My partner nudged me as we walked towards the car after a recent theatre performance. Following her gaze, I saw one of the actors we had just applauded in the darkened theatre, dressed now in checked shirt and jeans, striding purposefully across the road. Ignoring the crowd of loitering theatregoers, he turned the corner and disappeared.

“I find that so strange,” she said. Then she added, “I don’t suppose you do.”

I spend more time in the audience these days than on the stage, but I understand that jolt when the willing suspension of disbelief you have engaged in for hours is broken as you return to the world outside the theatre, especially when someone from that enclosed world appears before you stripped of the trappings of his character.

The view from the stage, with all senses on alert for the response from the people in the auditorium, is a quite different experience. The pleasure is in knowing the audience is with you, laughing in the right places, pin-drop silent at moments of tension; the anxiety flows from actor to actor when laugh lines fall flat, when the audience is restive or, worse, when you can see or hear people walking out.

My most memorable stage–audience interaction occurred on 1 December 1972, election eve, when the electricity in the air was palpable and Chris Haywood even threw in a few ad-libbed quips in his role as the cheeky Cockney-accented removalist in David Williamson’s play. The buzz circulating through the now-defunct Playbox Theatre in Phillip Street, Sydney, had originated in the sighting of the unmistakeable figures of Gough and Margaret Whitlam in the second row. It is hard to imagine such a thing happening with our present crop of politicians, and even harder to imagine the excitement the “It’s Time” election had engendered.

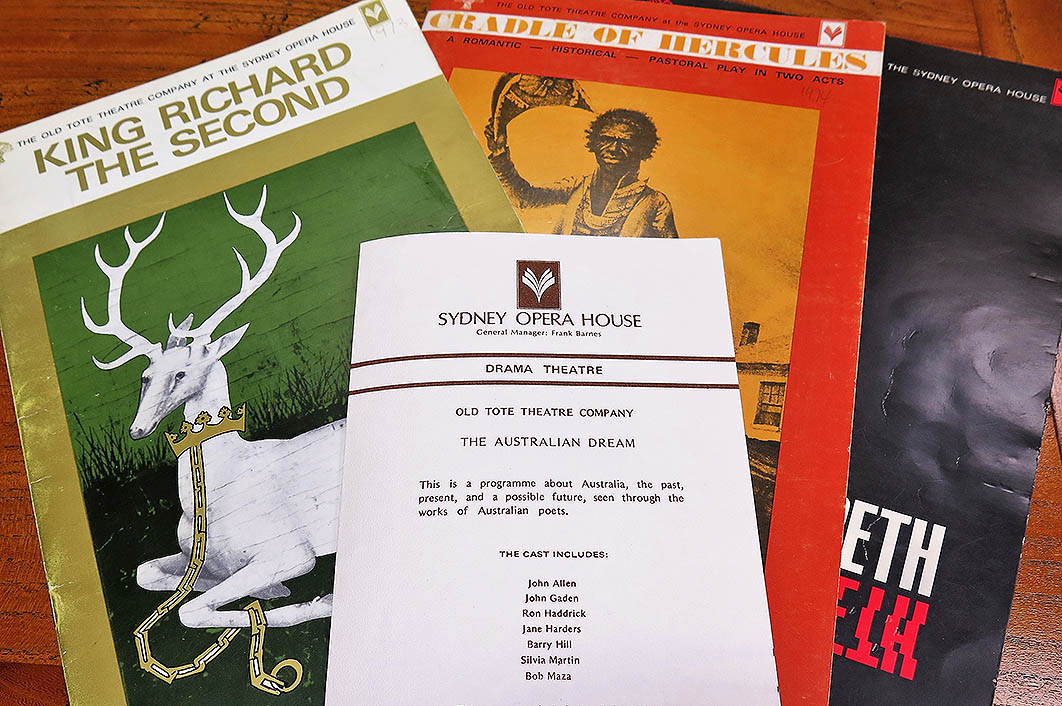

Complex choreography: programs from Old Tote Theatre productions at the Sydney Opera House.

I now write about characters rather than performing them, but my years as an actor in the 1970s and ’80s have been on my mind recently with the furore over the horse-racing projections on the Sydney Opera House sails in the lead up to the forty-fifth anniversary of the building’s opening by the Queen on 20 October 1973. Anniversary events have taken place and books are being promoted, Helen Pitt’s The House and Kristina Olsson’s novel Shell among them.

My memories of being a member of the Old Tote Theatre Company performing in the opening season at the Drama Theatre are part of the “inside story” of that time. I remember well the chaos when we moved into the theatre to rehearse. The Opera House was barely fit for occupation, air-conditioning was non-existent and we worked against a background of hammering and banging.

Most of the toilets weren’t yet connected, so we were obliged to scoot round to the administration wing. Even getting to the backstage area of the theatre was tricky. Negotiating the trek from the stage door through the cavernous belly of the building meant dodging trucks unloading stage machinery and workers transporting flats and shifting equipment on trolleys. I saw the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s instruments being crated in for the musicians to take up residence; they moved out again the same day, refusing to work under the conditions. (The musicians’ union must have been stronger than ours.)

The various resident companies held special performances during September to iron out acoustic problems and other challenges. The orchestra had a concert on the fifth in the Concert Hall, and six other actors and I, including the late Bob Maza, read the works of Australian poets in a one-night performance at the Drama Theatre called The Australian Dream.

Shakespeare’s Richard II opened the Old Tote season on 1 October, with John Gaden in the title role. I can still hear his plangent tones as he lay in prison in Pomfret Castle:

I wasted time, and now doth time waste me;

For now hath time made me his numbering clock…

The new theatre had some impressive features, although there was controversy over the company’s decision not to use the John Coburn–designed Curtain of the Moon, created for the Drama Theatre to complement the Curtain of the Sun in the Opera Theatre. What was used, some might say over-used, was the huge central revolve. The actors, particularly those of us with trailing floor-length costumes, had to employ nifty footwork getting on and off the moving sections without tripping or running into each other. The narrow wing space of the stage also made for some complex choreography among the large cast.

Michael Boddy’s Cradle of Hercules had been commissioned by the Old Tote for the 1974 season at the Drama Theatre. Exploring the relationship of the first settlers in Australia with the Aboriginal people, Boddy found “some little-known delicacy and grace in the relationship between Governor Phillip and the Aboriginal man Bennelong.” I am not sure how well it would stand up today, but the play was one of the first to feature Aboriginal actors in leading roles.

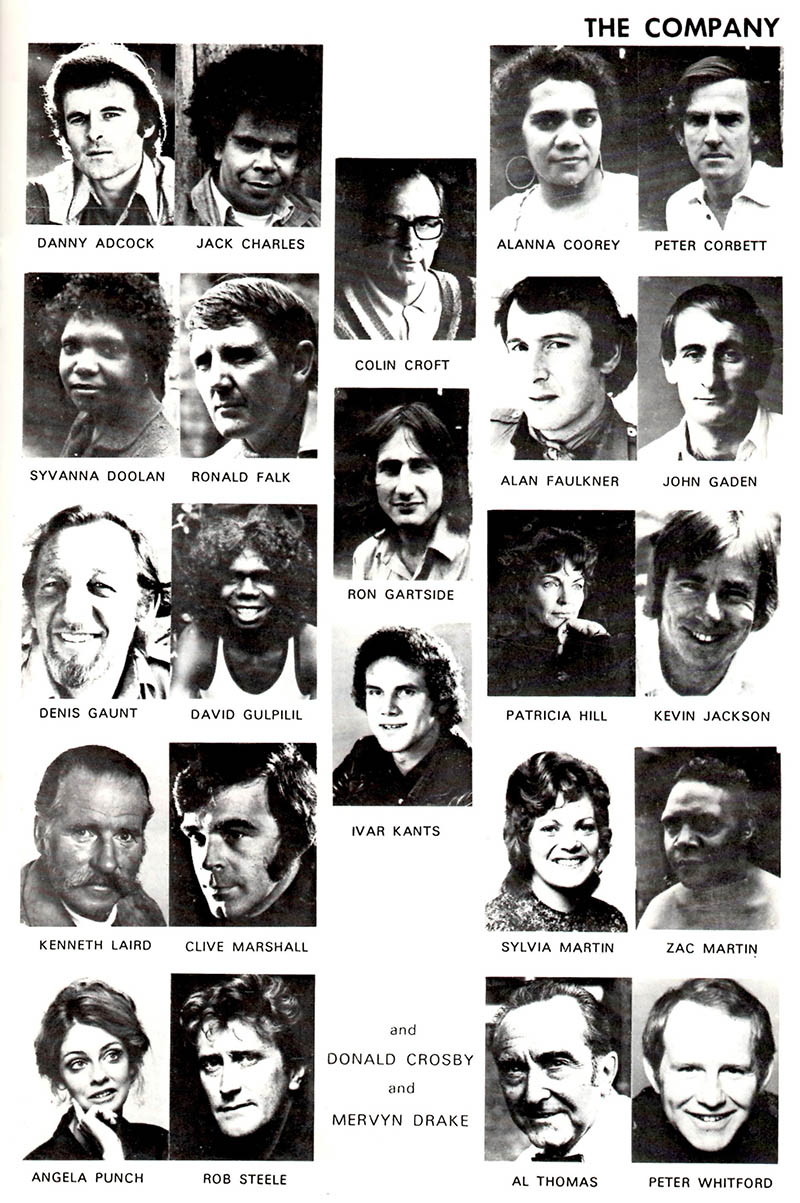

Pathbreaking: the cast of the Old Tote Theatre’s production of Cradle of Hercules.

One scene is ingrained in my memory. As Elizabeth Macarthur, I was in the unusual position of being part of an onstage audience when a select group of white settlers was treated to an outdoor dance performance by an Aboriginal man, played by an unknown young actor from Arnhem Land named David Gulpilil. His performance was different each night, as were the designs he painted on his body. Sometimes he would wander into the dressing room I shared with Angela Punch while we sat, laced into tight corsets under our voluminous dresses, waiting to go onstage. He would lean in the doorway or drape his long body over the back of a chair and explain the meanings of the earthy ochres of his body paint. One night he was a heron; I wish I could remember the others.

Perhaps because I was only on stage in a few scenes, my clearest memories are of the backstage world of the production. With a cast of more than twenty actors — listed under the headings of “Blacks, Naval, Military, Civilians and Convicts” in the program — there was always plenty of action in the brightly lit corridor outside the dressing rooms.

How to fill in time offstage is a perpetual problem for actors. Maybe they gaze at their phones now, but in the 1970s that was not an option. Getting lost in a book was out of the question. I have seen actors making tapestries and sketching, and several of the Hercules cast found productive pastimes: Mervyn Drake set up a table in the corridor and completed a large latch-hooked rug over the course of the season; Ronald Falk worked on the intricate macramé pieces in gold, inlaid with paste jewels, that would decorate the costumes for the production of Macbeth in the Opera Theatre later in the year.

Soldiers would lounge against the corridor wall chatting with convicts. Each night a diminutive, naked Jack Charles as Bennelong would emerge from his dressing room, run down the corridor with a grin and a wave at those gathered there and disappear into the lift that took us down to stage level. He had a cloud of black curls rather than the head of snow-white hair that is now so well known.

I took part in four of the plays presented by the Old Tote during the 1973 and ’74 seasons and toured to Melbourne with Williamson’s What if You Died Tomorrow. The company that started out in a converted tin shed on the campus of University of New South Wales in 1963 and was the training-ground of generations of NIDA students eventually closed down in November 1978. In December of that year, the Sydney Theatre Company was formed to take the Old Tote’s place as the resident Sydney Opera House drama company, and it has since spread to an extensive range of venues in the Wharf precinct.

I gave up professional acting in 1976 when the demands of that life became impossible to manage as a single parent with two small children. But my early experience and training as an actor did inspire my choice to write biography, enabling me to put myself in others’ shoes and see the world from their perspective. The view from the stage has become the view into the archives where I am alert, not to the mood of the audience but to the subtext of letters and the voices of my subjects. •