transport infrastructure has risen from $2.5 billion in 2015-16 to a planned $7 billion in 2018-19. That includes:

• $1.1 billion on its blitz to remove fifty level crossings from Melbourne roads. That is one of Labor’s flagship projects, funded by the state alone — although unfortunately, as the auditor-general has pointed out, they are not the fifty most dangerous or congested level crossings in Melbourne. Inconsequential level crossings in marginal seats on the Frankston line are being removed while the level crossing in Liberal-voting Surrey Hills, which VicRoads has ranked as one of the city’s worst on both counts, has been left to keep blocking busy Union Road.

• $319 million as the state’s share of works on the controversial West Gate Tunnel project, a Transurban plan adopted by the government despite the best efforts of the Liberals, Nationals and Greens to block it. The government has adopted a sneaky plan by which most of the bill will be footed initially by Transurban, but the bill will ultimately be paid by drivers on CityLink, the overpriced inner-suburban freeway, for which Transurban’s lucrative franchise has been extended for another decade.

• $571 million for another of Labor’s flagship projects, the $11 billion Melbourne metro tunnel, also entirely state-funded, which will take a decade to build. (Why can they do these things so much faster in Asian cities like Delhi and Singapore?)

• $453 million of essentially Commonwealth-funded works to upgrade the Ballarat and Gippsland rail lines. This was the legacy of former federal infrastructure minister Darren Chester, Gippsland’s MP, who used the deadlock between Malcolm Turnbull and Andrews over almost every project in Melbourne to focus the small amount of funding the federal government gives Victoria on rural roads and rail.)

• $375 million to transform the rail line from Cranbourne/Pakenham through the city to Sunbury, including a new signalling system, longer platforms and upgrading those essential, inconspicuous and often-overlooked things like power supply. Another $58 million will complete the controversial Skyrail project, to open later this year, which has elevated the rail line through some southeastern suburbs to scrap level crossings. The Murdoch press, which supports the Liberal government doing this in Sydney, has depicted it as an outrage against human rights under a Labor government in Melbourne.

• $123 million to plan the $16.5 billion North East Link from Greensborough to the Eastern Freeway — to include a significant widening of the freeway through the middle suburbs. But in a marked difference from the way the Liberals rushed through the controversial and economically unviable East West Link before the 2014 election, Andrews says no commitments will be made until after the election. Liberal leader Matthew Guy says that, if elected, his party will build the East West Link first.

And there’s much more. A lot of money will be spent all over the state to upgrade, widen, rebuild and repair Victoria’s rural and regional highways and arterial roads, and a lot more to tackle urban congestion. There will be new trains, trams and rail carriages. The government deserves a pat on the back for committing $200 million or so of its revenue windfall to lift spending on road maintenance, where the statistics suggest an alarming deterioration. It needs to do the same for bridges, after a recent report rated two-thirds of the state’s bridges as being in poor condition.

Where is the Commonwealth government in all this? On the fringes. Its own figures have consistently shown that Victoria is getting only 10 per cent of its infrastructure outlays, even though it has almost 40 per cent of Australia’s population growth. Both governments share the blame for the juvenile stand-off in which the Turnbull government refuses to support anything that the Andrews government supports, apart from widening the Western Ring Road and the Monash Freeway.

Turnbull’s latest stunt is to offer $5 billion to build a rail link to Tullamarine airport — provided that the route is changed to run through land the federal government is trying to sell, and the federal government takes 50 per cent ownership of the rail line. The offer was shared with the Murdoch press before it was shared with the Victorian government — which understandably has ignored it. When the federal government announced its support for a rail link to the Western Sydney airport, it was with no conditions, and at a joint press conference with the NSW premier. That’s how governments are meant to act.

Whatever route is chosen, the rail link can’t run through the city before the new metro line opens in 2026. Infrastructure Victoria rates the whole project as only a distant priority anyway, given that the Tullamarine Freeway widening is almost complete, which will see Skybus get to the airport as fast as a rail link could. And the polls suggest that in a year’s time, Turnbull will no longer be prime minister, and a federal Labor government would finally treat Victoria with the respect — and priority — it deserves.

After a rocky period last year when the Herald Sun commissioned opinion polls whenever things looked bad for Labor, the polls in recent months have suggested that Labor is likely to be re-elected. It’s still close — Labor polled 51–49 in the last Newspoll, 52–48 in the one before, and even better in the latest Essential poll — but what is striking is that Andrews’s personal ratings have rebounded to roughly where they were at the 2014 election. Among the mainland state premiers, the only other to achieve that feat in recent times was Annastacia Palaszczuk, who was also the only one to be re-elected. The Liberals, who seem obsessed with battles within the party, have simply not cut through.

This is a soft budget. With all that new revenue and infrastructure spending, the anticipated surplus in 2018–19 is a skinny $1.4 billion, down from about $3 billion when Labor took office. In state budgets, the surplus is essentially the contribution current taxpayers make to infrastructure spending. With Victoria’s economy where it is, the surplus should be at least $5 billion now, but Labor has used the good times to put off hard decisions, allow wasteful programs to continue — for example, paying people in uniforms to walk up and down every suburban train station at night, to make passengers feel safe — failing to tackle tax reforms, and allowing the state’s wage bill to blow out by an extraordinary 38 per cent in its four years in office — including an 11.2 per cent increase in 2018–19 alone.

If the economy keeps going well, it will get away with it. If the economy turns down, as well it could, this slack management will cause Labor serious problems ahead. Right now, the public is paying no attention.

This budget was labelled “Getting things done.” Last year it was “Getting on with the job.” Whatever Andrews’s faults and limitations, he is dogged, competent and, yes, can say that he is getting things done. People might not like him, but he has earned a grudging respect. And he, and Pallas, have been lucky to be in office at a time when the state economy is booming. Naturally, they claim the credit. ●